Как правильно пишется словосочетание «Прибалтийские государства»

Прибалти́йские госуда́рства

Прибалти́йские госуда́рства

Источник: Орфографический

академический ресурс «Академос» Института русского языка им. В.В. Виноградова РАН (словарная база

2020)

Делаем Карту слов лучше вместе

Привет! Меня зовут Лампобот, я компьютерная программа, которая помогает делать

Карту слов. Я отлично

умею считать, но пока плохо понимаю, как устроен ваш мир. Помоги мне разобраться!

Спасибо! Я стал чуточку лучше понимать мир эмоций.

Вопрос: смерд — это что-то нейтральное, положительное или отрицательное?

Ассоциации к слову «государство»

Синонимы к словосочетанию «прибалтийские государства»

Предложения со словосочетанием «Прибалтийские государства»

- Это были соединения, сформированные из дивизий армий прибалтийских государств.

- Западные державы оказывали помощь белогвардейским соединениям через посредство новых прибалтийских государств.

- Прибалтийские государства создали своим гражданам невыносимые условия жизни, а затем превратили бегство населения в панацею от всех социально-экономических трудностей; почему же они теперь вправе рассчитывать на возвращение эмигрантов, которых сами же своей политикой вытолкали за дверь?

- (все предложения)

Сочетаемость слова «государство»

- советское государство

российское государство

русское государство - государства мира

государство рабочих

государство людей - глава государства

управление государством

территория государства - государство возникает

государство существует

государство распалось - создать государство

управлять государством

стала независимым государством - (полная таблица сочетаемости)

Значение слова «государство»

-

ГОСУДА́РСТВО, -а, ср. Политическая организация общества во главе с правительством и его органами, с помощью которой господствующий класс осуществляет свою власть, обеспечивает охрану существующего порядка и подавление классовых противников, а также страна с такой политической организацией. Социалистическое государство. Буржуазное государство. (Малый академический словарь, МАС)

Все значения слова ГОСУДАРСТВО

Значение слова «прибалтийский»

-

1. относящийся к странам Балтии или к территории в районе побережья Балтийского моря (Викисловарь)

Все значения слова ПРИБАЛТИЙСКИЙ

Афоризмы русских писателей со словом «государство»

- Персидский ковер имен государств

Да сменится лучом человечества. - В том государстве, где писатели наслаждаются дарованною им свободою, имеют они долг возвысить громкий глас свой против злоупотреблений и предрассудков, вредящих отечеству.

- Из совокупности

Избытков скоростей,

Машин и жадности

Возникло государство. - (все афоризмы русских писателей)

Отправить комментарий

Дополнительно

«прибалтийские» — Фонетический и морфологический разбор слова, деление на слоги, подбор синонимов

Фонетический морфологический и лексический анализ слова «прибалтийские». Объяснение правил грамматики.

Онлайн словарь Soosle.ru поможет: фонетический и морфологический разобрать слово «прибалтийские» по составу, правильно делить на слоги по провилам русского языка, выделить части слова, поставить ударение, укажет значение, синонимы, антонимы и сочетаемость к слову «прибалтийские».

Содержимое:

- 1 Как перенести слово «прибалтийские»

- 2 Морфологический разбор слова «прибалтийские»

- 3 Разбор слова «прибалтийские» по составу

- 4 Синонимы слова «прибалтийские»

- 5 Предложения со словом «прибалтийские»

- 6 Сочетаемость слова «прибалтийские»

- 7 Значение слова «прибалтийские»

- 8 Как правильно пишется слово «прибалтийские»

- 9 Ассоциации к слову «прибалтийские»

Как перенести слово «прибалтийские»

при—балтийские

приба—лтийские

прибал—тийские

прибалтий—ские

прибалтийс—кие

Морфологический разбор слова «прибалтийские»

Часть речи:

Имя прилагательное (полное)

Грамматика:

часть речи: имя прилагательное (полное);

одушевлённость: неодушевлённое;

число: множественное;

падеж: именительный, винительный;

отвечает на вопрос: Какие?

Начальная форма:

прибалтийский

Разбор слова «прибалтийские» по составу

| при | приставка |

| балт | корень |

| ий | суффикс |

| ск | суффикс |

| ий | окончание |

прибалтийский

Синонимы слова «прибалтийские»

Предложения со словом «прибалтийские»

Ну и плюс ко всему практически откроем границу для поляков и жителей прибалтийских республик.

Юрий Иванович, Активная защита, 2012.

Однако для боевых вылетов непосредственно над линией фронта уж начинали использоваться и захваченные советские аэродромы, находившиеся на территории прибалтийских стран.

Михаил Зефиров, Цель – корабли. Противостояние Люфтваффе и советского Балтийского флота, 2008.

Он говорит с сильным прибалтийским акцентом, поэтому я с трудом понимал его немецкий.

Уильям Ширер, Берлинский дневник. Европа накануне Второй мировой войны глазами американского корреспондента.

Сочетаемость слова «прибалтийские»

1. прибалтийские республики

2. прибалтийские страны

3. прибалтийские государства

4. (полная таблица сочетаемости)

Значение слова «прибалтийские»

1. относящийся к странам Балтии или к территории в районе побережья Балтийского моря (Викисловарь)

Как правильно пишется слово «прибалтийские»

Правописание слова «прибалтийские»

Орфография слова «прибалтийские»

Правильно слово пишется:

Нумерация букв в слове

Номера букв в слове «прибалтийские» в прямом и обратном порядке:

Ассоциации к слову «прибалтийские»

-

Прибалтика

-

Фронт

-

Латвия

-

Эстония

-

Рига

-

Литва

-

Финляндия

-

Губерния

-

Пакт

-

Дивизия

-

Двина

-

Генерал-губернатор

-

Белоруссия

-

Акцент

-

Националист

-

Генерал-полковник

-

Полка

-

Округа

-

Директива

-

Присоединение

-

Ефрейтор

-

Янтарь

-

Эскадрилья

-

Республика

-

Пруссия

-

Славянин

-

Гвардия

-

Польша

-

Румыния

-

Псков

-

Группировка

-

Красноармеец

-

Дворянство

-

Округ

-

Армия

-

Взвод

-

Государство

-

Молдавия

-

Автоматчик

-

Оккупация

-

Швеция

-

Нато

-

Немец

-

Германия

-

Наступление

-

Плацдарм

-

Молотов

-

Бригада

-

Генштаб

-

Операция

-

Батальон

-

Прорыв

-

Белорусский

-

Гвардейский

-

Наступательный

-

Рижский

-

Эстонский

-

Стрелковый

-

Ленинградский

-

Витебский

-

Латвийский

-

Балтийский

-

Механизированный

-

Штурмовой

-

Ударный

-

Оборонительный

-

Истребительный

-

Карельский

-

Стратегический

-

Авиационный

-

Литовский

-

Скандинавский

-

Фронтовой

-

Брянский

-

Командующий

-

Одесский

-

Артиллерийский

-

Дальневосточный

-

Северо-западный

-

Воронежский

-

Танковый

-

Разведывательный

-

Псковской

-

Виленский

-

Пограничный

-

Приграничный

-

Отечественный

-

Дворянский

-

Самоходный

-

Антисоветский

-

Западный

-

Финский

-

Юго-западный

-

Украинский

-

Продвинуться

-

Расформировать

-

Воевать

-

Прорвать

-

Командовать

-

Округ

На букву П Со слова «прибалтийские»

Фраза «прибалтийские страны»

Фраза состоит из двух слов и 19 букв без пробелов.

- Синонимы к фразе

- Написание фразы наоборот

- Написание фразы в транслите

- Написание фразы шрифтом Брайля

- Передача фразы на азбуке Морзе

- Произношение фразы на дактильной азбуке

- Остальные фразы со слова «прибалтийские»

- Остальные фразы из 2 слов

Эмигрант правдиво о Латвии

Россия разорила порты прибалтийских сестриц

Почему прибалты ненавидят русских ?

Прибалтийские страны-прилипалы ищут, к кому бы еще присосаться (Уставший Оптимист)

Страны Прибалтики встречают свое столетие массовым вымиранием

Прибалтийские страны и Россия. Анатолий Вассерман.

Синонимы к фразе «прибалтийские страны»

Какие близкие по смыслу слова и фразы, а также похожие выражения существуют. Как можно написать по-другому или сказать другими словами.

Фразы

- + автономный край −

- + агрессивные устремления −

- + балканские страны −

- + безвизовый режим −

- + ближнее зарубежье −

- + братский народ −

- + великая держава −

- + военные блоки −

- + восточноевропейские страны −

- + государственная независимость −

- + дипломатическое признание −

- + естественный союзник −

- + западная страна −

- + западноевропейские страны −

- + иметь общую границу −

- + калининградская область −

- + коллективная безопасность −

- + малые страны −

- + оккупированная страна −

- + османская империя −

- + политическая интеграция −

- + правящие круги −

- + прибалтийские государства −

- + прибалтийские республики −

Ваш синоним добавлен!

Написание фразы «прибалтийские страны» наоборот

Как эта фраза пишется в обратной последовательности.

ынартс еиксйитлабирп 😀

Написание фразы «прибалтийские страны» в транслите

Как эта фраза пишется в транслитерации.

в армянской🇦🇲 պրիբալտիյսկիե ստրանը

в грузинской🇬🇪 პრიბალთისკიე სთრანი

в латинской🇬🇧 pribaltyskiye strany

Как эта фраза пишется в пьюникоде — Punycode, ACE-последовательность IDN

xn--80abnjcagig0blsk xn--80a0ahdf1d

Как эта фраза пишется в английской Qwerty-раскладке клавиатуры.

ghb,fknbqcrbtcnhfys

Написание фразы «прибалтийские страны» шрифтом Брайля

Как эта фраза пишется рельефно-точечным тактильным шрифтом.

⠏⠗⠊⠃⠁⠇⠞⠊⠯⠎⠅⠊⠑⠀⠎⠞⠗⠁⠝⠮

Передача фразы «прибалтийские страны» на азбуке Морзе

Как эта фраза передаётся на морзянке.

⋅ – – ⋅ ⋅ – ⋅ ⋅ ⋅ – ⋅ ⋅ ⋅ ⋅ – ⋅ – ⋅ ⋅ – ⋅ ⋅ ⋅ – – – ⋅ ⋅ ⋅ – ⋅ – ⋅ ⋅ ⋅ ⋅ ⋅ ⋅ – ⋅ – ⋅ ⋅ – – ⋅ – ⋅ – –

Произношение фразы «прибалтийские страны» на дактильной азбуке

Как эта фраза произносится на ручной азбуке глухонемых (но не на языке жестов).

Передача фразы «прибалтийские страны» семафорной азбукой

Как эта фраза передаётся флажковой сигнализацией.

Остальные фразы со слова «прибалтийские»

Какие ещё фразы начинаются с этого слова.

- прибалтийские бароны

- прибалтийские государства

- прибалтийские губернии

- прибалтийские земли

- прибалтийские народы

- прибалтийские националисты

- прибалтийские немцы

- прибалтийские племена

- прибалтийские провинции

- прибалтийские республики

- прибалтийские славяне

- прибалтийские территории

- прибалтийские финны

Ваша фраза добавлена!

Остальные фразы из 2 слов

Какие ещё фразы состоят из такого же количества слов.

- а вдобавок

- а вдруг

- а ведь

- а вот

- а если

- а ещё

- а именно

- а капелла

- а каторга

- а ну-ка

- а приятно

- а также

- а там

- а то

- аа говорит

- аа отвечает

- аа рассказывает

- ааронов жезл

- аароново благословение

- аароново согласие

- аб ово

- абажур лампы

- абазинская аристократия

- абазинская литература

Комментарии

04:08

Что значит фраза «прибалтийские страны»? Как это понять?..

Ответить

08:25

×

Здравствуйте!

У вас есть вопрос или вам нужна помощь?

Спасибо, ваш вопрос принят.

Ответ на него появится на сайте в ближайшее время.

А Б В Г Д Е Ё Ж З И Й К Л М Н О П Р С Т У Ф Х Ц Ч Ш Щ Ъ Ы Ь Э Ю Я

Транслит Пьюникод Шрифт Брайля Азбука Морзе Дактильная азбука Семафорная азбука

Палиндромы Сантана

Народный словарь великого и могучего живого великорусского языка.

Онлайн-словарь слов и выражений русского языка. Ассоциации к словам, синонимы слов, сочетаемость фраз. Морфологический разбор: склонение существительных и прилагательных, а также спряжение глаголов. Морфемный разбор по составу словоформ.

По всем вопросам просьба обращаться в письмошную.

Довольно часто из уст украинских, наших либеральных деятелей и СМИ вылетает, разрезая слух, словосочетание «страны Балтии». … Не изменилась ли норма русского языка? – возник у меня вопрос, други моя.

*

«…В этом нет ничего обидного. Равно как нет ничего обидного в «государствах Причерноморья» или «государствах Средиземноморья». В конце концов, такова норма русского языка. Наши эстонские соседи город Псков называют «Пихква» – можете посмотреть на любую эстонскую карту. Для русского человека это звучит немного странно, но такова норма эстонского языка. … традиционные филологические нормы надо уважать.»

В Литве, Латвии и Эстонии периодически разворачиваются дискуссии о том, как справедливо называть Прибалтийский регион. О лингвистических тонкостях и их смысле порталу RuBaltic.Ru рассказал президент Российской ассоциации прибалтийских исследований Николай МЕЖЕВИЧ.

– В странах Балтии периодически возникают дебаты на тему уместности употребления термина «Прибалтика» россиянами для обозначения Литвы, Латвии и Эстонии. На днях литовский философ Гинтаутас Мажейкис на страницах портала Delfi рассуждал, что «Прибалтика» – советский политический артефакт, симулякр. А правильно говорить «страны Балтии». Ваша Ассоциация как раз содержит слово «прибалтийских». Что Вы можете ответить господину Мажейкису?

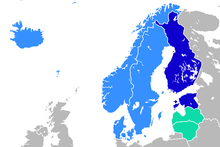

– Я бы посоветовал господину философу немного подняться над национальным восприятием терминологии и посмотреть, какие топонимы существуют в русском языке и являются для него традиционными. Все согласны, что омывающее Литву море называется Балтийским. Аналогично «средиземноморские страны» выходят к Средиземному морю, а «каспийские страны» омываются Каспием. А «балтийские страны» – Балтикой. Но балтийские страны – это не только Литва, Латвия и Эстония, но ещё и Польша, Германия, Дания, Швеция, Финляндия и Россия. Случаи Норвегии и Беларуси вызывают дискуссии: водосбор с Балтийского моря есть, но прямого выхода к Балтике нет. Поэтому пространство от России до Германии, учитывая формальное наличие выхода к морю, можно называть «балтийскими странами».

- Возникает вопрос, чем мерить степень «балтийскости» и откуда пошёл термин «страны Балтии».

Это понятие появилось после Первой мировой войны, и то далеко не сразу. Дело в том, что земли, населённые литовцами, в социокультурном смысле никогда не попадали в одну группу с остзейскими губерниями – будущими Эстонией и Латвией. Это были абсолютно разные региональные общности. Огромной проблемой, скажем, для МИД Великобритании была классификация дискуссии британских дипломатов и географов по этому поводу. Первоначально балтийскими странами считались Финляндия, Эстония и Латвия, но вовсе не Литва, которая вместе с Польшей рассматривалась как центральноевропейская страна. Но впоследствии, за время 20 лет первой независимости, входа и затем выхода из состава СССР, сформировалась единая концепция исторической общности, состоящей из трёх государств. Подчеркну, с точки зрения наших прибалтийских соседей, есть проблема: в СССР их страны были «республиками Прибалтики». Под республиками тогда подразумевалась не республиканская форма правления, а то, что они не были независимыми государствами.

- Я, мои коллеги и ученики в научных работах пишем «государства Прибалтики», обозначая их независимость.

В этом нет ничего обидного. Равно как нет ничего обидного в «государствах Причерноморья» или «государствах Средиземноморья». В конце концов, такова норма русского языка. Наши эстонские соседи город Псков называют «Пихква» – можете посмотреть на любую эстонскую карту. Для русского человека это звучит немного странно, но такова норма эстонского языка. Эстонцы, тем не менее, просят нас писать «Таллин» с двумя «н», на что мы опять отвечаем, что существуют устойчивые правила русского языка. Это всё напоминает дискуссии вокруг того, как писать: поехать «на Украину» или «в Украину». Ничего политического здесь нет. Есть только языковые нормы. Так что давайте нам в нашей стране разрешим разговаривать на своём языке и называть страны так, как мы называем. Мы же Китай называем Китаем, хотя ни одна страна больше так не делает.

Литовский философ Гинтаутас Мажейкис

– Мажейкис и его сторонники утверждают, что дело не только в географии и лингвистике. По их мнению, говоря «Прибалтика», люди реализуют имперское мышление, оставшееся от Советского Союза.

– Могу только посоветовать то, что советуют обычно врачам: исцели себя сам. Для начала Литве следует избавиться от имперского мышления, ото всех псевдовоспоминаний о Великом княжестве Литовском – эти воспоминания очень мешают налаживать отношения с Беларусью, к примеру, – а потом смотреть на окружающих.

- Правильное название в политическом смысле звучит так: «государства Прибалтики». Подчёркиваю: «государства»! Таким образом, мы чётко указываем соседям, что у нас нет ни малейшего сомнения в их государственности.

В русском языке вообще вплоть до 1991 года формулировка «страны Балтии» не употреблялась. Её просто не было. Со стороны литовских деятелей в данном случае идёт попытка навязать свой языковой стандарт чужой стране. Во-первых, это хамство. Во-вторых, у них ничего не получится. Никто, при этом, не говорит о том, что не уважает литовскую государственность. Хотелось бы, чтобы уважение к своей государственности сочеталось с уважением к государственности соседа. Пока же мы видим, что сознательное искажение фактов о прошлых и настоящих отношениях между Россией и народами Прибалтики – государственная идеология действующих политических элит этих стран.

Книги «История Литвы»

– История знает прецеденты, когда страны, желая избавиться от негативного, по их мнению, прошлого, официально просили весь мир называть их иначе. Так, Берег Слоновой Кости стал Кот-д’Ивуар. Вам и Вашим коллегам сложно пойти навстречу Литве?

– Это не самая большая проблема и не самый масштабный спор. Если наши соседи захотят переименоваться, это воля литовского народа. Но не стоит лезть со своей политической волей в чужой политический огород. Об этом и идёт речь. В своё время я проанализировал, как Литву, Латвию и Эстонию называли руководители российского государства. На уровне президента и правительства в целом используются оба названия: «Прибалтика» и «страны Балтии».

- В частности, президент Путин примерно до середины 2000х употреблял вариант «страны Балтии». Доктринальные документы МИД РФ в начале 90х тоже использовали термин «страны Балтии», а потом перешли на термин «страны Прибалтики». Произошло осознание того, что традиционные филологические нормы надо уважать.

Для сравнения: я много дискутировал с коллегами из Белоруссии. С большинством мы пришли к выводу, что не столь важно, как говорить и писать, «Белоруссия» или «Беларусь». Важнее, чтобы развивались политические и экономические отношения между двумя странами. Развивались в духе добрососедства и взаимопонимания.

Обсуждение в литовском Сейме

– Аналогично Мажейкис выступает против термина «постсоветское пространство», называя его бессодержательным. Он объясняет, что постсоветскими называли страны, переживающие транзитарный, «переходный» период от социализма к рынку и демократии. Поскольку Литва переход завершила, её нельзя включать в постсоветское поле.

– Есть русская поговорка: «Чует кошка, чьё мясо съела». Несмотря на все усилия по преодолению «постсоветскости», ни Эстония, ни Латвия, ни Литва, ни страны Восточной Европы из этой «постсоветскости» не вышли. Многие выдающиеся учёные, часть политиков, эксперты, наблюдая за происходящим, говорят: наследие социалистической эпохи оказалось гораздо прочнее, чем кто-либо думал. Об этом свидетельствуют многие вещи.

- Например, когда периодически возникают коррупционные скандалы, идёт война с памятниками – эстонские политологи придумали интересный термин «seemukapitalism», то есть «капитализм братанов».

Все знакомые проблемы, от тяготения к авторитаризму до езды пьяными на лошади или за рулём, были в досоветскую и советскую эпоху и спокойно сохранились в Прибалтике. Одним из признаков дремучей постсоветскости служит объяснение всех своих бед тем, что страна находилась в составе СССР. Когда литовский, латвийский или эстонский министр выступает и говорит, что в плохом состоянии больниц или дорог виноваты Сталин с Хрущёвым и Горбачёвым, – это и есть, если угодно, первобытная постсоветскость. Когда утверждают, что в том, что за 25 лет не смогли навести в своей стране порядок, виноваты все вокруг, кроме них. В этом плане проще убирать статуи с мостов, разрушать памятники советским солдатам и вести разговоры о терминологии. Заметьте, в Германии никто на Трептов-парк не покушается и подобные беседы не ведёт.

Вообще же установление контроля над воспоминанием и забвением является одной из постоянных забот классов, групп и индивидов, которые доминировали в исторических обществах. Это сказал не я, а написал французский историк и социолог Жак Ле Гофф, классик, извините.

– Политики в странах Балтии в последнее время обвиняют в рецидивах советского стиля не только Россию, но и друг друга. Например, это особо ярко проявляется в спорах вокруг литовского Трудового кодекса, конфликтах разных партий между собой. О чём это говорит?

– Для католического священника в период Реформации не было ничего хуже, чем назвать своего соседа приверженцем ереси Лютера или Кальвина. Это было хуже каннибализма, отцеубийства, за пределами добра и зла! На постсоветском пространстве похожий синдром часто встречается, когда человека обвиняют в советском образе мысли или действий. Справедливости ради, это встречается не только в Прибалтике, но и в Центральной и Восточной Европе и на Балканах от Польши до Албании.

Rubaltic.ru

«Baltics» redirects here. For other uses, see Baltic.

This article is about a geopolitical grouping of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania. For the region in Northern Europe they are situated in, see Baltic region. For a region in southern Europe, see Balkans.

| Baltic states | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Area | 175,228 sq. km |

| Countries | |

| Time zones |

|

The Baltic states[a] or the Baltic countries is a geopolitical term, which currently is used to group three countries: Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania. All three countries are members of NATO, the European Union, the Eurozone, and the OECD. The three sovereign states on the eastern coast of the Baltic Sea are sometimes referred to as the «Baltic nations», less often and in historical circumstances also as the «Baltic republics», the «Baltic lands», or simply the Baltics.

All three Baltic countries are classified as high-income economies by the World Bank and maintain a very high Human Development Index.[1] The three governments engage in intergovernmental and parliamentary cooperation. There is also frequent cooperation in foreign and security policy, defence, energy, and transportation.[2]

The term «Baltic states» («countries», «nations», or similar) cannot be used unambiguously in the context of cultural areas, national identity, or language. While the majority of the population both in Latvia and Lithuania are indeed Baltic peoples (Latvians and Lithuanians), the majority in Estonia (Estonians) are culturally and linguistically Finnic.[2]

History[edit]

Summary[edit]

After the First World War the term «Baltic states» came to refer to countries by the Baltic Sea that had gained independence from the Russian Empire. The term includes Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania, and originally also included Finland, which later became grouped among the Nordic countries.[3]

The areas of what are now the independent Baltic countries have seen different regional and imperial affiliations during their existence. The greater part of the three modern states’ territory was for the first time included in the same political entity when the Russian Empire expanded in the 18th century. Estonia and northern part of Latvia were ceded by Sweden, and incorporated into the Russian Empire at the end of the Great Northern War in 1721, while most of the territory of what is now Lithuania came under Russian rule after the Third Partition of Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth in 1795. Large parts of the Baltic countries were controlled by the Russian Empire until the final stages of World War I in 1918, when Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania gained their sovereignty. The three countries were independent until the outbreak of World War II. In 1940, all three countries were invaded, occupied and annexed by the Stalinist Soviet Union. 1941 saw the invasion and occupation of Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia by Nazi Germany, before the Red Army re-conquered the territory in 1944–1945, after which the Soviet Union maintained control over the three countries until 1991. Soviet rule ended in the Baltic countries in 1989–1991, as the newly elected parliaments of the three nations declared the Soviet occupation illegal, culminating with the full restoration of the independence of the three countries in August 1991.

The first period of independence, 1918–1940[edit]

As World War I came to a close, Lithuania declared independence and Latvia formed a provisional government. Estonia had already obtained autonomy from tsarist Russia in 1917, and declared independence in February 1918, but was subsequently occupied by the German Empire until November 1918. Estonia fought a successful war of independence against Soviet Russia in 1918–1920. Latvia and Lithuania followed a similar process, until the completion of the Latvian War of Independence and Lithuanian Wars of Independence in 1920.

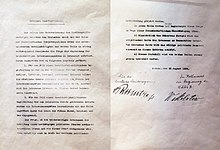

According to the 1939 Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact «the Baltic States (Finland, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania)» were divided into German and Soviet «spheres of influence» (German copy)

During the interwar period these countries were sometimes referred to as limitrophe states between the two World Wars, from the French, indicating their collectively forming a rim along Bolshevik Russia’s, later the Soviet Union’s, western border. They were also part of what Georges Clemenceau considered a strategic cordon sanitaire, the entire territory from Finland in the north to Romania in the south, standing between Western Europe and potential Bolshevik territorial ambitions.[4][5]

All three Baltic countries experienced a period of authoritarian rule by a head of state who had come to power after a bloodless coup: Antanas Smetona in Lithuania (1926–1940), Kārlis Ulmanis in Latvia (1934–1940), and Konstantin Päts during the «era of silence» (1934–1938) in Estonia, respectively. Some note that the events in Lithuania differed from the other two countries, with Smetona having different motivations as well as securing power 8 years before any such events in Latvia or Estonia took place. Despite considerable political turmoil in Finland no such events took place there. Finland did however get embroiled in a bloody civil war, something that did not happen in the Baltics.[6] Some controversy surrounds the Baltic authoritarian régimes – due to the general stability and rapid economic growth of the period (even if brief), some commenters avoid the label «authoritarian»; others, however, condemn such an «apologetic» attitude, for example in later assessments of Kārlis Ulmanis.

Soviet and German occupations, 1940–1991[edit]

Geopolitical status in Northern Europe in November 1939[7][8]

Neutral countries

Germany and annexed countries

Soviet Union and annexed countries

Neutral countries with military bases established by Soviet Union in October 1939

In accordance with a secret protocol within the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact of 1939 that divided Europe into German and Soviet spheres of influence, the Soviet Army invaded eastern Poland in September 1939, and the Stalinist Soviet government coerced Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania into «mutual assistance treaties» which granted USSR the right to establish military bases in these countries. In June 1940, the Red Army occupied all of the territory of Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania, and installed new, pro-Soviet puppet governments. In all three countries simultaneously, rigged elections (in which only pro-Stalinist candidates were allowed to run) were staged in July 1940, the newly assembled «parliaments» in each of the three countries then unanimously applied to join the Soviet Union, and in August 1940 were incorporated into the USSR as the Estonian SSR, Latvian SSR, and Lithuanian SSR.

Repressions, executions and mass deportations followed after that in the Baltics.[9][10] The Soviet Union attempted to Sovietize its occupied territories, by means such as deportations and instituting the Russian language as the only working language. Between 1940 and 1953, the Soviet government deported more than 200,000 people from the Baltics to remote locations in the Soviet Union. In addition, at least 75,000 were sent to Gulags. About 10% of the adult Baltic population were deported or sent to labor camps.[11] (See June deportation, Soviet deportations from Estonia, Sovietization of the Baltic states)

The Soviet occupation of the Baltic countries was interrupted by Nazi German invasion of the region in 1941. Initially, many Estonians, Latvians, and Lithuanians considered the German army as liberators, while having hoped for the restoration of each of the three countries’ independence, but instead the Nazi German invaders established a civil administration, known as the Reichskommissariat Ostland.[citation needed] During the occupation the Nazi authorities carried out ghettoisations and mass killings of the Jewish populations in Lithuania and Latvia.[12] Over 190,000 Lithuanian Jews, nearly 95% of Lithuania’s pre-war Jewish community, and 66,000 Latvian Jews were murdered. The German occupation lasted until late 1944 (in Courland, until early 1945), when the countries were reoccupied by the Red Army and Soviet rule was re-established, with the passive agreement of the United States and Britain (see Yalta Conference and Potsdam Agreement).

The forced collectivisation of agriculture began in 1947, and was completed after the mass deportation in March 1949 (see Operation Priboi). Private farms were confiscated, and farmers were made to join the collective farms. In all three countries, Baltic partisans, known colloquially as the Forest Brothers, Latvian national partisans, and Lithuanian partisans, waged unsuccessful guerrilla warfare against the Soviet occupation for the next eight years in a bid to regain their nations’ independence. The armed resistance of the anti-Soviet partisans lasted up to 1953. Although the armed resistance was defeated, the population remained anti-Soviet.

Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia were considered to be under Soviet occupation by the United States, the United Kingdom,[13] Canada, NATO, and many other countries and international organizations.[14] During the Cold War, Lithuania and Latvia maintained legations in Washington DC, while Estonia had a mission in New York City. Each was staffed initially by diplomats from the last governments before USSR occupation.[15]

Restoration of independence[edit]

In the late 1980s, a massive campaign of civil resistance against Soviet rule, known as the Singing revolution, began. On 23 August 1989, the Baltic Way, a two-million-strong human chain, stretched for 600 km from Tallinn to Vilnius. In the wake of this campaign, Gorbachev’s government had privately concluded that the departure of the Baltic republics had become «inevitable».[16] This process contributed to the dissolution of the Soviet Union, setting a precedent for the other Soviet republics to secede from the USSR. The Soviet Union recognized the independence of three Baltic states on 6 September 1991. Troops were withdrawn from the region (starting from Lithuania) from August 1993. The last Russian troops were withdrawn from there in August 1994.[17] Skrunda-1, the last Russian military radar in the Baltics, officially suspended operations in August 1998.[18]

21st century[edit]

All three are today liberal democracies, with unicameral parliaments elected by popular vote for four-year terms: Riigikogu in Estonia, Saeima in Latvia and Seimas in Lithuania. In Latvia and Estonia, the president is elected by parliament, while Lithuania has a semi-presidential system whereby the president is elected by popular vote. All are part of the European Union (EU) and members of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO).

Each of the three countries has declared itself to be the restoration of the sovereign nation that had existed from 1918 to 1940, emphasizing their contention that Soviet domination over the Baltic states during the Cold War period had been an illegal occupation and annexation.

The same legal interpretation is shared by the United States, the United Kingdom, and most other Western democracies,[citation needed] who held the forcible incorporation of Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania into the Soviet Union to be illegal. At least formally, most Western democracies never considered the three Baltic states to be constituent parts of the Soviet Union. Australia was a brief exception to this support of Baltic independence: in 1974, the Labor government of Australia did recognize Soviet dominion, but this decision was reversed by the next Australian Parliament.[19] Other exceptions included Sweden, which was the first Western country, and one of the very few to ever do so, to recognize the incorporation of the Baltic states into the Soviet Union as lawful.[20]

After the Baltic states had restored their independence, integration with Western Europe became a major strategic goal. In 2002, the Baltic governments applied to join the European Union and become members of NATO. All three became NATO members on 29 March 2004, and joined the EU on 1 May 2004.

Regional cooperation[edit]

During the Baltic struggle for independence 1989–1992, a personal friendship developed between the (at that time unrecognized) Baltic ministers of foreign affairs and the Nordic ministers of foreign affairs. This friendship led to the creation of the Council of the Baltic Sea States in 1992, and the EuroFaculty in 1993.[21]

Between 1994 and 2004, the BAFTA free trade agreement was established to help prepare the countries for their accession to the EU, rather than out of the Baltic states’ desire to trade among themselves. The Baltic countries were more interested in gaining access to the rest of the European market.

Currently, the governments of the Baltic states cooperate in multiple ways, including cooperation among presidents, parliament speakers, heads of government, and foreign ministers. On 8 November 1991, the Baltic Assembly, which includes 15 to 20 MPs from each parliament, was established to facilitate inter-parliamentary cooperation. The Baltic Council of Ministers was established on 13 June 1994 to facilitate intergovernmental cooperation. Since 2003, there is coordination between the two organizations.[22]

Compared with other regional groupings in Europe, such as the Nordic Council or Visegrád Group, Baltic cooperation is rather limited. All three countries are also members of the New Hanseatic League, an informal group of northern EU states formed to advocate a common fiscal position.

Economies[edit]

Economically, parallel with political changes and a transition to democracy – as a rule of law states – the nations’ previous command economies were transformed via the legislation into market economies, and set up or renewed the major macroeconomic factors: budgetary rules, national audit, national currency and central bank. Generally, they shortly encountered the following problems: high inflation, high unemployment, low economic growth and high government debt. The inflation rate, in the examined area, relatively quickly dropped to below 5% by 2000. Meanwhile, these economies were stabilised, and in 2004 all of them joined the European Union. New macroeconomic requirements have arisen for them; the Maastricht criteria became obligatory and later the Stability and Growth Pact set stricter rules through national legislation by implementing the regulations and directives of the Sixpack, because the financial crisis was a shocking milestone.[23]

All three countries are member states of the European Union, and the Eurozone. They are classified as high-income economies by the World Bank and maintain high Human Development Index. Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania are also members of the OECD.[1]

Estonia adopted the euro currency in January 2011, Latvia in January 2014, and Lithuania in January 2015.

Energy security of Baltic states[edit]

Usually the concept of energy security is related to the uninterruptible supply, sufficient energy storage, advanced technological development of energy sector and environmental regulations.[24] Other studies add other indicators to this list: diversification of energy suppliers, energy import dependence and vulnerability of political system.[25]

Even now being a part of the European Union, Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania are still considered as the most vulnerable EU member states in the energy sphere.[26] Due to their Soviet past, Baltic states have several gas pipelines on their territories coming from Russia. Moreover, several routes of oil delivery also have been sustained from Soviet times: These are ports in Ventspils, Butinge and Tallinn.[27] Therefore, Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania play a significant role not only in consuming, but also in distribution of Russian energy fuels extracting transaction fees.[27] So, the overall EU dependence on the Russia’s energy supplies from the one hand and the need of Baltic states to import energy fuels from their closer hydrocarbon-rich neighbor creates a tension that could jeopardize the energy security of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania.[27]

As a part of the EU from 2004, Baltic states must comply with the EU’s regulations in energy, environmental and security spheres. One of the most important documents that the EU applied to improve the energy security stance of the Baltic states are European Union climate and energy package, including the Climate and Energy Strategy 2020, that aims to reduce the greenhouse emissions to 20%, increase the energy production from renewables for 20% in overall share and 20% energy efficiency development.[28]

The calculations take into account not only economic, but also technological and energy-related factors: Energy and carbon intensity of transport and households, trade balance of total energy, energy import dependency, diversification of energy mix, etc.[24] It was stated that from 2008, Baltic states experiences a positive change in their energy security score. They diversified their oil import suppliers due to shutdown of Druzhba gas pipeline in 2006 and increased the share of renewable sources in total energy production with the help of the EU policies.[24]

Estonia usually was the best performing country in terms of energy security, but new assessment shows that even though Estonia has the highest share of renewables in the energy production, its energy economy has been still characterized by high rates of carbon intensity. Lithuania, in contrast, achieved the best results on carbon intensity of economy but its energy dependence level is still very high. Latvia performed the best according to all indicators. Especially, the high share of renewables were introduced to the energy production of Latvia, that can be explained by the state’s geographical location and favorable natural conditions.[24]

Possible threats to energy security include, firstly, a major risk of energy supply disruption. Even if there are several electricity interconnectors that connect the area with electricity-rich states (Estonia-Finland interconnector, Lithuania-Poland interconnector, Lithuania-Sweden interconnector), the pipeline supply of natural gas and tanker supply of oil are unreliable without modernization of energy infrastructure.[26] Secondly, the dependence on single supplier – Russia – is not healthy both for economics and politics.[29] As it was in 2009 during the Russian-Ukrainian gas dispute, when states of Eastern Europe were deprived from access to the natural gas deliveries, the reoccurrence of the situation may again lead to economic, political and social crisis. Therefore, the diversification of suppliers is needed.[26] Finally, the low technological enhancement results in slow adaptation of new technologies, such as construction and use of renewable sources of energy. This also poses a threat to energy security of the Baltic states, because slows down the renewable energy consumption and lead to low rates of energy efficiency.[26]

Culture[edit]

Ethnic groups[edit]

Estonians are Finnic people, together with the nearby Finns. The Latvians and Lithuanians, linguistically and culturally related to each other, are Baltic Indo-European people. In Latvia exists a small community of Finnic people related to the Estonians, composed of only 250 people, known as Livonians, and they live in the so-called Livonian Coast. The peoples in the Baltic states have together inhabited the eastern coast of the Baltic Sea for millennia, although not always peacefully in ancient times, over which period their populations, Estonian, Latvian, and Lithuanian, have remained remarkably stable within the approximate territorial boundaries of the current Baltic states. While separate peoples with their own customs and traditions, historical factors have introduced cultural similarities in and differences within them.

The populations of each Baltic country belong to several Christian denominations, a reflection of historical circumstances. Both Western and Eastern Christianity had been introduced by the end of the first millennium. The current divide between Lutheranism to the north and Catholicism to the south is the remnant of Swedish and Polish hegemony, respectively, with Orthodox Christianity remaining the dominant religion among Russian and other East Slavic minorities.

The Baltic states have historically been in many different spheres of influence, from Danish over Swedish and Polish–Lithuanian, to German (Hansa and Holy Roman Empire), and before independence in the Russian sphere of influence.

The Baltic states are inhabited by several ethnic minorities: in Latvia: 33.0% (including 25.4% Russian, 3.3% Belarusian, 2.2% Ukrainian, and 2.1% Polish),[30] in Estonia: 27.6%[31] and in Lithuania: 12.2% (including 5.6% Polish and 4.5% Russian).[32]

The Soviet Union conducted a policy of Russification by encouraging Russians and other Russian-speaking ethnic groups of the Soviet Union to settle in the Baltics. Today, ethnic Russian immigrants from the former Soviet Union and their descendants make up a sizable particularly in Latvia (about one-quarter of the total population and close to one-half in the capital Riga) and Estonia (nearly one-quarter of the total population).

Because the three countries had been independent nations prior to their occupation by the Soviet Union, there was a strong feeling of national identity (often labeled «bourgeois nationalism» by the Communist Party) and popular resentment towards the imposed Soviet rule in the three countries, in combination with Soviet cultural policy, which employed superficial multiculturalism (in order for the Soviet Union to appear as a multinational union based on the free will of its peoples) in limits allowed by the communist «internationalist» (but in effect pro-Russification) ideology and under tight control of the Communist Party (those of the Baltic nationals who crossed the line were called «bourgeois nationalists» and repressed). This let Estonians, Latvians and Lithuanians preserve a high degree of Europe-oriented national identity.[33] In Soviet times this made them appear as the «West» of the Soviet Union in the cultural and political sense, thus as close to emigration a Russian could get without leaving the USSR.

Languages[edit]

The languages of the three Baltic peoples belong to two distinct language families. The Latvian and Lithuanian languages belong to the Indo-European language family and are the only extant (widely recognized) members of the Baltic language group (or more specifically, Eastern Baltic subgroup of Baltic). Latgalian and Samogitian are considered either separate languages or dialects of Latvian and Lithuanian, respectively.

The Estonian language (including its divergent Võro and Seto dialects) is a Finnic language, together with neighboring Finland’s Finnish language. It is also related to the now near-extinct Livonian language spoken as a second language by a few dozen people in Latvia.

Apart from the indigenous languages, German was the dominant language in Estonia and Latvia in academics, professional life, and upper society from the 13th century until World War I. Polish served a similar function in Lithuania. Numerous Swedish loanwords have made it into the Estonian language; it was under the Swedish rule that schools were established and education propagated in the 17th century. Swedish remains spoken in Estonia, particularly the Estonian Swedish dialect of the Estonian Swedes of northern Estonia and the islands (though many fled to Sweden as the USSR invaded and re-occupied Estonia in 1944). There is also significant proficiency in Finnish in Estonia owing to its linguistic relationship with Estonian and also widespread exposure to Finnish broadcasts during the Soviet era.

Russian was the most commonly studied foreign language at all levels of schooling during the period of Soviet rule in 1944–1991. Despite schooling available and administration conducted in local languages, Russian-speaking settlers were neither encouraged nor motivated to learn the official local languages, so knowledge of some Russian became a practical necessity in daily life in Russian-dominated urban areas. Even to this day, most of the three countries’ adult population can understand and speak some Russian, especially so the elderly people who went to school during the Soviet rule.

Since the decline of Russian influence and integration into the European Union economy, English has become the most popular second language in the Baltic states. Although Russian is more widely spoken among older people the vast majority of young people are learning English instead with as many as 80 percent of young Lithuanians professing English proficiency, and similar trends in the other Baltic states.[34][35]

Baltic Romani is spoken by the Roma.

Etymology of the word Baltic[edit]

The Baltic Way was a mass anti-Soviet demonstration in 1989 where ca 25% of the total population of the Baltic countries participated

The term Baltic stems from the name of the Baltic Sea – a hydronym dating back to at least 3rd century B.C. (when Erastothenes mentioned Baltia in an Ancient Greek text) and possibly earlier.[36] There are several theories about its origin, most of which trace it to the reconstructed Proto-Indo-European root *bhel[37] meaning ‘white, fair’. This meaning is retained in the two modern Baltic languages, where baltas in Lithuanian and balts in Latvian mean ‘white’.[38] However, the modern names of the region and the sea that originate from this root, were not used in either of the two languages prior to the 19th century.[39][needs update]

Since the Middle Ages, the Baltic Sea has appeared on maps in Germanic languages as the equivalent of ‘East Sea’: German: Ostsee, Danish: Østersøen, Dutch: Oostzee, Swedish: Östersjön, etc. Indeed, the Baltic Sea lies mostly to the east of Germany, Denmark, Norway, and Sweden. The term was also used historically to refer to Baltic Dominions of the Swedish Empire (Swedish: Östersjöprovinserna) and, subsequently, the Baltic governorates of the Russian Empire (Russian: Остзейские губернии, romanized: Ostzejskie gubernii).[39] Terms related to modern name Baltic appear in ancient texts, but had fallen into disuse until reappearing as the adjective Baltisch in German, from which it was adopted in other languages.[40] During the 19th century, Baltic started to supersede Ostsee as the name for the region. Officially, its Russian equivalent Прибалтийский (Pribaltiyskiy) was first used in 1859.[39] This change was a result of the Baltic German elite adopting terms derived from Baltisch to refer to themselves.[40][41]

The term Baltic countries (or lands, or states) was, until the early 20th century, used in the context of countries neighbouring the Baltic Sea: Sweden and Denmark, sometimes also Germany and the Russian Empire. With the advent of Foreningen Norden (the Nordic Associations), the term was no longer used for Sweden and Denmark.[42][43] After World War I, the new sovereign states that emerged on the east coast of the Baltic Sea – Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, and Finland – became known as the Baltic states.[40] Since World War II the term has typically been used to group the three countries Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania.

Geography[edit]

Nature[edit]

-

Forests cover over half the landmass of Estonia

-

-

View from the Bilioniai forthill in Lithuania

Current leaders[edit]

General statistics[edit]

All three unitary republics, which simultaneously joined the European Union on 1 May 2004, share EET/EEST time zone schedules and the euro currency.

| Estonia | Latvia | Lithuania | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coat of arms |

|

|

|

— |

| Flag | — | |||

| Capital | Tallinn | Riga | Vilnius | — |

| Independence |

|

|

|

— |

| Political system | Parliamentary republic | Parliamentary republic | Semi-presidential republic | — |

| Parliament | Riigikogu | Saeima | Seimas | — |

| Current President | Alar Karis | Egils Levits | Gitanas Nausėda | — |

| Population (2022) | 1,331,796[45] | 1,875,757[46] | 2,830,097[47] | 6,037,650 |

| Area | 45,339 km2 = 17,505 sq mi | 64,589 km2 = 24,938 sq mi | 65,300 km2 = 25,212 sq mi | 175,228 km2 = 67,656 sq mi |

| Density | 30.9/km2 = 80/sq mi | 29/km2 = 76/sq mi | 43/km2 = 110/sq mi | 34/km2 = 88/sq mi |

| Water area % | 4.56% | 1.5% | 1.35% | 2.47% |

| GDP (nominal) total (2022)[48] | $37.202 billion | $40.830 billion | $69.780 billion | $147.812 billion |

| GDP (nominal) per capita (2022)[48] | $27,971 | $23,489 | $25,015 | $25,822 |

| Military budget (2022) | €748 million[49] | €758 million[50] | €1.5 billion[51] | €3.0 billion |

| Gini Index (2020)[52] | 30.5 | 34.5 | 35.1 | — |

| HDI (2019)[53] | 0.882 (Very High) | 0.854 (Very High) | 0.869 (Very High) | — |

| Internet TLD | .ee | .lv | .lt | — |

| Calling code | +372 | +371 | +370 | — |

See also[edit]

- Baltia

- Baltic Entente

- Baltic Finnic peoples

- Baltic Free Trade Area

- Baltic Germans

- Baltic governorates

- Baltic region

- Baltic Tiger

- Baltic Way

- Balto-Finnic languages

- Baltoscandia

- List of cities in the Baltic states by population

- Nordic-Baltic Eight

- Nordic countries

- Nordic Estonia

- Occupation of the Baltic states

- Russians in Estonia

- Russians in Latvia

- Russians in Lithuania

- United Baltic Duchy

- Soviet deportation from the Baltics in 1941

- Soviet deportation from the Baltics in 1949

- Soviet deportations from Estonia

- Soviet deportations from Latvia

- Soviet deportations from Lithuania

- German occupation of Estonia during World War II

- German occupation of Latvia during World War II

- German occupation of Lithuania during World War II

Notes[edit]

- ^ Lithuanian: Baltijos valstybės, Latvian: Baltijas valstis, Estonian: Balti riigid

References[edit]

- ^ a b «Colombia and Lithuania join the OECD». France 24. 30 May 2018.

- ^ a b Republic of Estonia. «Baltic Cooperation». Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Archived from the original on 6 May 2017. Retrieved 28 May 2018.

- ^ Maude, George (2010). Aspects of the Governing of the Finns. Peter Lang. ISBN 978-1-4331-0713-9.

- ^ Smele, John (1996). Civil war in Siberia: the anti-Bolshevik government of Admiral Kolchak, 1918–1920. London: Cambridge University Press. p. 305.

- ^ Calvo, Carlos (2009). Dictionnaire Manuel de Diplomatie et de Droit International Public et Privé. The Lawbook Exchange, Ltd. p. 246. ISBN 9781584779490.

- ^ «Why did Finland remain a democracy between the two World Wars, whereas the Baltic States developed authoritarian regimes?». January 2004.

as [Lithuania] is a distinct case from the other two Baltic countries. Not only was an authoritarian regime set up in 1926, eight years before those of Estonia and Latvia, but it was also formed not to counter a threat from the right, but through a military coup d’etat against a leftist government. (…) The hostility between socialists and non-socialists in Finland had been amplified by a bloody civil war

- ^ Kilin, Juri; Raunio, Ari (2007). Talvisodan taisteluja [Winter War Battles] (in Finnish). Karttakeskus. p. 10. ISBN 978-951-593-068-2.

- ^ Hough, William J.H. (10 September 2019). «The Annexation of the Baltic States and Its Effect on the Development of Law Prohibiting Forcible Seizure of Territory». DigitalCommons@NYLS.

- ^ «These Names Accuse—Nominal List of Latvians Deported to Soviet Russia». latvians.com. Archived from the original on 8 February 2012. Retrieved 28 May 2018.

- ^ Kangilaski, Jaak; Salo, Vello; Komisjon, Okupatsioonide Repressiivpoliitika Uurimise Riiklik (2005). The white book: losses inflicted on the Estonian nation by occupation regimes, 1940–1991. Estonian Encyclopaedia Publishers. ISBN 9789985701959.

- ^ «Communism and Crimes against Humanity in the Baltic states». 13 April 1999. Archived from the original on 20 July 2011. Retrieved 27 May 2018.

- ^ «Murder of the Jews of the Baltic States». Yad Vashem.

- ^ «Country Profiles: Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania». Foreign & Commonwealth Office – Government of the United Kingdom. Archived from the original on 31 July 2003. Retrieved 28 May 2018.

- ^ «U.S.-Baltic Relations: Celebrating 85 Years of Friendship». U.S. Department of State. 14 June 2007. Retrieved 27 May 2018.

- ^ Norman Kempster, Annexed Baltic States : Envoys Hold On to Lonely U.S. Postings Archived 19 August 2016 at the Wayback Machine Los Angeles Times, 31 October 1988. Retrieved 11 July 2016.

- ^ Beissinger, Mark R. (2009). «The intersection of Ethnic Nationalism and People Power Tactics in the Baltic States». In Adam Roberts; Timothy Garton Ash (eds.). Civil resistance and power politics: the experience of non-violent action from Gandhi to the present. Oxford & New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 231–246. ISBN 978-0-19-955201-6.

- ^ Pike, John. «Baltic Military District». Archived from the original on 8 November 2017. Retrieved 28 May 2018.

- ^ «SKRUNDA SHUTS DOWN. – Jamestown». Jamestown. 1 September 1993. Archived from the original on 28 May 2018. Retrieved 19 June 2013.

- ^ «The Latvians in Sydney». Sydney Journal. 1. March 2008. ISSN 1835-0151. Archived from the original on 19 October 2017. Retrieved 28 May 2018.

- ^ Kuldkepp, Mart. «Swedish political attitudes towards Baltic independence in the short twentieth century». Ajalooline Ajakiri. The Estonian Historical Journal (3/4). ISSN 2228-3897.

- ^ N., Kristensen, Gustav (2010). Born into a Dream : Eurofaculty and the Council of the Baltic Sea States. Berlin: BWV Berliner Wissenschafts-Verlag. ISBN 978-3-8305-2548-6. OCLC 721194688.

- ^ «Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Latvia: Co-operation among the Baltic States». 4 December 2008. Archived from the original on 4 December 2008. Retrieved 28 May 2018.

- ^ Vértesy, László (2018). «Macroeconomic Legal Trends in the EU11 Countries» (PDF). Public Governance, Administration and Finances Law Review. 3 (1): 94–108. doi:10.53116/pgaflr.2018.1.9. S2CID 219380180.

- ^ a b c d Zeng, Shouzhen; Streimikiene, Dalia; Baležentis, Tomas (September 2017). «Review of and comparative assessment of energy security in Baltic States». Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews. 76: 185–192. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2017.03.037. ISSN 1364-0321.

- ^ Kisel, Einari; Hamburg, Arvi; Härm, Mihkel; Leppiman, Ando; Ots, Märt (August 2016). «Concept for Energy Security Matrix». Energy Policy. 95: 1–9. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2016.04.034.

- ^ a b c d Molis, Arūnas (September 2011). «Building methodology, assessing the risks: the case of energy security in the Baltic States». Baltic Journal of Economics. 11 (2): 59–80. doi:10.1080/1406099x.2011.10840501. ISSN 1406-099X.

- ^ a b c Mauring, Liina (2006). «The Effects of the Russian Energy Sector on the Security of the Baltic States». Baltic Security & Defence Review. 8: 66–80. ISSN 2382-9230.

- ^ da Graça Carvalho, Maria (April 2012). «EU energy and climate change strategy». Energy. 40 (1): 19–22. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2012.01.012.

- ^ Nader, Philippe Bou (1 June 2017). «The Baltic states should adopt the self-defence pinpricks doctrine: the «accumulation of events» threshold as a deterrent to Russian hybrid warfare». Journal on Baltic Security. 3 (1): 11–24. doi:10.1515/jobs-2017-0003. ISSN 2382-9230.

- ^ «Pilsonības un migrācijas lietu pārvalde – Kļūda 404» (PDF). pmlp.gov.lv. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 September 2020. Retrieved 9 August 2018.

- ^ «POPULATION BY SEX, ETHNIC NATIONALITY AND COUNTY, 1 JANUARY. ADMINISTRATIVE DIVISION AS AT 01.01.2018». pub.stat.ee. Archived from the original on 11 June 2019. Retrieved 26 June 2020.

- ^ «Home – Oficialiosios statistikos portalas». osp.stat.gov.lt.

- ^ «Baltic states – Soviet Republics». Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 5 March 2007.

- ^ Graddol, David. «English Next» (PDF). British Council. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 February 2015.

- ^ «Employees fluent in three languages – it’s the norm in Lithuania». Invest Lithuania. Invest Lithuania. Retrieved 12 May 2021.

- ^ Lukoševičius, Viktoras; Duksa, Tomas. «ERATOSTHENES’ MAP OF THE OECUMENE». Geodesy and Cartography. Taylor & Francis. 38 (2): 84. eISSN 2029-7009. ISSN 2029-6991.

- ^ «Indo-European Etymology: Query result». starling.rinet.ru. Archived from the original on 25 February 2007. Retrieved 28 May 2018.

- ^ Dini, Pierto Umberto (2000) [1997]. Baltu valodas (in Latvian). Translated from Italian by Dace Meiere. Riga: Jānis Roze. ISBN 978-9984-623-96-2.

- ^ a b c Krauklis, Konstantīns (1992). Latviešu etimoloģijas vārdnīca (in Latvian). Vol. I. Rīga: Avots. pp. 103–104. OCLC 28891146.

- ^ a b c Bojtar, Endre (1999). Foreword to the Past: A Cultural History of the Baltic People. Central European University Press. ISBN 9789639116429.

- ^ Skutāns, Gints. «Latvija – jēdziena ģenēze». old.historia.lv. Archived from the original on 22 May 2018. Retrieved 21 May 2018.

- ^ l.l.b, charles mayo (1804). a compendious view of universal history. Archived from the original on 13 May 2018. Retrieved 12 May 2018.

- ^ Mahan, Alfred Thayer (2006). The Life of Nelson. Bexley Publications. ISBN 978-1-4116-7198-0. Archived from the original on 13 May 2018. Retrieved 12 May 2018.

- ^ «Nida and The Curonian Spit, The Insider’s Guide to Visiting». MapTrotting. 23 September 2016. Retrieved 3 January 2019.

- ^ «Population | Statistikaamet».

- ^ https://data.stat.gov.lv/pxweb/lv/OSP_PUB/START__POP__IR__IRS/IRD060/.

- ^ «Main Lithuanian indicators». 21 December 2021.

- ^ a b «Eurostat — Tables, Graphs and Maps Interface (TGM) table».

- ^ «Defense budget to increase by €103 million». news.err.ee/. 23 September 2021.

- ^ «Aizsardzības nozares budžets». mod.gov.lv.

- ^ «2022 METŲ KAM BIUDŽETAS». kam.lt.

- ^ «GINI index (World Bank estimate) | Data». World Bank. Archived from the original on 22 April 2018. Retrieved 28 May 2018.

- ^ «| Human Development Reports». Archived from the original on 14 September 2018. Retrieved 14 September 2018.

Further reading[edit]

- Bojtár, Endre (1999). Forward to the Past – A Cultural History of the Baltic People. Budapest: Central European University Press. ISBN 978-963-9116-42-9.

- Bousfield, Jonathan (2004). Baltic States. Rough Guides. ISBN 978-1-85828-840-6.

- Clerc, Louis; Glover, Nikolas; Jordan, Paul, eds. Histories of Public Diplomacy and Nation Branding in the Nordic and Baltic Countries: Representing the Periphery (Leiden: Brill Nijhoff, 2015). 348 pp. ISBN 978-90-04-30548-9. for an online book review see online review

- D’Amato, Giuseppe (2004). Travel to the Baltic Hansa – The European Union and its enlargement to the East (Book in Italian: Viaggio nell’Hansa baltica – L’Unione europea e l’allargamento ad Est). Milano: Greco&Greco editori. ISBN 978-88-7980-355-7.

- Hiden, John; Patrick Salmon (1991). The Baltic Nations and Europe: Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania in the Twentieth Century. London: Longman. ISBN 978-0-582-08246-5.

- Hiden, John; Vahur Made; David J. Smith (2008). The Baltic Question during the Cold War. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-56934-7.

- Jacobsson, Bengt (2009). The European Union and the Baltic States: Changing forms of governance. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-48276-9.

- Kasekamp, Andres (2010). A History of the Baltic States. London: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-230-01940-9.

- Lane, Thomas; Artis Pabriks; Aldis Purs; David J. Smith (2013). The Baltic States: Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-136-48304-2.

- Malowist, M. “The Economic and Social Development of the Baltic Countries from the Fifteenth to the Seventeenth Centuries.” Economic History Review 12#2 1959, pp. 177–189. online

- Lehti, Marko; David J. Smith, eds. (2003). Post-Cold War Identity Politics – Northern and Baltic Experiences. London/Portland: Frank Cass Publishers. ISBN 978-0-7146-8351-5.

- Lieven, Anatol (1993). The Baltic Revolution: Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, and the Path to Independence. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-05552-8.

- Naylor, Aliide (2020). The Shadow in the East: Vladimir Putin and the New Baltic Front. London: I.B. Tauris. ISBN 978-1788312523.

- O’Connor, Kevin (2006). Culture and Customs of the Baltic States. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-313-33125-1.

- O’Connor, Kevin (2003). The History of the Baltic States. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-313-32355-3.

- Plakans, Andrejs (2011). A Concise History of the Baltic States. Cambridge/New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-54155-8.

- Smith, Graham (1994). The Baltic States: The National Self-determination of Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania. New York: St. Martin’s Press. ISBN 978-0-312-12060-3.

- Palmer, Alan. The Baltic: A new history of the region and its people (New York: Overlook Press, 2006; published in London with the title Northern shores: a history of the Baltic Sea and its peoples (John Murray, 2006))

- Šleivyte, Janina (2010). Russia’s European Agenda and the Baltic States. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-55400-8.

- Vilkauskaite, Dovile O. «From Empire to Independence: The Curious Case of the Baltic States 1917-1922.» (thesis, University of Connecticut, 2013). online; Bibliography pp 70 – 75.

- Williams, Nicola; Debra Herrmann; Cathryn Kemp (2003). Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania (3rd ed.). London: Lonely Planet. ISBN 978-1-74059-132-4.

International peer-reviewed media[edit]

- On the Boundary of Two Worlds: Identity, Freedom, and Moral Imagination in the Baltics (book series)

- Journal of Baltic Studies, journal of the Association for the Advancement of Baltic Studies (AABS)

- Lituanus, a journal dedicated to Lithuanian and Baltic art, history, language, literature and related cultural topics

- The Baltic Course, International Internet Magazine. Analysis and background information on Baltic markets

- Baltic Reports Archived 5 October 2011 at the Wayback Machine, English-language daily news website that covers all three Baltic states

- The Baltic Review, the independent newspaper from the Baltics

- The Baltic Times, an independent weekly newspaper that covers the latest political, economic, business, and cultural events in Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania

- The Baltics Today, news about The Baltics

External links[edit]

- The Baltic Sea Information Centre

- vifanord – a digital library that provides scientific information on the Nordic and Baltic countries

- Baltic states – The article about Baltic states on Encyclopædia Britannica.

- Richter, Klaus: Baltic States and Finland, in: 1914-1918-online. International Encyclopedia of the First World War.

Official statistics of the Baltic states[edit]

- Statistics Estonia

- Statistics Latvia

- Statistics Lithuania