Poetry (derived from the Greek poiesis, «making»), also called verse,[note 1] is a form of literature that uses aesthetic and often rhythmic[1][2][3] qualities of language − such as phonaesthetics, sound symbolism, and metre − to evoke meanings in addition to, or in place of, a prosaic ostensible meaning. A poem is a literary composition, written by a poet, using this principle.

Poetry has a long and varied history, evolving differentially across the globe. It dates back at least to prehistoric times with hunting poetry in Africa and to panegyric and elegiac court poetry of the empires of the Nile, Niger, and Volta River valleys.[4] Some of the earliest written poetry in Africa occurs among the Pyramid Texts written during the 25th century BCE. The earliest surviving Western Asian epic poetry, the Epic of Gilgamesh, was written in Sumerian.

Early poems in the Eurasian continent evolved from folk songs such as the Chinese Shijing, as well as religious hymns (the Sanskrit Rigveda, the Zoroastrian Gathas, the Hurrian songs, and the Hebrew Psalms); or from a need to retell oral epics, as with the Egyptian Story of Sinuhe, the Indian epic poetry, and the Homeric epics, the Iliad and the Odyssey. Ancient Greek attempts to define poetry, such as Aristotle’s Poetics, focused on the uses of speech in rhetoric, drama, song, and comedy. Later attempts concentrated on features such as repetition, verse form, and rhyme, and emphasized the aesthetics which distinguish poetry from more objectively-informative prosaic writing.

Poetry uses forms and conventions to suggest differential interpretations of words, or to evoke emotive responses. Devices such as assonance, alliteration, onomatopoeia, and rhythm may convey musical or incantatory effects. The use of ambiguity, symbolism, irony, and other stylistic elements of poetic diction often leaves a poem open to multiple interpretations. Similarly, figures of speech such as metaphor, simile, and metonymy[5] establish a resonance between otherwise disparate images—a layering of meanings, forming connections previously not perceived. Kindred forms of resonance may exist, between individual verses, in their patterns of rhyme or rhythm.

Some poetry types are unique to particular cultures and genres and respond to characteristics of the language in which the poet writes. Readers accustomed to identifying poetry with Dante, Goethe, Mickiewicz, or Rumi may think of it as written in lines based on rhyme and regular meter. There are, however, traditions, such as Biblical poetry, that use other means to create rhythm and euphony. Much modern poetry reflects a critique of poetic tradition,[6] testing the principle of euphony itself or altogether forgoing rhyme or set rhythm.[7][8]

In an increasingly globalized world, poets often adapt forms, styles, and techniques from diverse cultures and languages. Poets have contributed to the evolution of the linguistic, expressive, and utilitarian qualities of their languages.

A Western cultural tradition (extending at least from Homer to Rilke) associates the production of poetry with inspiration – often by a Muse (either classical or contemporary).

In many poems, the lyrics are spoken by a character, who is called the speaker. This concept differentiates the speaker (character) from the poet (author), which is usually an important distinction: for example, if the poem runs I killed a man in Reno, it is the speaker who is the murderer, not the poet himself.

History[edit]

Early works[edit]

Some scholars believe that the art of poetry may predate literacy, and developed from folk epics and other oral genres.[9][10]

Others, however, suggest that poetry did not necessarily predate writing.[11]

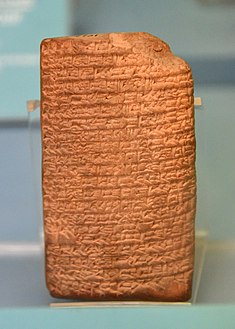

The oldest surviving epic poem, the Epic of Gilgamesh, dates from the 3rd millennium BCE in Sumer (in Mesopotamia, present-day Iraq), and was written in cuneiform script on clay tablets and, later, on papyrus.[12] The Istanbul tablet #2461, dating to c. 2000 BCE, describes an annual rite in which the king symbolically married and mated with the goddess Inanna to ensure fertility and prosperity; some have labelled it the world’s oldest love poem.[13][14] An example of Egyptian epic poetry is The Story of Sinuhe (c. 1800 BCE).[15]

Other ancient epics includes the Greek Iliad and the Odyssey; the Persian Avestan books (the Yasna); the Roman national epic, Virgil’s Aeneid (written between 29 and 19 BCE); and the Indian epics, the Ramayana and the Mahabharata. Epic poetry appears to have been composed in poetic form as an aid to memorization and oral transmission in ancient societies.[11][16]

Other forms of poetry, including such ancient collections of religious hymns as the Indian Sanskrit-language Rigveda, the Avestan Gathas, the Hurrian songs, and the Hebrew Psalms, possibly developed directly from folk songs. The earliest entries in the oldest extant collection of Chinese poetry, the Classic of Poetry (Shijing), were initially lyrics.[17] The Shijing, with its collection of poems and folk songs, was heavily valued by the philosopher Confucius and is considered to be one of the official Confucian classics. His remarks on the subject have become an invaluable source in ancient music theory.[18]

The efforts of ancient thinkers to determine what makes poetry distinctive as a form, and what distinguishes good poetry from bad, resulted in «poetics»—the study of the aesthetics of poetry.[19] Some ancient societies, such as China’s through the Shijing, developed canons of poetic works that had ritual as well as aesthetic importance.[20] More recently, thinkers have struggled to find a definition that could encompass formal differences as great as those between Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales and Matsuo Bashō’s Oku no Hosomichi, as well as differences in content spanning Tanakh religious poetry, love poetry, and rap.[21]

-

The oldest known love poem. Sumerian terracotta tablet #2461 from Nippur, Iraq. Ur III period, 2037–2029 BCE. Ancient Orient Museum, Istanbul

-

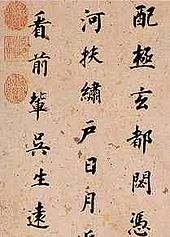

An early Chinese poetics, the Kǒngzǐ Shīlùn (孔子詩論), discussing the Shijing (Classic of Poetry)

Western traditions[edit]

Classical thinkers in the West employed classification as a way to define and assess the quality of poetry. Notably, the existing fragments of Aristotle’s Poetics describe three genres of poetry—the epic, the comic, and the tragic—and develop rules to distinguish the highest-quality poetry in each genre, based on the perceived underlying purposes of the genre.[22] Later aestheticians identified three major genres: epic poetry, lyric poetry, and dramatic poetry, treating comedy and tragedy as subgenres of dramatic poetry.[23]

Aristotle’s work was influential throughout the Middle East during the Islamic Golden Age,[24] as well as in Europe during the Renaissance.[25] Later poets and aestheticians often distinguished poetry from, and defined it in opposition to prose, which they generally understood as writing with a proclivity to logical explication and a linear narrative structure.[26]

This does not imply that poetry is illogical or lacks narration, but rather that poetry is an attempt to render the beautiful or sublime without the burden of engaging the logical or narrative thought-process. English Romantic poet John Keats termed this escape from logic «negative capability».[27] This «romantic» approach views form as a key element of successful poetry because form is abstract and distinct from the underlying notional logic. This approach remained influential into the 20th century.[28]

During the 18th and 19th centuries, there was also substantially more interaction among the various poetic traditions, in part due to the spread of European colonialism and the attendant rise in global trade.[29] In addition to a boom in translation, during the Romantic period numerous ancient works were rediscovered.[30]

20th-century and 21st-century disputes[edit]

Some 20th-century literary theorists rely less on the ostensible opposition of prose and poetry, instead focusing on the poet as simply one who creates using language, and poetry as what the poet creates.[31] The underlying concept of the poet as creator is not uncommon, and some modernist poets essentially do not distinguish between the creation of a poem with words, and creative acts in other media. Yet other modernists challenge the very attempt to define poetry as misguided.[32]

The rejection of traditional forms and structures for poetry that began in the first half of the 20th century coincided with a questioning of the purpose and meaning of traditional definitions of poetry and of distinctions between poetry and prose, particularly given examples of poetic prose and prosaic poetry. Numerous modernist poets have written in non-traditional forms or in what traditionally would have been considered prose, although their writing was generally infused with poetic diction and often with rhythm and tone established by non-metrical means. While there was a substantial formalist reaction within the modernist schools to the breakdown of structure, this reaction focused as much on the development of new formal structures and syntheses as on the revival of older forms and structures.[33]

Postmodernism goes beyond modernism’s emphasis on the creative role of the poet, to emphasize the role of the reader of a text (hermeneutics), and to highlight the complex cultural web within which a poem is read.[34] Today, throughout the world, poetry often incorporates poetic form and diction from other cultures and from the past, further confounding attempts at definition and classification that once made sense within a tradition such as the Western canon.[35]

The early 21st-century poetic tradition appears to continue to strongly orient itself to earlier precursor poetic traditions such as those initiated by Whitman, Emerson, and Wordsworth. The literary critic Geoffrey Hartman (1929–2016) used the phrase «the anxiety of demand» to describe the contemporary response to older poetic traditions as «being fearful that the fact no longer has a form»,[36] building on a trope introduced by Emerson. Emerson had maintained that in the debate concerning poetic structure where either «form» or «fact» could predominate, that one need simply «Ask the fact for the form.» This has been challenged at various levels by other literary scholars such as Harold Bloom (1930–2019), who has stated: «The generation of poets who stand together now, mature and ready to write the major American verse of the twenty-first century, may yet be seen as what Stevens called ‘a great shadow’s last embellishment,’ the shadow being Emerson’s.»[37]

Elements[edit]

Prosody[edit]

Prosody is the study of the meter, rhythm, and intonation of a poem. Rhythm and meter are different, although closely related.[38] Meter is the definitive pattern established for a verse (such as iambic pentameter), while rhythm is the actual sound that results from a line of poetry. Prosody also may be used more specifically to refer to the scanning of poetic lines to show meter.[39]

Rhythm[edit]

The methods for creating poetic rhythm vary across languages and between poetic traditions. Languages are often described as having timing set primarily by accents, syllables, or moras, depending on how rhythm is established, though a language can be influenced by multiple approaches. Japanese is a mora-timed language. Latin, Catalan, French, Leonese, Galician and Spanish are called syllable-timed languages. Stress-timed languages include English, Russian and, generally, German.[40] Varying intonation also affects how rhythm is perceived. Languages can rely on either pitch or tone. Some languages with a pitch accent are Vedic Sanskrit or Ancient Greek. Tonal languages include Chinese, Vietnamese and most Subsaharan languages.[41]

Metrical rhythm generally involves precise arrangements of stresses or syllables into repeated patterns called feet within a line. In Modern English verse the pattern of stresses primarily differentiate feet, so rhythm based on meter in Modern English is most often founded on the pattern of stressed and unstressed syllables (alone or elided).[42] In the classical languages, on the other hand, while the metrical units are similar, vowel length rather than stresses define the meter.[43] Old English poetry used a metrical pattern involving varied numbers of syllables but a fixed number of strong stresses in each line.[44]

The chief device of ancient Hebrew Biblical poetry, including many of the psalms, was parallelism, a rhetorical structure in which successive lines reflected each other in grammatical structure, sound structure, notional content, or all three. Parallelism lent itself to antiphonal or call-and-response performance, which could also be reinforced by intonation. Thus, Biblical poetry relies much less on metrical feet to create rhythm, but instead creates rhythm based on much larger sound units of lines, phrases and sentences.[45] Some classical poetry forms, such as Venpa of the Tamil language, had rigid grammars (to the point that they could be expressed as a context-free grammar) which ensured a rhythm.[46]

Classical Chinese poetics, based on the tone system of Middle Chinese, recognized two kinds of tones: the level (平 píng) tone and the oblique (仄 zè) tones, a category consisting of the rising (上 sháng) tone, the departing (去 qù) tone and the entering (入 rù) tone. Certain forms of poetry placed constraints on which syllables were required to be level and which oblique.

The formal patterns of meter used in Modern English verse to create rhythm no longer dominate contemporary English poetry. In the case of free verse, rhythm is often organized based on looser units of cadence rather than a regular meter. Robinson Jeffers, Marianne Moore, and William Carlos Williams are three notable poets who reject the idea that regular accentual meter is critical to English poetry.[47] Jeffers experimented with sprung rhythm as an alternative to accentual rhythm.[48]

Meter[edit]

In the Western poetic tradition, meters are customarily grouped according to a characteristic metrical foot and the number of feet per line.[50] The number of metrical feet in a line are described using Greek terminology: tetrameter for four feet and hexameter for six feet, for example.[51] Thus, «iambic pentameter» is a meter comprising five feet per line, in which the predominant kind of foot is the «iamb». This metric system originated in ancient Greek poetry, and was used by poets such as Pindar and Sappho, and by the great tragedians of Athens. Similarly, «dactylic hexameter», comprises six feet per line, of which the dominant kind of foot is the «dactyl». Dactylic hexameter was the traditional meter of Greek epic poetry, the earliest extant examples of which are the works of Homer and Hesiod.[52] Iambic pentameter and dactylic hexameter were later used by a number of poets, including William Shakespeare and Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, respectively.[53] The most common metrical feet in English are:[54]

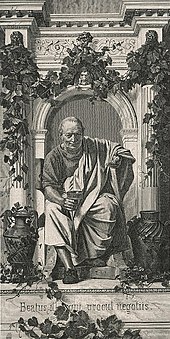

Homer: Roman bust, based on Greek original[55]

- iamb – one unstressed syllable followed by a stressed syllable (e.g. des-cribe, in-clude, re-tract)

- trochee—one stressed syllable followed by an unstressed syllable (e.g. pic-ture, flow-er)

- dactyl – one stressed syllable followed by two unstressed syllables (e.g. an-no-tate, sim-i-lar)

- anapaest—two unstressed syllables followed by one stressed syllable (e.g. com-pre-hend)

- spondee—two stressed syllables together (e.g. heart—beat, four—teen)

- pyrrhic—two unstressed syllables together (rare, usually used to end dactylic hexameter)

There are a wide range of names for other types of feet, right up to a choriamb, a four syllable metric foot with a stressed syllable followed by two unstressed syllables and closing with a stressed syllable. The choriamb is derived from some ancient Greek and Latin poetry.[52] Languages which use vowel length or intonation rather than or in addition to syllabic accents in determining meter, such as Ottoman Turkish or Vedic, often have concepts similar to the iamb and dactyl to describe common combinations of long and short sounds.[56]

Each of these types of feet has a certain «feel,» whether alone or in combination with other feet. The iamb, for example, is the most natural form of rhythm in the English language, and generally produces a subtle but stable verse.[57] Scanning meter can often show the basic or fundamental pattern underlying a verse, but does not show the varying degrees of stress, as well as the differing pitches and lengths of syllables.[58]

There is debate over how useful a multiplicity of different «feet» is in describing meter. For example, Robert Pinsky has argued that while dactyls are important in classical verse, English dactylic verse uses dactyls very irregularly and can be better described based on patterns of iambs and anapests, feet which he considers natural to the language.[59] Actual rhythm is significantly more complex than the basic scanned meter described above, and many scholars have sought to develop systems that would scan such complexity. Vladimir Nabokov noted that overlaid on top of the regular pattern of stressed and unstressed syllables in a line of verse was a separate pattern of accents resulting from the natural pitch of the spoken words, and suggested that the term «scud» be used to distinguish an unaccented stress from an accented stress.[60]

Metrical patterns[edit]

Different traditions and genres of poetry tend to use different meters, ranging from the Shakespearean iambic pentameter and the Homeric dactylic hexameter to the anapestic tetrameter used in many nursery rhymes. However, a number of variations to the established meter are common, both to provide emphasis or attention to a given foot or line and to avoid boring repetition. For example, the stress in a foot may be inverted, a caesura (or pause) may be added (sometimes in place of a foot or stress), or the final foot in a line may be given a feminine ending to soften it or be replaced by a spondee to emphasize it and create a hard stop. Some patterns (such as iambic pentameter) tend to be fairly regular, while other patterns, such as dactylic hexameter, tend to be highly irregular.[61] Regularity can vary between language. In addition, different patterns often develop distinctively in different languages, so that, for example, iambic tetrameter in Russian will generally reflect a regularity in the use of accents to reinforce the meter, which does not occur, or occurs to a much lesser extent, in English.[62]

Some common metrical patterns, with notable examples of poets and poems who use them, include:

- Iambic pentameter (John Milton, Paradise Lost; William Shakespeare, Sonnets)[63]

- Dactylic hexameter (Homer, Iliad; Virgil, Aeneid)[64]

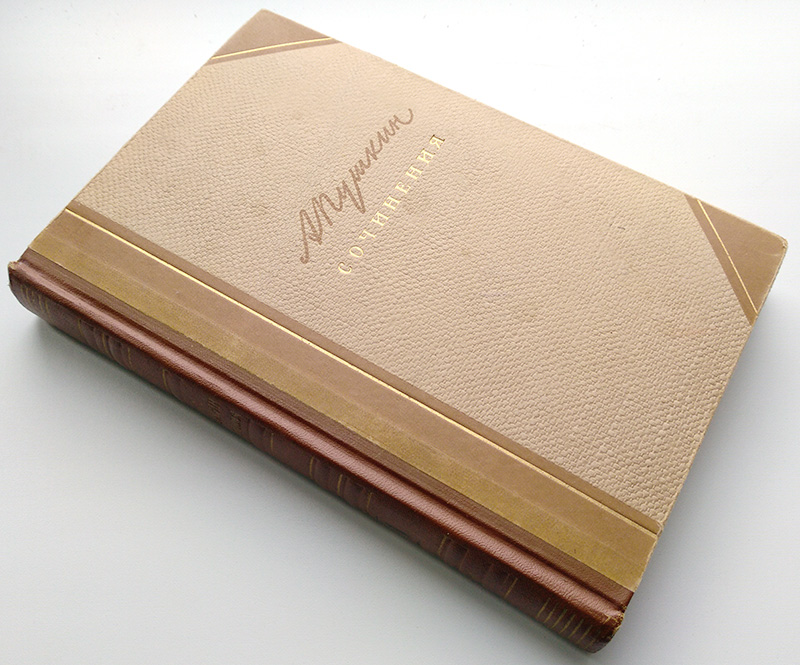

- Iambic tetrameter (Andrew Marvell, «To His Coy Mistress»; Alexander Pushkin, Eugene Onegin; Robert Frost, Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening)[65]

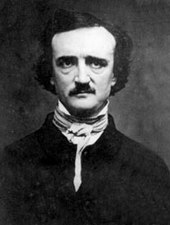

- Trochaic octameter (Edgar Allan Poe, «The Raven»)[66]

- Trochaic tetrameter (Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, The Song of Hiawatha; the Finnish national epic, The Kalevala, is also in trochaic tetrameter, the natural rhythm of Finnish and Estonian)

- Alexandrin (Jean Racine, Phèdre)[67]

Rhyme, alliteration, assonance[edit]

Rhyme, alliteration, assonance and consonance are ways of creating repetitive patterns of sound. They may be used as an independent structural element in a poem, to reinforce rhythmic patterns, or as an ornamental element.[68] They can also carry a meaning separate from the repetitive sound patterns created. For example, Chaucer used heavy alliteration to mock Old English verse and to paint a character as archaic.[69]

Rhyme consists of identical («hard-rhyme») or similar («soft-rhyme») sounds placed at the ends of lines or at locations within lines («internal rhyme»). Languages vary in the richness of their rhyming structures; Italian, for example, has a rich rhyming structure permitting maintenance of a limited set of rhymes throughout a lengthy poem. The richness results from word endings that follow regular forms. English, with its irregular word endings adopted from other languages, is less rich in rhyme.[70] The degree of richness of a language’s rhyming structures plays a substantial role in determining what poetic forms are commonly used in that language.[71]

Alliteration is the repetition of letters or letter-sounds at the beginning of two or more words immediately succeeding each other, or at short intervals; or the recurrence of the same letter in accented parts of words. Alliteration and assonance played a key role in structuring early Germanic, Norse and Old English forms of poetry. The alliterative patterns of early Germanic poetry interweave meter and alliteration as a key part of their structure, so that the metrical pattern determines when the listener expects instances of alliteration to occur. This can be compared to an ornamental use of alliteration in most Modern European poetry, where alliterative patterns are not formal or carried through full stanzas. Alliteration is particularly useful in languages with less rich rhyming structures.

Assonance, where the use of similar vowel sounds within a word rather than similar sounds at the beginning or end of a word, was widely used in skaldic poetry but goes back to the Homeric epic.[72] Because verbs carry much of the pitch in the English language, assonance can loosely evoke the tonal elements of Chinese poetry and so is useful in translating Chinese poetry.[73] Consonance occurs where a consonant sound is repeated throughout a sentence without putting the sound only at the front of a word. Consonance provokes a more subtle effect than alliteration and so is less useful as a structural element.[71]

Rhyming schemes[edit]

In many languages, including modern European languages and Arabic, poets use rhyme in set patterns as a structural element for specific poetic forms, such as ballads, sonnets and rhyming couplets. However, the use of structural rhyme is not universal even within the European tradition. Much modern poetry avoids traditional rhyme schemes. Classical Greek and Latin poetry did not use rhyme.[74] Rhyme entered European poetry in the High Middle Ages, in part under the influence of the Arabic language in Al Andalus (modern Spain).[75] Arabic language poets used rhyme extensively from the first development of literary Arabic in the sixth century, as in their long, rhyming qasidas.[76] Some rhyming schemes have become associated with a specific language, culture or period, while other rhyming schemes have achieved use across languages, cultures or time periods. Some forms of poetry carry a consistent and well-defined rhyming scheme, such as the chant royal or the rubaiyat, while other poetic forms have variable rhyme schemes.[77]

Most rhyme schemes are described using letters that correspond to sets of rhymes, so if the first, second and fourth lines of a quatrain rhyme with each other and the third line do not rhyme, the quatrain is said to have an «aa-ba» rhyme scheme. This rhyme scheme is the one used, for example, in the rubaiyat form.[78] Similarly, an «a-bb-a» quatrain (what is known as «enclosed rhyme») is used in such forms as the Petrarchan sonnet.[79] Some types of more complicated rhyming schemes have developed names of their own, separate from the «a-bc» convention, such as the ottava rima and terza rima.[80] The types and use of differing rhyming schemes are discussed further in the main article.

Form in poetry[edit]

Poetic form is more flexible in modernist and post-modernist poetry and continues to be less structured than in previous literary eras. Many modern poets eschew recognizable structures or forms and write in free verse. Free verse is, however, not «formless» but composed of a series of more subtle, more flexible prosodic elements.[81] Thus poetry remains, in all its styles, distinguished from prose by form;[82] some regard for basic formal structures of poetry will be found in all varieties of free verse, however much such structures may appear to have been ignored.[83] Similarly, in the best poetry written in classic styles there will be departures from strict form for emphasis or effect.[84]

Among major structural elements used in poetry are the line, the stanza or verse paragraph, and larger combinations of stanzas or lines such as cantos. Also sometimes used are broader visual presentations of words and calligraphy. These basic units of poetic form are often combined into larger structures, called poetic forms or poetic modes (see the following section), as in the sonnet.

Lines and stanzas[edit]

Poetry is often separated into lines on a page, in a process known as lineation. These lines may be based on the number of metrical feet or may emphasize a rhyming pattern at the ends of lines. Lines may serve other functions, particularly where the poem is not written in a formal metrical pattern. Lines can separate, compare or contrast thoughts expressed in different units, or can highlight a change in tone.[85] See the article on line breaks for information about the division between lines.

Lines of poems are often organized into stanzas, which are denominated by the number of lines included. Thus a collection of two lines is a couplet (or distich), three lines a triplet (or tercet), four lines a quatrain, and so on. These lines may or may not relate to each other by rhyme or rhythm. For example, a couplet may be two lines with identical meters which rhyme or two lines held together by a common meter alone.[86]

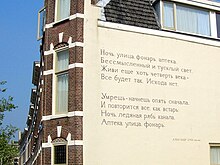

Blok’s Russian poem, «Noch, ulitsa, fonar, apteka» («Night, street, lamp, drugstore»), on a wall in Leiden

Other poems may be organized into verse paragraphs, in which regular rhymes with established rhythms are not used, but the poetic tone is instead established by a collection of rhythms, alliterations, and rhymes established in paragraph form.[87] Many medieval poems were written in verse paragraphs, even where regular rhymes and rhythms were used.[88]

In many forms of poetry, stanzas are interlocking, so that the rhyming scheme or other structural elements of one stanza determine those of succeeding stanzas. Examples of such interlocking stanzas include, for example, the ghazal and the villanelle, where a refrain (or, in the case of the villanelle, refrains) is established in the first stanza which then repeats in subsequent stanzas. Related to the use of interlocking stanzas is their use to separate thematic parts of a poem. For example, the strophe, antistrophe and epode of the ode form are often separated into one or more stanzas.[89]

In some cases, particularly lengthier formal poetry such as some forms of epic poetry, stanzas themselves are constructed according to strict rules and then combined. In skaldic poetry, the dróttkvætt stanza had eight lines, each having three «lifts» produced with alliteration or assonance. In addition to two or three alliterations, the odd-numbered lines had partial rhyme of consonants with dissimilar vowels, not necessarily at the beginning of the word; the even lines contained internal rhyme in set syllables (not necessarily at the end of the word). Each half-line had exactly six syllables, and each line ended in a trochee. The arrangement of dróttkvætts followed far less rigid rules than the construction of the individual dróttkvætts.[90]

Visual presentation[edit]

Even before the advent of printing, the visual appearance of poetry often added meaning or depth. Acrostic poems conveyed meanings in the initial letters of lines or in letters at other specific places in a poem.[91] In Arabic, Hebrew and Chinese poetry, the visual presentation of finely calligraphed poems has played an important part in the overall effect of many poems.[92]

With the advent of printing, poets gained greater control over the mass-produced visual presentations of their work. Visual elements have become an important part of the poet’s toolbox, and many poets have sought to use visual presentation for a wide range of purposes. Some Modernist poets have made the placement of individual lines or groups of lines on the page an integral part of the poem’s composition. At times, this complements the poem’s rhythm through visual caesuras of various lengths, or creates juxtapositions so as to accentuate meaning, ambiguity or irony, or simply to create an aesthetically pleasing form. In its most extreme form, this can lead to concrete poetry or asemic writing.[93][94]

Diction[edit]

Poetic diction treats the manner in which language is used, and refers not only to the sound but also to the underlying meaning and its interaction with sound and form.[95] Many languages and poetic forms have very specific poetic dictions, to the point where distinct grammars and dialects are used specifically for poetry.[96][97] Registers in poetry can range from strict employment of ordinary speech patterns, as favoured in much late-20th-century prosody,[98] through to highly ornate uses of language, as in medieval and Renaissance poetry.[99]

Poetic diction can include rhetorical devices such as simile and metaphor, as well as tones of voice, such as irony. Aristotle wrote in the Poetics that «the greatest thing by far is to be a master of metaphor.»[100] Since the rise of Modernism, some poets have opted for a poetic diction that de-emphasizes rhetorical devices, attempting instead the direct presentation of things and experiences and the exploration of tone.[101] On the other hand, Surrealists have pushed rhetorical devices to their limits, making frequent use of catachresis.[102]

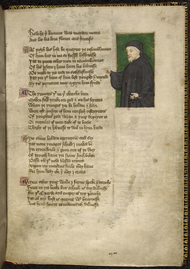

Allegorical stories are central to the poetic diction of many cultures, and were prominent in the West during classical times, the late Middle Ages and the Renaissance. Aesop’s Fables, repeatedly rendered in both verse and prose since first being recorded about 500 BCE, are perhaps the richest single source of allegorical poetry through the ages.[103] Other notables examples include the Roman de la Rose, a 13th-century French poem, William Langland’s Piers Ploughman in the 14th century, and Jean de la Fontaine’s Fables (influenced by Aesop’s) in the 17th century. Rather than being fully allegorical, however, a poem may contain symbols or allusions that deepen the meaning or effect of its words without constructing a full allegory.[104]

Another element of poetic diction can be the use of vivid imagery for effect. The juxtaposition of unexpected or impossible images is, for example, a particularly strong element in surrealist poetry and haiku.[105] Vivid images are often endowed with symbolism or metaphor. Many poetic dictions use repetitive phrases for effect, either a short phrase (such as Homer’s «rosy-fingered dawn» or «the wine-dark sea») or a longer refrain. Such repetition can add a somber tone to a poem, or can be laced with irony as the context of the words changes.[106]

Forms[edit]

Statue of runic singer Petri Shemeikka at Kolmikulmanpuisto Park in Sortavala, Karelia

Specific poetic forms have been developed by many cultures. In more developed, closed or «received» poetic forms, the rhyming scheme, meter and other elements of a poem are based on sets of rules, ranging from the relatively loose rules that govern the construction of an elegy to the highly formalized structure of the ghazal or villanelle.[107] Described below are some common forms of poetry widely used across a number of languages. Additional forms of poetry may be found in the discussions of the poetry of particular cultures or periods and in the glossary.

Sonnet[edit]

Among the most common forms of poetry, popular from the Late Middle Ages on, is the sonnet, which by the 13th century had become standardized as fourteen lines following a set rhyme scheme and logical structure. By the 14th century and the Italian Renaissance, the form had further crystallized under the pen of Petrarch, whose sonnets were translated in the 16th century by Sir Thomas Wyatt, who is credited with introducing the sonnet form into English literature.[108] A traditional Italian or Petrarchan sonnet follows the rhyme scheme ABBA, ABBA, CDECDE, though some variation, perhaps the most common being CDCDCD, especially within the final six lines (or sestet), is common.[109] The English (or Shakespearean) sonnet follows the rhyme scheme ABAB, CDCD, EFEF, GG, introducing a third quatrain (grouping of four lines), a final couplet, and a greater amount of variety in rhyme than is usually found in its Italian predecessors. By convention, sonnets in English typically use iambic pentameter, while in the Romance languages, the hendecasyllable and Alexandrine are the most widely used meters.

Sonnets of all types often make use of a volta, or «turn,» a point in the poem at which an idea is turned on its head, a question is answered (or introduced), or the subject matter is further complicated. This volta can often take the form of a «but» statement contradicting or complicating the content of the earlier lines. In the Petrarchan sonnet, the turn tends to fall around the division between the first two quatrains and the sestet, while English sonnets usually place it at or near the beginning of the closing couplet.

Sonnets are particularly associated with high poetic diction, vivid imagery, and romantic love, largely due to the influence of Petrarch as well as of early English practitioners such as Edmund Spenser (who gave his name to the Spenserian sonnet), Michael Drayton, and Shakespeare, whose sonnets are among the most famous in English poetry, with twenty being included in the Oxford Book of English Verse.[110] However, the twists and turns associated with the volta allow for a logical flexibility applicable to many subjects.[111] Poets from the earliest centuries of the sonnet to the present have used the form to address topics related to politics (John Milton, Percy Bysshe Shelley, Claude McKay), theology (John Donne, Gerard Manley Hopkins), war (Wilfred Owen, e.e. cummings), and gender and sexuality (Carol Ann Duffy). Further, postmodern authors such as Ted Berrigan and John Berryman have challenged the traditional definitions of the sonnet form, rendering entire sequences of «sonnets» that often lack rhyme, a clear logical progression, or even a consistent count of fourteen lines.

Shi[edit]

Shi (simplified Chinese: 诗; traditional Chinese: 詩; pinyin: shī; Wade–Giles: shih) Is the main type of Classical Chinese poetry.[112] Within this form of poetry the most important variations are «folk song» styled verse (yuefu), «old style» verse (gushi), «modern style» verse (jintishi). In all cases, rhyming is obligatory. The Yuefu is a folk ballad or a poem written in the folk ballad style, and the number of lines and the length of the lines could be irregular. For the other variations of shi poetry, generally either a four line (quatrain, or jueju) or else an eight-line poem is normal; either way with the even numbered lines rhyming. The line length is scanned by an according number of characters (according to the convention that one character equals one syllable), and are predominantly either five or seven characters long, with a caesura before the final three syllables. The lines are generally end-stopped, considered as a series of couplets, and exhibit verbal parallelism as a key poetic device.[113] The «old style» verse (Gushi) is less formally strict than the jintishi, or regulated verse, which, despite the name «new style» verse actually had its theoretical basis laid as far back as Shen Yue (441–513 CE), although not considered to have reached its full development until the time of Chen Zi’ang (661–702 CE).[114] A good example of a poet known for his Gushi poems is Li Bai (701–762 CE). Among its other rules, the jintishi rules regulate the tonal variations within a poem, including the use of set patterns of the four tones of Middle Chinese. The basic form of jintishi (sushi) has eight lines in four couplets, with parallelism between the lines in the second and third couplets. The couplets with parallel lines contain contrasting content but an identical grammatical relationship between words. Jintishi often have a rich poetic diction, full of allusion, and can have a wide range of subject, including history and politics.[115][116] One of the masters of the form was Du Fu (712–770 CE), who wrote during the Tang Dynasty (8th century).[117]

Villanelle[edit]

The villanelle is a nineteen-line poem made up of five triplets with a closing quatrain; the poem is characterized by having two refrains, initially used in the first and third lines of the first stanza, and then alternately used at the close of each subsequent stanza until the final quatrain, which is concluded by the two refrains. The remaining lines of the poem have an a-b alternating rhyme.[118] The villanelle has been used regularly in the English language since the late 19th century by such poets as Dylan Thomas,[119] W. H. Auden,[120] and Elizabeth Bishop.[121]

Limerick[edit]

A limerick is a poem that consists of five lines and is often humorous. Rhythm is very important in limericks for the first, second and fifth lines must have seven to ten syllables. However, the third and fourth lines only need five to seven. Lines 1, 2 and 5 rhyme with each other, and lines 3 and 4 rhyme with each other. Practitioners of the limerick included Edward Lear, Lord Alfred Tennyson, Rudyard Kipling, Robert Louis Stevenson.[122]

Tanka[edit]

Tanka is a form of unrhymed Japanese poetry, with five sections totalling 31 on (phonological units identical to morae), structured in a 5-7-5-7-7 pattern.[123] There is generally a shift in tone and subject matter between the upper 5-7-5 phrase and the lower 7-7 phrase. Tanka were written as early as the Asuka period by such poets as Kakinomoto no Hitomaro (fl. late 7th century), at a time when Japan was emerging from a period where much of its poetry followed Chinese form.[124] Tanka was originally the shorter form of Japanese formal poetry (which was generally referred to as «waka»), and was used more heavily to explore personal rather than public themes. By the tenth century, tanka had become the dominant form of Japanese poetry, to the point where the originally general term waka («Japanese poetry») came to be used exclusively for tanka. Tanka are still widely written today.[125]

Haiku[edit]

Haiku is a popular form of unrhymed Japanese poetry, which evolved in the 17th century from the hokku, or opening verse of a renku.[126] Generally written in a single vertical line, the haiku contains three sections totalling 17 on (morae), structured in a 5-7-5 pattern. Traditionally, haiku contain a kireji, or cutting word, usually placed at the end of one of the poem’s three sections, and a kigo, or season-word.[127] The most famous exponent of the haiku was Matsuo Bashō (1644–1694). An example of his writing:[128]

- 富士の風や扇にのせて江戸土産

- fuji no kaze ya oogi ni nosete Edo miyage

- the wind of Mt. Fuji

- I’ve brought on my fan!

- a gift from Edo

Khlong[edit]

The khlong (โคลง, [kʰlōːŋ]) is among the oldest Thai poetic forms. This is reflected in its requirements on the tone markings of certain syllables, which must be marked with mai ek (ไม้เอก, Thai pronunciation: [máj èːk], ◌่) or mai tho (ไม้โท, [máj tʰōː], ◌้). This was likely derived from when the Thai language had three tones (as opposed to today’s five, a split which occurred during the Ayutthaya Kingdom period), two of which corresponded directly to the aforementioned marks. It is usually regarded as an advanced and sophisticated poetic form.[129]

In khlong, a stanza (bot, บท, Thai pronunciation: [bòt]) has a number of lines (bat, บาท, Thai pronunciation: [bàːt], from Pali and Sanskrit pāda), depending on the type. The bat are subdivided into two wak (วรรค, Thai pronunciation: [wák], from Sanskrit varga).[note 2] The first wak has five syllables, the second has a variable number, also depending on the type, and may be optional. The type of khlong is named by the number of bat in a stanza; it may also be divided into two main types: khlong suphap (โคลงสุภาพ, [kʰlōːŋ sù.pʰâːp]) and khlong dan (โคลงดั้น, [kʰlōːŋ dân]). The two differ in the number of syllables in the second wak of the final bat and inter-stanza rhyming rules.[129]

Khlong si suphap[edit]

The khlong si suphap (โคลงสี่สุภาพ, [kʰlōːŋ sìː sù.pʰâːp]) is the most common form still currently employed. It has four bat per stanza (si translates as four). The first wak of each bat has five syllables. The second wak has two or four syllables in the first and third bat, two syllables in the second, and four syllables in the fourth. Mai ek is required for seven syllables and Mai tho is required for four, as shown below. «Dead word» syllables are allowed in place of syllables which require mai ek, and changing the spelling of words to satisfy the criteria is usually acceptable.

Ode[edit]

Main article: Ode

Odes were first developed by poets writing in ancient Greek, such as Pindar, and Latin, such as Horace. Forms of odes appear in many of the cultures that were influenced by the Greeks and Latins.[130] The ode generally has three parts: a strophe, an antistrophe, and an epode. The strophe and the antistrophe of the ode possess similar metrical structures and, depending on the tradition, similar rhyme structures. In contrast, the epode is written with a different scheme and structure. Odes have a formal poetic diction and generally deal with a serious subject. The strophe and antistrophe look at the subject from different, often conflicting, perspectives, with the epode moving to a higher level to either view or resolve the underlying issues. Odes are often intended to be recited or sung by two choruses (or individuals), with the first reciting the strophe, the second the antistrophe, and both together the epode.[131] Over time, differing forms for odes have developed with considerable variations in form and structure, but generally showing the original influence of the Pindaric or Horatian ode. One non-Western form which resembles the ode is the qasida in Arabic poetry.[132]

Ghazal[edit]

The ghazal (also ghazel, gazel, gazal, or gozol) is a form of poetry common in Arabic, Bengali, Persian and Urdu. In classic form, the ghazal has from five to fifteen rhyming couplets that share a refrain at the end of the second line. This refrain may be of one or several syllables and is preceded by a rhyme. Each line has an identical meter. The ghazal often reflects on a theme of unattainable love or divinity.[133]

As with other forms with a long history in many languages, many variations have been developed, including forms with a quasi-musical poetic diction in Urdu.[134] Ghazals have a classical affinity with Sufism, and a number of major Sufi religious works are written in ghazal form. The relatively steady meter and the use of the refrain produce an incantatory effect, which complements Sufi mystical themes well.[135] Among the masters of the form is Rumi, a 13th-century Persian poet.[136]

One of the most famous poet in this type of poetry is Hafez, whose poems often include the theme of exposing hypocrisy. His life and poems have been the subject of much analysis, commentary and interpretation, influencing post-fourteenth century Persian writing more than any other author.[137][138] The West-östlicher Diwan of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, a collection of lyrical poems, is inspired by the Persian poet Hafez.[139][140][141]

Genres[edit]

In addition to specific forms of poems, poetry is often thought of in terms of different genres and subgenres. A poetic genre is generally a tradition or classification of poetry based on the subject matter, style, or other broader literary characteristics.[142] Some commentators view genres as natural forms of literature. Others view the study of genres as the study of how different works relate and refer to other works.[143]

Narrative poetry[edit]

Narrative poetry is a genre of poetry that tells a story. Broadly it subsumes epic poetry, but the term «narrative poetry» is often reserved for smaller works, generally with more appeal to human interest. Narrative poetry may be the oldest type of poetry. Many scholars of Homer have concluded that his Iliad and Odyssey were composed of compilations of shorter narrative poems that related individual episodes. Much narrative poetry—such as Scottish and English ballads, and Baltic and Slavic heroic poems—is performance poetry with roots in a preliterate oral tradition. It has been speculated that some features that distinguish poetry from prose, such as meter, alliteration and kennings, once served as memory aids for bards who recited traditional tales.[144]

Notable narrative poets have included Ovid, Dante, Juan Ruiz, William Langland, Chaucer, Fernando de Rojas, Luís de Camões, Shakespeare, Alexander Pope, Robert Burns, Adam Mickiewicz, Alexander Pushkin, Edgar Allan Poe, Alfred Tennyson, and Anne Carson.

Lyric poetry[edit]

Lyric poetry is a genre that, unlike epic and dramatic poetry, does not attempt to tell a story but instead is of a more personal nature. Poems in this genre tend to be shorter, melodic, and contemplative. Rather than depicting characters and actions, it portrays the poet’s own feelings, states of mind, and perceptions.[145] Notable poets in this genre include Christine de Pizan, John Donne, Charles Baudelaire, Gerard Manley Hopkins, Antonio Machado, and Edna St. Vincent Millay.

Epic poetry[edit]

Epic poetry is a genre of poetry, and a major form of narrative literature. This genre is often defined as lengthy poems concerning events of a heroic or important nature to the culture of the time. It recounts, in a continuous narrative, the life and works of a heroic or mythological person or group of persons.[146] Examples of epic poems are Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey, Virgil’s Aeneid, the Nibelungenlied, Luís de Camões’ Os Lusíadas, the Cantar de Mio Cid, the Epic of Gilgamesh, the Mahabharata, Lönnrot’s Kalevala, Valmiki’s Ramayana, Ferdowsi’s Shahnama, Nizami (or Nezami)’s Khamse (Five Books), and the Epic of King Gesar. While the composition of epic poetry, and of long poems generally, became less common in the west after the early 20th century, some notable epics have continued to be written. The Cantos by Ezra Pound, Helen in Egypt by H.D., and Paterson by William Carlos Williams are examples of modern epics. Derek Walcott won a Nobel prize in 1992 to a great extent on the basis of his epic, Omeros.[147]

Satirical poetry[edit]

Poetry can be a powerful vehicle for satire. The Romans had a strong tradition of satirical poetry, often written for political purposes. A notable example is the Roman poet Juvenal’s satires.[148]

The same is true of the English satirical tradition. John Dryden (a Tory), the first Poet Laureate, produced in 1682 Mac Flecknoe, subtitled «A Satire on the True Blue Protestant Poet, T.S.» (a reference to Thomas Shadwell).[149] Satirical poets outside England include Poland’s Ignacy Krasicki, Azerbaijan’s Sabir, Portugal’s Manuel Maria Barbosa du Bocage, and Korea’s Kim Kirim, especially noted for his Gisangdo.

Elegy[edit]

An elegy is a mournful, melancholy or plaintive poem, especially a lament for the dead or a funeral song. The term «elegy,» which originally denoted a type of poetic meter (elegiac meter), commonly describes a poem of mourning. An elegy may also reflect something that seems to the author to be strange or mysterious. The elegy, as a reflection on a death, on a sorrow more generally, or on something mysterious, may be classified as a form of lyric poetry.[150][151]

Notable practitioners of elegiac poetry have included Propertius, Jorge Manrique, Jan Kochanowski, Chidiock Tichborne, Edmund Spenser, Ben Jonson, John Milton, Thomas Gray, Charlotte Smith, William Cullen Bryant, Percy Bysshe Shelley, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Evgeny Baratynsky, Alfred Tennyson, Walt Whitman, Antonio Machado, Juan Ramón Jiménez, William Butler Yeats, Rainer Maria Rilke, and Virginia Woolf.

Verse fable[edit]

The fable is an ancient literary genre, often (though not invariably) set in verse. It is a succinct story that features anthropomorphised animals, legendary creatures, plants, inanimate objects, or forces of nature that illustrate a moral lesson (a «moral»). Verse fables have used a variety of meter and rhyme patterns.[152]

Notable verse fabulists have included Aesop, Vishnu Sarma, Phaedrus, Marie de France, Robert Henryson, Biernat of Lublin, Jean de La Fontaine, Ignacy Krasicki, Félix María de Samaniego, Tomás de Iriarte, Ivan Krylov and Ambrose Bierce.

Dramatic poetry[edit]

Dramatic poetry is drama written in verse to be spoken or sung, and appears in varying, sometimes related forms in many cultures. Greek tragedy in verse dates to the 6th century B.C., and may have been an influence on the development of Sanskrit drama,[153] just as Indian drama in turn appears to have influenced the development of the bianwen verse dramas in China, forerunners of Chinese Opera.[154] East Asian verse dramas also include Japanese Noh. Examples of dramatic poetry in Persian literature include Nizami’s two famous dramatic works, Layla and Majnun and Khosrow and Shirin, Ferdowsi’s tragedies such as Rostam and Sohrab, Rumi’s Masnavi, Gorgani’s tragedy of Vis and Ramin, and Vahshi’s tragedy of Farhad. American poets of 20th century revive dramatic poetry, including Ezra Pound in “Sestina: Altaforte,”[155] T.S. Eliot with “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock,”.[156][157]

Speculative poetry[edit]

Speculative poetry, also known as fantastic poetry (of which weird or macabre poetry is a major sub-classification), is a poetic genre which deals thematically with subjects which are «beyond reality», whether via extrapolation as in science fiction or via weird and horrific themes as in horror fiction. Such poetry appears regularly in modern science fiction and horror fiction magazines. Edgar Allan Poe is sometimes seen as the «father of speculative poetry».[158] Poe’s most remarkable achievement in the genre was his anticipation, by three-quarters of a century, of the Big Bang theory of the universe’s origin, in his then much-derided 1848 essay (which, due to its very speculative nature, he termed a «prose poem»), Eureka: A Prose Poem.[159][160]

Prose poetry[edit]

Prose poetry is a hybrid genre that shows attributes of both prose and poetry. It may be indistinguishable from the micro-story (a.k.a. the «short short story», «flash fiction»). While some examples of earlier prose strike modern readers as poetic, prose poetry is commonly regarded as having originated in 19th-century France, where its practitioners included Aloysius Bertrand, Charles Baudelaire, Stéphane Mallarmé, and Arthur Rimbaud.[161] Since the late 1980s especially, prose poetry has gained increasing popularity, with entire journals, such as The Prose Poem: An International Journal,[162] Contemporary Haibun Online,[163] and Haibun Today[164] devoted to that genre and its hybrids. Latin American poets of the 20th century who wrote prose poems include Octavio Paz and Alejandra Pizarnik.

Light poetry[edit]

Light poetry, or light verse, is poetry that attempts to be humorous. Poems considered «light» are usually brief, and can be on a frivolous or serious subject, and often feature word play, including puns, adventurous rhyme and heavy alliteration. Although a few free verse poets have excelled at light verse outside the formal verse tradition, light verse in English usually obeys at least some formal conventions. Common forms include the limerick, the clerihew, and the double dactyl.

While light poetry is sometimes condemned as doggerel, or thought of as poetry composed casually, humor often makes a serious point in a subtle or subversive way. Many of the most renowned «serious» poets have also excelled at light verse. Notable writers of light poetry include Lewis Carroll, Ogden Nash, X. J. Kennedy, Willard R. Espy, Shel Silverstein, and Wendy Cope.

Slam poetry[edit]

Slam poetry as a genre originated in 1986 in Chicago, Illinois, when Marc Kelly Smith organized the first slam.[165][166] Slam performers comment emotively, aloud before an audience, on personal, social, or other matters. Slam focuses on the aesthetics of word play, intonation, and voice inflection. Slam poetry is often competitive, at dedicated «poetry slam» contests.[167]

Performance poetry[edit]

Performance poetry, similar to slam in that it occurs before an audience, is a genre of poetry that may fuse a variety of disciplines in a performance of a text, such as dance, music, and other aspects of performance art.[168][169]

Language happenings[edit]

The term happening was popularized by the avante garde movements in the 1950s and regard spontaneous, site-specific performances.[170] Language happenings, termed from the poetics collective OBJECT:PARADISE in 2018, are events which focus less on poetry as a prescriptive literary genre, but more as a descriptive linguistic act and performance, often incorporating broader forms of performance art while poetry is read or created in that moment.[171][172]

See also[edit]

- Anti-poetry

- Digital poetry

- Glossary of poetry terms

- Improvisation

- List of poetry groups and movements

- Oral poetry

- Outline of poetry

- Persona poetry

- Phonestheme

- Phono-semantic matching

- Poetry reading

- Rhapsode

- Semantic differential

- Spoken word

Notes[edit]

- ^ A synecdoche, assuming the poetic element of verse as representative of the entire art form. It is often used when comparing poetry to prose.

- ^ In literary studies, line in western poetry is translated as bat. However, in some forms, the unit is more equivalent to wak. To avoid confusion, this article will refer to wak and bat instead of line, which may refer to either.

References[edit]

Citations[edit]

- ^ «Poetry». Oxford Dictionaries. Oxford University Press. 2013. Archived from the original on 18 June 2013.

poetry […] Literary work in which the expression of feelings and ideas is given intensity by the use of distinctive style and rhythm; poems collectively or as a genre of literature.

- ^ «Poetry». Merriam-Webster. Merriam-Webster, Inc. 2013.

poetry […] 2 : writing that formulates a concentrated imaginative awareness of experience in language chosen and arranged to create a specific emotional response through meaning, sound, and rhythm

- ^ «Poetry». Dictionary.com. Dictionary.com, LLC. 2013.

poetry […] 1 the art of rhythmical composition, written or spoken, for exciting pleasure by beautiful, imaginative, or elevated thoughts.

- ^ Ruth Finnegan, Oral Literature in Africa, Open Book Publishers, 2012.

- ^ Strachan, John R.; Terry, Richard G. (2000). Poetry: an introduction. Edinburgh University Press. p. 119. ISBN 978-0-8147-9797-6.

- ^ Eliot, T. S. (1999) [1923]. «The Function of Criticism». Selected Essays. Faber & Faber. pp. 13–34. ISBN 978-0-15-180387-3.

- ^ Longenbach, James (1997). Modern Poetry After Modernism. Oxford University Press. p. 9, 103. ISBN 978-0-19-510178-2.

- ^ Schmidt, Michael, ed. (1999). The Harvill Book of Twentieth-Century Poetry in English. Harvill Press. pp. xxvii–xxxiii. ISBN 978-1-86046-735-6.

- ^ Höivik, Susan; Luger, Kurt (3 June 2009). «Folk Media for Biodiversity Conservation: A Pilot Project from the Himalaya-Hindu Kush». International Communication Gazette. 71 (4): 321–346. doi:10.1177/1748048509102184. S2CID 143947520.

- ^ Goody, Jack (1987). The Interface Between the Written and the Oral. Cambridge University Press. p. 78. ISBN 978-0-521-33794-6.

[…] poetry, tales, recitations of various kinds existed long before writing was introduced and these oral forms continued in modified ‘oral’ forms, even after the establishment of a written literature.

- ^ a b Goody, Jack (1987). The Interface Between the Written and the Oral. Cambridge University Press. p. 98. ISBN 978-0-521-33794-6.

- ^ The Epic of Gilgamesh. Translated by Sanders, N. K. (Revised ed.). Penguin Books. 1972. pp. 7–8.

- ^ Mark, Joshua J. (13 August 2014). «The World’s Oldest Love Poem».

‘[…] What I held in my hand was one of the oldest love songs written down by the hand of man […].’

- ^ Arsu, Şebnem (14 February 2006). «Oldest Line in the World». The New York Times. Retrieved 1 May 2015.

A small tablet in a special display this month in the Istanbul Museum of the Ancient Orient is thought to be the oldest love poem ever found, the words of a lover from more than 4,000 years ago.

- ^ Chyla, Julia; Rosińska-Balik, Karolina; Debowska-Ludwin, Joanna (30 June 2017). Current Research in Egyptology 17. Oxbow Books. pp. 159–161. ISBN 978-1-78570-603-5.

- ^ Ahl, Frederick; Roisman, Hanna M. (1996). The Odyssey Re-Formed. Cornell University Press. pp. 1–26. ISBN 978-0-8014-8335-6..

- ^ Ebrey, Patricia (1993). Chinese Civilisation: A Sourcebook (2nd ed.). The Free Press. pp. 11–13. ISBN 978-0-02-908752-7.

- ^ Cai, Zong-qi (July 1999). «In Quest of Harmony: Plato and Confucius on Poetry». Philosophy East and West. 49 (3): 317–345. doi:10.2307/1399898. JSTOR 1399898.

- ^ Abondolo, Daniel (2001). A poetics handbook: verbal art in the European tradition. Curzon. pp. 52–53. ISBN 978-0-7007-1223-6.

- ^ Gentz, Joachim (2008). «Ritual Meaning of Textual Form: Evidence from Early Commentaries of the Historiographic and Ritual Traditions». In Kern, Martin (ed.). Text and Ritual in Early China. University of Washington Press. pp. 124–48. ISBN 978-0-295-98787-3.

- ^ Habib, Rafey (2005). A history of literary criticism. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 607–09, 620. ISBN 978-0-631-23200-1.

- ^ Heath, Malcolm, ed. (1997). Aristotle’s Poetics. Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-044636-4.

- ^ Frow, John (2007). Genre (Reprint ed.). Routledge. pp. 57–59. ISBN 978-0-415-28063-1.

- ^ Boggess, William F. (1968). «‘Hermannus Alemannus’ Latin Anthology of Arabic Poetry». Journal of the American Oriental Society. 88 (4): 657–70. doi:10.2307/598112. JSTOR 598112. Burnett, Charles (2001). «Learned Knowledge of Arabic Poetry, Rhymed Prose, and Didactic Verse from Petrus Alfonsi to Petrarch». Poetry and Philosophy in the Middle Ages: A Festschrift for Peter Dronke. Brill Academic Publishers. pp. 29–62. ISBN 978-90-04-11964-2.

- ^ Grendler, Paul F. (2004). The Universities of the Italian Renaissance. Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 239. ISBN 978-0-8018-8055-1.

- ^ Kant, Immanuel (1914). Critique of Judgment. Translated by Bernard, J. H. Macmillan. p. 131. Kant argues that the nature of poetry as a self-consciously abstract and beautiful form raises it to the highest level among the verbal arts, with tone or music following it, and only after that the more logical and narrative prose.

- ^ Ou, Li (2009). Keats and negative capability. Continuum. pp. 1–3. ISBN 978-1-4411-4724-0.

- ^ Watten, Barrett (2003). The constructivist moment: from material text to cultural poetics. Wesleyan University Press. pp. 17–19. ISBN 978-0-8195-6610-2.

- ^ Abu-Mahfouz, Ahmad (2008). «Translation as a Blending of Cultures». Journal of Translation. 4 (1): 1–5. doi:10.54395/jot-x8fne.

- ^ Highet, Gilbert (1985). The classical tradition: Greek and Roman influences on western literature (Reissued ed.). Oxford University Press. pp. 355, 360, 479. ISBN 978-0-19-500206-5.

- ^ Wimsatt, William K. Jr.; Brooks, Cleanth (1957). Literary Criticism: A Short History. Vintage Books. p. 374.

- ^ Johnson, Jeannine (2007). Why write poetry?: modern poets defending their art. Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. p. 148. ISBN 978-0-8386-4105-7.

- ^ Jenkins, Lee M.; Davis, Alex, eds. (2007). The Cambridge companion to modernist poetry. Cambridge University Press. pp. 1–7, 38, 156. ISBN 978-0-521-61815-1.

- ^ Barthes, Roland (1978). «Death of the Author». Image-Music-Text. Farrar, Straus & Giroux. pp. 142–48.

- ^ Connor, Steven (1997). Postmodernist culture: an introduction to theories of the contemporary (2nd ed.). Blackwell. pp. 123–28. ISBN 978-0-631-20052-9.

- ^ Preminger, Alex (1975). Princeton Encyclopaedia of Poetry and Poetics (enlarged ed.). London and Basingstoke: Macmillan Press. p. 919. ISBN 9781349156177.

- ^

Bloom, Harold (2010) [1986]. «Introduction». In Bloom, Harold (ed.). Contemporary Poets. Bloom’s modern critical views (revised ed.). New York: Infobase Publishing. p. 7. ISBN 9781604135886. Retrieved 7 May 2019.The generation of poets who stand together now, mature and ready to write the major American verse of the twenty-first century, may yet be seen as what Stevens called ‘a great shadow’s last embellishment,’ the shadow being Emerson’s.

- ^ Pinsky 1998, p. 52

- ^ Fussell 1965, pp. 20–21

- ^ Schülter, Julia (2005). Rhythmic Grammar. Walter de Gruyter. pp. 24, 304, 332.

- ^ Yip, Moira (2002). Tone. Cambridge textbooks in linguistics. Cambridge University Press. pp. 1–4, 130. ISBN 978-0-521-77314-0.

- ^ Fussell 1965, p. 12

- ^ Jorgens, Elise Bickford (1982). The well-tun’d word : musical interpretations of English poetry, 1597–1651. University of Minnesota Press. p. 23. ISBN 978-0-8166-1029-7.

- ^ Fussell 1965, pp. 75–76

- ^ Walker-Jones, Arthur (2003). Hebrew for biblical interpretation. Society of Biblical Literature. pp. 211–13. ISBN 978-1-58983-086-8.

- ^ Bala Sundara Raman, L.; Ishwar, S.; Kumar Ravindranath, Sanjeeth (2003). «Context Free Grammar for Natural Language Constructs: An implementation for Venpa Class of Tamil Poetry». Tamil Internet: 128–36. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.3.7738.

- ^ Hartman, Charles O. (1980). Free Verse An Essay on Prosody. Northwestern University Press. pp. 24, 44, 47. ISBN 978-0-8101-1316-9.

- ^ Hollander 1981, p. 22

- ^ McClure, Laura K. (2002), Sexuality and Gender in the Classical World: Readings and Sources, Oxford, England: Blackwell Publishers, p. 38, ISBN 978-0-631-22589-8

- ^ Corn 1997, p. 24

- ^ Corn 1997, pp. 25, 34

- ^ a b Annis, William S. (January 2006). «Introduction to Greek Meter» (PDF). Aoidoi. pp. 1–15.

- ^ «Examples of English metrical systems» (PDF). Fondazione Universitaria in provincia di Belluno. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 March 2012. Retrieved 10 December 2011.

- ^ Fussell 1965, pp. 23–24

- ^ «Portrait Bust». britishmuseum.org. The British Museum.

- ^ Kiparsky, Paul (September 1975). «Stress, Syntax, and Meter». Language. 51 (3): 576–616. doi:10.2307/412889. JSTOR 412889.

- ^ Thompson, John (1961). The Founding of English Meter. Columbia University Press. p. 36.

- ^ Pinsky 1998, pp. 11–24

- ^ Pinsky 1998, p. 66

- ^ Nabokov, Vladimir (1964). Notes on Prosody. Bollingen Foundation. pp. 9–13. ISBN 978-0-691-01760-0.

- ^ Fussell 1965, pp. 36–71

- ^ Nabokov, Vladimir (1964). Notes on Prosody. Bollingen Foundation. pp. 46–47. ISBN 978-0-691-01760-0.

- ^ Adams 1997, p. 206

- ^ Adams 1997, p. 63

- ^ «What is Tetrameter?». tetrameter.com. Retrieved 10 December 2011.

- ^ Adams 1997, p. 60

- ^ James, E. D.; Jondorf, G. (1994). Racine: Phèdre. Cambridge University Press. pp. 32–34. ISBN 978-0-521-39721-6.

- ^ Corn 1997, p. 65

- ^ Osberg, Richard H. (2001). «‘I kan nat geeste’: Chaucer’s Artful Alliteration». In Gaylord, Alan T. (ed.). Essays on the art of Chaucer’s Verse. Routledge. pp. 195–228. ISBN 978-0-8153-2951-0.

- ^ Alighieri, Dante (1994). «Introduction». The Inferno of Dante: A New Verse Translation. Translated by Pinsky, Robert. Farrar, Straus & Giroux. ISBN 978-0-374-17674-7.

- ^ a b Kiparsky, Paul (Summer 1973). «The Role of Linguistics in a Theory of Poetry». Daedalus. 102 (3): 231–44.

- ^ Russom, Geoffrey (1998). Beowulf and old Germanic metre. Cambridge University Press. pp. 64–86. ISBN 978-0-521-59340-3.

- ^ Liu, James J. Y. (1990). Art of Chinese Poetry. University of Chicago Press. pp. 21–22. ISBN 978-0-226-48687-1.

- ^ Wesling, Donald (1980). The chances of rhyme. University of California Press. pp. x–xi, 38–42. ISBN 978-0-520-03861-5.

- ^ Menocal, María Rosa (2003). The Arabic Role in Medieval Literary History. University of Pennsylvania. p. 88. ISBN 978-0-8122-1324-9.

- ^ Sperl, Stefan, ed. (1996). Qasida poetry in Islamic Asia and Africa. Brill. p. 49. ISBN 978-90-04-10387-0.

- ^ Adams 1997, pp. 71–104

- ^ Fussell 1965, p. 27

- ^ Adams 1997, pp. 88–91

- ^ Corn 1997, pp. 81–82, 85

- ^ «FREE VERSE». 25 May 2015. Retrieved 22 May 2021.

- ^ «Forms of verse: Free verse [Victoria and Albert Museum]». 4 July 2011. Retrieved 22 May 2021.

- ^ Whitworth, Michael H. (2010). Reading modernist poetry. Wiley-Blackwell. p. 74. ISBN 978-1-4051-6731-4.

- ^ Hollander 1981, pp. 50–51

- ^ Corn 1997, pp. 7–13

- ^ Corn 1997, pp. 78–82

- ^ Corn 1997, p. 78

- ^ Dalrymple, Roger, ed. (2004). Middle English Literature: a guide to criticism. Blackwell Publishing. p. 10. ISBN 978-0-631-23290-2.

- ^ Corn 1997, pp. 78–79

- ^ McTurk, Rory, ed. (2004). Companion to Old Norse-Icelandic Literature and Culture. Blackwell. pp. 269–80. ISBN 978-1-4051-3738-6.

- ^ Freedman, David Noel (July 1972). «Acrostics and Metrics in Hebrew Poetry». Harvard Theological Review. 65 (3): 367–92. doi:10.1017/s0017816000001620. S2CID 162853305.

- ^ Kampf, Robert (2010). Reading the Visual – 17th century poetry and visual culture. GRIN Verlag. pp. 4–6. ISBN 978-3-640-60011-3.

- ^ Bohn, Willard (1993). The aesthetics of visual poetry. University of Chicago Press. pp. 1–8. ISBN 978-0-226-06325-6.

- ^ Sterling, Bruce (13 July 2009). «Web Semantics: Asemic writing». Wired. Archived from the original on 27 October 2009. Retrieved 10 December 2011.

- ^ Barfield, Owen (1987). Poetic diction: a study in meaning (2nd ed.). Wesleyan University Press. p. 41. ISBN 978-0-8195-6026-1.

- ^ Sheets, George A. (Spring 1981). «The Dialect Gloss, Hellenistic Poetics and Livius Andronicus». American Journal of Philology. 102 (1): 58–78. doi:10.2307/294154. JSTOR 294154.

- ^ Blank, Paula (1996). Broken English: dialects and the politics of language in Renaissance writings. Routledge. pp. 29–31. ISBN 978-0-415-13779-9.

- ^ Perloff, Marjorie (2002). 21st-century modernism: the new poetics. Blackwell Publishers. p. 2. ISBN 978-0-631-21970-5.

- ^ Paden, William D., ed. (2000). Medieval lyric: genres in historical context. University of Illinois Press. p. 193. ISBN 978-0-252-02536-5.

- ^ The Poetics of Aristotle. Gutenberg. 1974. p. 22.

- ^ Davis, Alex; Jenkins, Lee M., eds. (2007). The Cambridge companion to modernist poetry. Cambridge University Press. pp. 90–96. ISBN 978-0-521-61815-1.

- ^ San Juan, E. Jr. (2004). Working through the contradictions from cultural theory to critical practice. Bucknell University Press. pp. 124–25. ISBN 978-0-8387-5570-9.

- ^ Treip, Mindele Anne (1994). Allegorical poetics and the epic: the Renaissance tradition to Paradise Lost. University Press of Kentucky. p. 14. ISBN 978-0-8131-1831-4.

- ^ Crisp, P. (1 November 2005). «Allegory and symbol – a fundamental opposition?». Language and Literature. 14 (4): 323–38. doi:10.1177/0963947005051287. S2CID 170517936.

- ^ Gilbert, Richard (2004). «The Disjunctive Dragonfly». Modern Haiku. 35 (2): 21–44.

- ^ Hollander 1981, pp. 37–46

- ^ Fussell 1965, pp. 160–65

- ^ Corn 1997, p. 94

- ^ Minta, Stephen (1980). Petrarch and Petrarchism. Manchester University Press. pp. 15–17. ISBN 978-0-7190-0748-4.

- ^ Quiller-Couch, Arthur, ed. (1900). Oxford Book of English Verse. Oxford University Press.

- ^ Fussell 1965, pp. 119–33

- ^ Watson, Burton (1971). CHINESE LYRICISM: Shih Poetry from the Second to the Twelfth Century. (New York: Columbia University Press). ISBN 0-231-03464-4, 1

- ^ Watson, Burton (1971). Chinese Lyricism: Shih Poetry from the Second to the Twelfth Century. (New York: Columbia University Press). ISBN 0-231-03464-4, 1–2 and 15–18

- ^ Watson, Burton (1971). Chinese Lyricism: Shih Poetry from the Second to the Twelfth Century. (New York: Columbia University Press). ISBN 0-231-03464-4, 111 and 115

- ^ Faurot, Jeannette L (1998). Drinking with the moon. China Books & Periodicals. p. 30. ISBN 978-0-8351-2639-7.

- ^ Wang, Yugen (1 June 2004). «Shige: The Popular Poetics of Regulated Verse». T’ang Studies. 2004 (22): 81–125. doi:10.1179/073750304788913221. S2CID 163239068.

- ^ Schirokauer, Conrad (1989). A brief history of Chinese and Japanese civilizations (2nd ed.). Harcourt Brace Jovanovich. p. 119. ISBN 978-0-15-505569-8.

- ^ Kumin, Maxine (2002). «Gymnastics: The Villanelle». In Varnes, Kathrine (ed.). An Exaltation of Forms: Contemporary Poets Celebrate the Diversity of Their Art. University of Michigan Press. p. 314. ISBN 978-0-472-06725-1.

- ^ «Do Not Go Gentle into that Good Night» in Thomas, Dylan (1952). In Country Sleep and Other Poems. New Directions Publications. p. 18.

- ^ «Villanelle», in Auden, W. H. (1945). Collected Poems. Random House.

- ^ «One Art», in Bishop, Elizabeth (1976). Geography III. Farrar, Straus & Giroux.

- ^ Poets, Academy of American. «Limerick | Academy of American Poets». poets.org. Retrieved 10 October 2020.

Limericks can be found in the work of Lord Alfred Tennyson, Rudyard Kipling, Robert Louis Stevenson

- ^ Samy Alim, H.; Ibrahim, Awad; Pennycook, Alastair, eds. (2009). Global linguistic flows. Taylor & Francis. p. 181. ISBN 978-0-8058-6283-6.

- ^ Brower, Robert H.; Miner, Earl (1988). Japanese court poetry. Stanford University Press. pp. 86–92. ISBN 978-0-8047-1524-9.

- ^ McCllintock, Michael; Ness, Pamela Miller; Kacian, Jim, eds. (2003). The tanka anthology: tanka in English from around the world. Red Moon Press. pp. xxx–xlviii. ISBN 978-1-893959-40-8.

- ^ Corn 1997, p. 117

- ^ Ross, Bruce, ed. (1993). Haiku moment: an anthology of contemporary North American haiku. Charles E. Tuttle Co. p. xiii. ISBN 978-0-8048-1820-9.

- ^ Yanagibori, Etsuko. «Basho’s Haiku on the theme of Mt. Fuji». The personal notebook of Etsuko Yanagibori. Archived from the original on 28 May 2007.

- ^ a b «โคลง Khloong». Thai Language Audio Resource Center. Thammasat University. Retrieved 6 March 2012. Reproduced form Hudak, Thomas John (1990). The indigenization of Pali meters in Thai poetry. Monographs in International Studies, Southeast Asia Series. Athens, Ohio: Ohio University Center for International Studies. ISBN 978-0-89680-159-2.

- ^ Gray, Thomas (2000). English lyrics from Dryden to Burns. Elibron. pp. 155–56. ISBN 978-1-4021-0064-2.

- ^ Gayley, Charles Mills; Young, Clement C. (2005). English Poetry (Reprint ed.). Kessinger Publishing. p. lxxxv. ISBN 978-1-4179-0086-2.

- ^ Kuiper, Kathleen, ed. (2011). Poetry and drama literary terms and concepts. Britannica Educational Pub. in association with Rosen Educational Services. p. 51. ISBN 978-1-61530-539-1.

- ^ Campo, Juan E. (2009). Encyclopedia of Islam. Infobase. p. 260. ISBN 978-0-8160-5454-1.

- ^ Qureshi, Regula Burckhardt (Autumn 1990). «Musical Gesture and Extra-Musical Meaning: Words and Music in the Urdu Ghazal». Journal of the American Musicological Society. 43 (3): 457–97. doi:10.1525/jams.1990.43.3.03a00040.

- ^ Sequeira, Isaac (1 June 1981). «The Mystique of the Mushaira». The Journal of Popular Culture. 15 (1): 1–8. doi:10.1111/j.0022-3840.1981.4745121.x.

- ^ Schimmel, Annemarie (Spring 1988). «Mystical Poetry in Islam: The Case of Maulana Jalaladdin Rumi». Religion & Literature. 20 (1): 67–80.

- ^ Yarshater. Retrieved 25 July 2010.

- ^ Hafiz and the Place of Iranian Culture in the World Archived 3 May 2009 at the Wayback Machine by Aga Khan III, 9 November 1936 London.

- ^ Shamel, Shafiq (2013). Goethe and Hafiz. ISBN 978-3-0343-0881-6. Retrieved 29 October 2014.

- ^ «Goethe and Hafiz». Archived from the original on 29 October 2014. Retrieved 29 October 2014.

- ^ «GOETHE». Archived from the original on 5 September 2015. Retrieved 29 October 2014.

- ^ Chandler, Daniel. «Introduction to Genre Theory». Aberystwyth University. Archived from the original on 9 May 2015. Retrieved 10 December 2011.

- ^ Schafer, Jorgen; Gendolla, Peter, eds. (2010). Beyond the screen: transformations of literary structures, interfaces and genres. Verlag. pp. 16, 391–402. ISBN 978-3-8376-1258-5.

- ^ Kirk, G. S. (2010). Homer and the Oral Tradition (reprint ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 22–45. ISBN 978-0-521-13671-6.

- ^ Blasing, Mutlu Konuk (2006). Lyric poetry : the pain and the pleasure of words. Princeton University Press. pp. 1–22. ISBN 978-0-691-12682-1.

- ^ Hainsworth, J. B. (1989). Traditions of heroic and epic poetry. Modern Humanities Research Association. pp. 171–75. ISBN 978-0-947623-19-7.

- ^ «The Nobel Prize in Literature 1992: Derek Walcott». Swedish Academy. Retrieved 10 December 2011.

- ^ Dominik, William J.; Wehrle, T. (1999). Roman verse satire: Lucilius to Juvenal. Bolchazy-Carducci. pp. 1–3. ISBN 978-0-86516-442-0.

- ^ Black, Joseph, ed. (2011). Broadview Anthology of British Literature. Vol. 1. Broadview Press. p. 1056. ISBN 978-1-55481-048-2.

- ^ Pigman, G. W. (1985). Grief and English Renaissance elegy. Cambridge University Press. pp. 40–47. ISBN 978-0-521-26871-4.

- ^ Kennedy, David (2007). Elegy. Routledge. pp. 10–34. ISBN 978-1-134-20906-4.

- ^ Harpham, Geoffrey Galt; Abrams, M. H. (10 January 2011). A glossary of literary terms (10th ed.). Wadsworth Cengage Learning. p. 9. ISBN 978-0-495-89802-3.

- ^ Keith, Arthur Berriedale (1992). Sanskrit Drama in its origin, development, theory and practice. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 57–58. ISBN 978-81-208-0977-2.

- ^ Dolby, William (1983). «Early Chinese Plays and Theatre». In Mackerras, Colin (ed.). Chinese Theater: From Its Origins to the Present Day. University of Hawaii Press. p. 17. ISBN 978-0-8248-1220-1.

- ^ Giordano, Mathew (2004). Dramatic Poetics and American Poetic Culture, 1865–1904, Doctoral Dissertation. Columbus, Ohio: Ohio State.

Dramatic poetry: Pound’s ‘Sestina: Altaforte’ or Eliot’s ‘The Love Song of J. Alfred Proufrock’.

- ^ Eliot, T. S. (1951). «Poetry and Drama». tseliot.com. Retrieved 9 October 2020.

- ^ «The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock | Modern American Poetry». www.modernamericanpoetry.org. Retrieved 9 October 2020.

- ^ Allen, Mike (2005). Dutcher, Roger (ed.). The alchemy of stars. Science Fiction Poetry Association. pp. 11–17. ISBN 978-0-8095-1162-4.

- ^ Rombeck, Terry (22 January 2005). «Poe’s little-known science book reprinted». Lawrence Journal-World & News.

- ^ Robinson, Marilynne, «On Edgar Allan Poe», The New York Review of Books, vol. LXII, no. 2 (5 February 2015), pp. 4, 6.

- ^ Monte, Steven (2000). Invisible fences: prose poetry as a genre in French and American literature. University of Nebraska Press. pp. 4–9. ISBN 978-0-8032-3211-2.

- ^ «The Prose Poem: An International Journal«. Providence College. Retrieved 10 December 2011.

- ^ «Contemporary Haibun Online«. Retrieved 10 December 2011.

- ^ «Haibun Today: A Haibun & Tanka Prose Journal». haibuntoday.com.

- ^ «Honoring Marc Kelly Smith and International Poetry Slam Movement». Mary Hutchings Reed. Mary Hutchings Reed. Retrieved 5 May 2019.

- ^ «A Brief Guide to Slam Poetry». Academy of American Poets. Academy of American Poets. Retrieved 5 May 2019.

- ^ «5 Tips on Spoken Word». Power Poetry. Power Poetry. Retrieved 5 May 2019.

- ^ Wheeler, Lesley (2008). Voicing American Poetry: Sound and Performance from the 1920s to the Present. Cornell University Press. ISBN 9780801446689.

- ^ Seavon, Fernanda (March 2022). «INSTANTNÍ NOSTALGIE». A2 (5/2022): 11.

- ^ Bigsby, Christopher W. (1985). A Critical Introduction to Twentieth-Century American Drama: Volume 3 Beyond Broadway. Cambridge University Press. p. 45. ISBN 9780521278966. Retrieved 5 September 2012.

- ^ Gironès, Cristina (16 February 2022). «Object Paradise, el colectivo artístico que quiere devolver la vida y la voz al barrio de Žižkov». Radio Prague International. Radio Prague International. Retrieved 21 March 2022.

- ^ «obtydeník živé literatury». Tvar (7). July 2022. Retrieved 2 June 2022.

Bibliography[edit]

- Adams, Stephen J. (1997). Poetic designs: an introduction to meters, verse forms and figures of speech. Broadview. ISBN 978-1-55111-129-2.

- Corn, Alfred (1997). The Poem’s Heartbeat: A Manual of Prosody. Storyline Press. ISBN 978-1-885266-40-8.

- Fussell, Paul (1965). Poetic Meter and Poetic Form. Random House.

- Hollander, John (1981). Rhyme’s Reason. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-02740-2.

- Pinsky, Robert (1998). The Sounds of Poetry. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. ISBN 978-0-374-26695-0.

Further reading[edit]

Wikiquote has quotations related to Poetry.

Wikisource has original works on the topic: Poetry

Look up poetry in Wiktionary, the free dictionary.

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Poetry.

- Brooks, Cleanth (1947). The Well Wrought Urn: Studies in the Structure of Poetry. Harcourt Brace & Company. ISBN 9780156957052.

- Finch, Annie (2011). A Poet’s Ear: A Handbook of Meter and Form. University of Michigan Press. ISBN 978-0-472-05066-6.

- Fry, Stephen (2007). The Ode Less Travelled: Unlocking the Poet Within. Arrow Books. ISBN 978-0-09-950934-9.

- Gosse, Edmund William (1911). «Verse» . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 27 (11th ed.). pp. 1041–1047.

- Pound, Ezra (1951). ABC of Reading. Faber.

- Preminger, Alex; Brogan, Terry V. F.; Warnke, Frank J., eds. (1993). The New Princeton Encyclopedia of Poetry and Poetics (3rd ed.). Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-02123-2.

- Poetry, Music and Narrative — The Science of Art.

- Tatarkiewicz, Władysław, «The Concept of Poetry», Dialectics and Humanism: The Polish Philosophical Quarterly, vol. II, no. 2 (spring 1975), pp. 13–24.

Anthologies[edit]

- Ferguson, Margaret; Salter, Mary Jo; Stallworthy, Jon, eds. (1996). The Norton Anthology of Poetry (4th ed.). W.W. Norton & Co. ISBN 978-0-393-96820-0.

- Gardner, Helen, ed. (1972). New Oxford Book of English Verse 1250–1950. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-812136-7.

- Larkin, Philip, ed. (1973). The Oxford Book of Twentieth Century English Verse. Oxford University Press.