Всего найдено: 44

Добрый день!

Не нашла ответа на свой вопрос по поиску.

Подскажите, пожалуйста, как пишется словосочетание «Лига Чемпионов»: Лига Чемпионов или Лига чемпионов или вообще лига чемпионов?

спасибо!

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Правильно: Лига чемпионов.

Подскажите, пожалуйста, насколько допустимо использование слов, где «эсперанто-» выступает в качестве своеобразного префикса, обозначающего отношение к эсперанто и ко всему, с ним связанному? В Орфографическом словаре приводятся слова «эсперанто-движение» и «эсперанто-ассоциация», но допустимы ли в целом такие формы, как «эсперанто-организация», «эсперанто-лига«, «эсперанто-среда», «эсперанто-литература», «эсперанто-традиции», «эсперанто-встреча» и т. п.? Есть ли общее правило/соображение, или же с каждым конкретным словом вопрос решается отдельным образом? Спасибо!

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Такая модель образования новых слов сегодня очень продуктивна, и ошибки здесь нет. Однако традиционны сочетания с примыканием и управлением: литература по эсперанто, движение эсперанто и т. д.

Здравствуйте!

В словарях на вашем портале есть слова «амбидекстр» и «лиганды». А каково их значение?

Благодарю!

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Амбидекстр – человек, который одинаково хорошо владеет и правой, и левой рукой (т. е. не является ни правшой, ни левшой). О лигандах см. здесь.

Скажите, как правильно в дательном падеже написать мужские фамилии Лигай и Раковец?

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Правильно: Лигаю, Раковецу (предпочтительно), Раковцу (допустимо).

Здравствуйте!

Скажите нужна ли запятая при перечислении «там есть и Кубок Уефа, и Лига Чемпионов»

Кубок Уефа и Лига Чемпионов — два разных футбольных турнира.

Спасибо.

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Запятая нужна. Аббревиатура УЕФА пишется прописными.

Скажите,пожалуйста, если название учебного заведения написать с заглавных букв , будет ли считаться за ошибку ?

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Дело в том, что в число «названий учебных заведений» входят разные типы наименований. Некоторые из них требуется писать (вернее, начинать) с прописной буквы — например, полные и краткие официальные названия высших учебных заведений: Московский государственный университет. В названиях общеобразовательных школ с прописной буквы пишутся только заключаемые в кавычки элементы условного наименования: средняя школа «Лига школ», школа «Интеллектуал» и т. д.

Скорых иллюзий питать не надо, ведь это дети со сложной судьбой, и не(И) хулиганить, не(И) сквернословить они враз не перестанут. Е или И? Спасибо за своевременный ответ.

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Правильно: ни хулиганить, ни сквернословить.

Следует ли в тексте брать в кавычки: 1) названия иностранных компаний на латинице, 2) иностранные слова (напр., к»облигации («bonds») представляют собой…», 3) слова после оборота «так называемый/ая/ые»)? Спасибо.

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Все названные Вами условия не являются достаточными для использования кавычек.

Скажите, пожалуйста, в случае если выражение «и т. п.» следует за чередой однородных членов, соединенных повторяющимися союзами «и», ставится ли запятая перед «и т. п.»? Например: На сегодняшний день самыми надежными являются вложения денег в государственные ценные бумаги: и в казначейские облигации, и в облигации государственного займа (,) и т. п.

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Запятая не ставится перед и т. п., даже если И повторяющийся.

Уважаемая Грамота! Пожалуйста, ответьте: Высшая лига, Премьер-лига — так верно?

И еще: возможно ли написание информ-бюро?

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

1. Все верно. 2. Правильно слитное написание: информбюро.

Что означает выражение — Аннуитетный платеж

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Аннуитеты (от ср.-век. лат. annuitas — ежегодный платеж) — 1) ежегодные выплаты ренты по облигациям долгосрочных гос. займов; 2) сами гос. долгосрочные займы, по которым кредитор ежегодно получает определенный доход (ренту), устанавливаемый с расчетом на постепенное погашение капитальной суммы долга вместе с процентами по нему. В настоящее время не практикуются; 3) в Великобритании и других англоязычных странах — ежегодные выплаты разных видов, в т. ч. ренты, процентов и т. п.

Здравствуйте. Чтобы задать вам вопрос, пришлось опять регистрироваться (я уже делала это год назад). Такое нововведение для всех зарегистрированных пользователей или мне так «повезло»? Теперь вопрос.Нужна ли запятая перед как в этом предложении: Политики ведут себя (.) как хулиганствующие подростки. Чем объясняется постановка или отсутствие запятой в подобных конструкциях?

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Запятая не нужна, поскольку в подобных примерах сказуемое не имеет законченного смысла без сравнительного оборота.

На съезде присутствовал(и) 117 делигатов, причем большинство их был(и) представителями отдельных районов. И или О -почему?

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Предпочтительна форма единственного числа (пассивность подлежащего). Подробнее см. в Письмовнике.

Дорогое «Справочное бюро»!

Нужно ОЧЕНЬ СРОЧНО (газета)! Пожалуйста, скажите, как правильно писать, судя по всему, не зафиксированное в словарях, слово: «легалайз» или «лигалайз»? Отталкиваться от русского «легализация» или от транскрибированного и, соответственно, произносимого через «и» legalise?

Спасибо!

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Судя по практике употребления в Сети, через _и_ пишется название музыкальной группы, а через _е_ — слово, связанное с глаголом _легализовать_. Однако если есть возможность заменить это слово русским синонимом, лучше так и сделать. Если такой возможности нет, это слово стоит писать в кавычках.

Как правильно писать название российская футбольная премьер Лига? Спасибо

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Правильно: _Российская футбольная премьер-лига_.

|

|

| Organising body | UEFA |

|---|---|

| Founded | 1955; 68 years ago (rebranded in 1992) |

| Region | Europe |

| Number of teams |

|

| Qualifier for |

|

| Related competitions |

|

| Current champions | |

| Most successful club(s) | |

| Television broadcasters | List of broadcasters |

| Website | uefa.com/uefachampionsleague |

The UEFA Champions League (abbreviated as UCL, or sometimes, UEFA CL) is an annual club football competition organised by the Union of European Football Associations (UEFA) and contested by top-division European clubs, deciding the competition winners through a round robin group stage to qualify for a double-legged knockout format, and a single leg final. It is one of the most prestigious football tournaments in the world and the most prestigious club competition in European football, played by the national league champions (and, for some nations, one or more runners-up) of their national associations.

Introduced in 1955 as the Coupe des Clubs Champions Européens (French for European Champion Clubs’ Cup), and commonly known as the European Cup, it was initially a straight knockout tournament open only to the champions of Europe’s domestic leagues, with its winner reckoned as the European club champion. The competition took on its current name in 1992, adding a round-robin group stage in 1991 and allowing multiple entrants from certain countries since the 1997–98 season.[1] It has since been expanded, and while most of Europe’s national leagues can still only enter their champion, the strongest leagues now provide up to four teams.[2][3] Clubs that finish next-in-line in their national league, having not qualified for the Champions League, are eligible for the second-tier UEFA Europa League competition, and since 2021, for the third-tier UEFA Europa Conference League.[4]

In its present format, the Champions League begins in late June with a preliminary round, three qualifying rounds and a play-off round, all played over two legs. The six surviving teams enter the group stage, joining 26 teams qualified in advance. The 32 teams are drawn into eight groups of four teams and play each other in a double round-robin system. The eight group winners and eight runners-up proceed to the knockout phase that culminates with the final match in late May or early June.[5] The winner of the Champions League qualifies for the following year’s Champions League, the UEFA Super Cup, and the FIFA Club World Cup.[6][7]

Spanish clubs have the highest number of victories (19 wins), followed by England (14 wins) and Italy (12 wins). England has the largest number of winning teams, with five clubs having won the title. The competition has been won by 22 clubs, 13 of which have won it more than once, and eight successfully defended their title.[8] Real Madrid is the most successful club in the tournament’s history, having won it 14 times, including the first five seasons and also five of the last nine.[9] Only one club has won all of their matches in a single tournament en route to the tournament victory: Bayern Munich in the 2019–20 season.[10] Real Madrid are the current European champions, having beaten Liverpool 1–0 in the 2022 final.

History

| European Cup | |

|---|---|

| Season | Winners |

| 1955–56 | |

| 1956–57 | |

| 1957–58 | |

| 1958–59 | |

| 1959–60 | |

| 1960–61 | |

| 1961–62 | |

| 1962–63 | |

| 1963–64 | |

| 1964–65 | |

| 1965–66 | |

| 1966–67 | |

| 1967–68 | |

| 1968–69 | |

| 1969–70 | |

| 1970–71 | |

| 1971–72 | |

| 1972–73 | |

| 1973–74 | |

| 1974–75 | |

| 1975–76 | |

| 1976–77 | |

| 1977–78 | |

| 1978–79 | |

| 1979–80 | |

| 1980–81 | |

| 1981–82 | |

| 1982–83 | |

| 1983–84 | |

| 1984–85 | |

| 1985–86 | |

| 1986–87 | |

| 1987–88 | |

| 1988–89 | |

| 1989–90 | |

| 1990–91 | |

| 1991–92 | |

| UEFA Champions League | |

| 1992–93 | |

| 1993–94 | |

| 1994–95 | |

| 1995–96 | |

| 1996–97 | |

| 1997–98 | |

| 1998–99 | |

| 1999–2000 | |

| 2000–01 | |

| 2001–02 | |

| 2002–03 | |

| 2003–04 | |

| 2004–05 | |

| 2005–06 | |

| 2006–07 | |

| 2007–08 | |

| 2008–09 | |

| 2009–10 | |

| 2010–11 | |

| 2011–12 | |

| 2012–13 | |

| 2013–14 | |

| 2014–15 | |

| 2015–16 | |

| 2016–17 | |

| 2017–18 | |

| 2018–19 | |

| 2019–20 | |

| 2020–21 | |

| 2021–22 | |

| 2022–23 |

The first time the champions of two European leagues met was in what was nicknamed the 1895 World Championship, when English champions Sunderland beat Scottish champions Hearts 5–3.[11] The first pan-European tournament was the Challenge Cup, a competition between clubs in the Austro-Hungarian Empire.[12] Three years later, in 1900, the champions of Belgium, Netherlands and Switzerland, which were the only existing leagues in continental Europe at the time, participated in the Coupe Van der Straeten Ponthoz, thus being dubbed as the «club championship of the continent» by the local newspapers.[13][14]

The Mitropa Cup, a competition modelled after the Challenge Cup, was created in 1927, an idea of Austrian Hugo Meisl, and played between Central European clubs.[15] In 1930, the Coupe des Nations (French: Nations Cup), the first attempt to create a cup for national champion clubs of Europe, was played and organised by Swiss club Servette.[16] Held in Geneva, it brought together ten champions from across the continent. The tournament was won by Újpest of Hungary.[16] Latin European nations came together to form the Latin Cup in 1949.[17]

After receiving reports from his journalists over the highly successful South American Championship of Champions of 1948, Gabriel Hanot, editor of L’Équipe, began proposing the creation of a continent-wide tournament.[18] In interviews, Jacques Ferran (one of the founders of the European Champions Cup, together with Gabriel Hanot),[19] said that the South American Championship of Champions was the inspiration for the European Champions Cup.[20] After Stan Cullis declared Wolverhampton Wanderers «Champions of the World» following a successful run of friendlies in the 1950s, in particular a 3–2 friendly victory against Budapest Honvéd, Hanot finally managed to convince UEFA to put into practice such a tournament.[1] It was conceived in Paris in 1955 as the European Champion Clubs’ Cup.[1]

1955–1967: Beginnings

Alfredo Di Stéfano (pictured in 1959) led Real Madrid to five consecutive European Cup titles between 1956 and 1960.

The first European Cup took place during the 1955–56 season.[21][22] Sixteen teams participated (some by invitation): AC Milan (Italy), AGF Aarhus (Denmark), Anderlecht (Belgium), Djurgården (Sweden), Gwardia Warszawa (Poland), Hibernian (Scotland), Partizan (Yugoslavia), PSV Eindhoven (Netherlands), Rapid Wien (Austria), Real Madrid (Spain), Rot-Weiss Essen (West Germany), Saarbrücken (Saar), Servette (Switzerland), Sporting CP (Portugal), Stade de Reims (France), and Vörös Lobogó (Hungary).[21][22]

The first European Cup match took place on 4 September 1955, and ended in a 3–3 draw between Sporting CP and Partizan.[21][22] The first goal in European Cup history was scored by João Baptista Martins of Sporting CP.[21][22] The inaugural final took place at the Parc des Princes between Stade de Reims and Real Madrid on 13 June 1956.[21][22][23] The Spanish squad came back from behind to win 4–3 thanks to goals from Alfredo Di Stéfano and Marquitos, as well as two goals from Héctor Rial.[21][22][23] Real Madrid successfully defended the trophy next season in their home stadium, the Santiago Bernabéu, against Fiorentina.[24][25] After a scoreless first half, Real Madrid scored twice in six minutes to defeat the Italians.[23][24][25] In 1958, Milan failed to capitalise after going ahead on the scoreline twice, only for Real Madrid to equalise.[26][27] The final, held in Heysel Stadium, went to extra time where Francisco Gento scored the game-winning goal to allow Real Madrid to retain the title for the third consecutive season.[23][26][27]

In a rematch of the first final, Real Madrid faced Stade Reims at the Neckarstadion for the 1959 final, and won 2–0.[23][28][29] West German side Eintracht Frankfurt became the first non-Latin team to reach the European Cup final.[30][31] The 1960 final holds the record for the most goals scored, with Real Madrid beating Eintracht Frankfurt 7–3 in Hampden Park, courtesy of four goals by Ferenc Puskás and a hat-trick by Alfredo Di Stéfano.[23][30][31] This was Real Madrid’s fifth consecutive title, a record that still stands today.[8]

Real Madrid’s reign ended in the 1960–61 season when bitter rivals Barcelona dethroned them in the first round.[32][33] Barcelona were defeated in the final by Portuguese side Benfica 3–2 at Wankdorf Stadium.[32][33][34] Reinforced by Eusébio, Benfica defeated Real Madrid 5–3 at the Olympic Stadium in Amsterdam and kept the title for a second consecutive season.[34][35][36] Benfica wanted to repeat Real Madrid’s successful run of the 1950s after reaching the showpiece event of the 1962–63 European Cup, but a brace from Brazilian-Italian José Altafini at the Wembley Stadium gave the spoils to Milan, making the trophy leave the Iberian Peninsula for the first time ever.[37][38][39]

Inter Milan beat an ageing Real Madrid 3–1 in the Ernst-Happel-Stadion to win the 1963–64 season and replicate their local-rival’s success.[40][41][42] The title stayed in Milan for the third year in a row after Inter beat Benfica 1–0 at their home ground, the San Siro.[43][44][45] Under the leadership of Jock Stein, Scottish club Celtic beat Inter Milan 2–1 in the 1967 final to become the first British club to win the European Cup.[46][47] The Celtic players that day, all of whom were born within 30 miles (48 km) of Glasgow, subsequently became known as the «Lisbon Lions».[48]

1968–1978

Johan Cruyff (pictured in 1972) won the European Cup three times in a row with Ajax.

The 1967–68 season saw Manchester United become the first English team to win the European Cup, beating two-times winners Benfica 4–1 in the final.[49] This final came 10 years after the Munich air disaster, which had claimed the lives of eight United players and left their manager, Matt Busby, fighting for his life.[50] In the 1968–69 season, Ajax became the first Dutch team to reach the European Cup final, but they were beaten 4–1 by Milan, who claimed their second European Cup, with Pierino Prati scoring a hat-trick.[51]

The 1969–70 season saw the first Dutch winners of the competition. Feyenoord knocked out the defending champions, Milan in the second round,[52] before beating Celtic in the final.[53] In the 1970–71 season Ajax won the title, beating Greek side Panathinaikos in the final.[54] the season saw a number of changes, with penalty shoot-outs being introduced, and the away goals rule being changed so that it would be used in all rounds except the final.[55] It was also the first time a Greek team reached the final, as well as the first season that Real Madrid failed to qualify, having finished sixth in La Liga the previous season.[56] Ajax went on to win the competition three years in row (1971 to 1973), which Bayern Munich emulated from 1974 to 1976, before Liverpool won their first two titles in 1977 and 1978.[57]

Anthem

«Magic…it’s magic above all else. When you hear the anthem it captivates you straight away.»

—Zinedine Zidane[58]

The UEFA Champions League anthem, officially titled simply as «Champions League», was written by Tony Britten, and is an adaptation of George Frideric Handel’s 1727 anthem Zadok the Priest (one of his Coronation Anthems).[59][60] UEFA commissioned Britten in 1992 to arrange an anthem, and the piece was performed by London’s Royal Philharmonic Orchestra and sung by the Academy of St. Martin in the Fields.[59] Stating that «the anthem is now almost as iconic as the trophy», UEFA’s official website adds it is «known to set the hearts of many of the world’s top footballers aflutter».[59]

The two teams line up for the UEFA Champions League Anthem before each match and a flag of the Champions League «starball» logo is waved in the centre circle.

The chorus contains the three official languages used by UEFA: English, German, and French.[61] The climactic moment is set to the exclamations ‘Die Meister! Die Besten! Les Grandes Équipes! The Champions!’.[62] The anthem’s chorus is played before each UEFA Champions League game as the two teams are lined up, as well as at the beginning and end of television broadcasts of the matches. In addition to the anthem, there is also entrance music, which contains parts of the anthem itself, which is played as teams enter the field.[63] The complete anthem is about three minutes long, and has two short verses and the chorus.[61]

Special vocal versions have been performed live at the Champions League final with lyrics in other languages, changing over to the host nation’s language for the chorus. These versions were performed by Andrea Bocelli (Italian) (Rome 2009, Milan 2016 and Cardiff 2017), Juan Diego Flores (Spanish) (Madrid 2010), All Angels (Wembley 2011), Jonas Kaufmann and David Garrett (Munich 2012), and Mariza (Lisbon 2014). In the 2013 final at Wembley Stadium, the chorus was played twice. In the 2018 and 2019 finals, held in Kyiv and Madrid respectively, the instrumental version of the chorus was played, by 2Cellos (2018) and Asturia Girls (2019).[64][65] The anthem has been released commercially in its original version on iTunes and Spotify with the title of Champions League Theme. In 2018, composer Hans Zimmer remixed the anthem with rapper Vince Staples for EA Sports’ video game FIFA 19, with it also featuring in the game’s reveal trailer.[66]

Branding

The «starball» logo is incorporated into the design of the competition’s official match ball, the Adidas Finale.

In 1991, UEFA asked its commercial partner, Television Event and Media Marketing (TEAM), to help brand the Champions League. This resulted in the anthem, «house colours» of black and white or silver and a logo, and the «starball». The starball was created by Design Bridge, a London-based firm selected by TEAM after a competition.[67] TEAM gives particular attention to detail in how the colours and starball are depicted at matches. According to TEAM, «Irrespective of whether you are a spectator in Moscow or Milan, you will always see the same stadium dressing materials, the same opening ceremony featuring the ‘starball’ centre circle ceremony, and hear the same UEFA Champions League Anthem». Based on research it conducted, TEAM concluded that by 1999, «the starball logo had achieved a recognition rate of 94 percent among fans».[68]

Format

Qualification

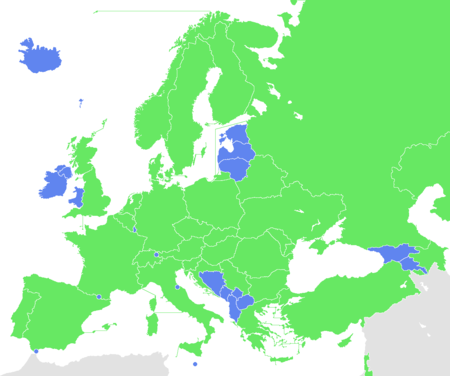

A map of UEFA countries whose teams have reached the group stage of the UEFA Champions League

UEFA member state that has been represented in the group stage

UEFA member state that has not been represented in the group stage

The UEFA Champions League begins with a double round-robin group stage of 32 teams, which since the 2009–10 season is preceded by two qualification ‘streams’ for teams that do not receive direct entry to the tournament proper. The two streams are divided between teams qualified by virtue of being league champions, and those qualified by virtue of finishing second or third in their national championship.

The number of teams that each association enters into the UEFA Champions League is based upon the UEFA coefficients of the member associations. These coefficients are generated by the results of clubs representing each association during the previous five Champions League and UEFA Cup/Europa League seasons. The higher an association’s coefficient, the more teams represent the association in the Champions League, and the fewer qualification rounds the association’s teams must compete in.

Four of the remaining six qualifying places are granted to the winners of a six-round qualifying tournament between the remaining 43 or 44 national champions, within which those champions from associations with higher coefficients receive byes to later rounds. The other two are granted to the winners of a three-round qualifying tournament between 10–11 clubs from the associations ranked 5–6 through 15, which have qualified based upon finishing second or third in their respective national league.

In addition to sporting criteria, any club must be licensed by its national association to participate in the Champions League. To obtain a license, the club must meet certain stadium, infrastructure and finance requirements.

In 2005–06, Liverpool and Artmedia Bratislava became the first teams to reach the Champions League group stage after playing in all three qualifying rounds. Real Madrid and Barcelona hold the record for the most appearances in the group stage, having qualified 25 times, followed by FC Porto and Bayern Munich on 24.[69]

Between 1999 and 2008, no differentiation was made between champions and non-champions in qualification. The 16 top-ranked teams spread across the biggest domestic leagues qualified directly for the tournament group stage. Prior to this, three preliminary knockout qualifying rounds whittled down the remaining teams, with teams starting in different rounds.

An exception to the usual European qualification system happened in 2005, after Liverpool won the Champions League the year before, but did not finish in a Champions League qualification place in the Premier League that season. UEFA gave special dispensation for Liverpool to enter the Champions League, giving England five qualifiers.[70] UEFA subsequently ruled that the defending champions qualify for the competition the following year regardless of their domestic league placing. However, for those leagues with four entrants in the Champions League, this meant that, if the Champions League winner fell outside of its domestic league’s top four, it would qualify at the expense of the fourth-placed team in the league. Until 2015–16, no association could have more than four entrants in the Champions League.[71] In May 2012, Tottenham Hotspur finished fourth in the 2011–12 Premier League, two places ahead of Chelsea, but failed to qualify for the 2012–13 Champions League, after Chelsea won the 2012 final.[72] Tottenham were demoted to the 2012–13 UEFA Europa League.[72]

In May 2013,[73] it was decided that, starting from the 2015–16 season (and continuing at least for the three-year cycle until the 2017–18 season), the winners of the previous season’s UEFA Europa League would qualify for the UEFA Champions League, entering at least the play-off round, and entering the group stage if the berth reserved for the Champions League title holders was not used. The previous limit of a maximum of four teams per association was increased to five, meaning that a fourth-placed team from one of the top three ranked associations would only have to be moved to the Europa League if both the Champions League and Europa League winners came from that association and both finished outside the top four of their domestic league.[74]

In 2007, Michel Platini, the UEFA president, had proposed taking one place from the three leagues with four entrants and allocating it to that nation’s cup winners. This proposal was rejected in a vote at a UEFA Strategy Council meeting.[75] In the same meeting, however, it was agreed that the third-placed team in the top three leagues would receive automatic qualification for the group stage, rather than entry into the third qualifying round, while the fourth-placed team would enter the play-off round for non-champions, guaranteeing an opponent from one of the top 15 leagues in Europe. This was part of Platini’s plan to increase the number of teams qualifying directly into the group stage, while simultaneously increasing the number of teams from lower-ranked nations in the group stage.[76]

In 2012, Arsène Wenger referred to qualifying for the Champions League by finishing in the top four places in the English Premier League as the «4th Place Trophy». The phrase was coined after a pre-match conference when he was questioned about Arsenal’s lack of a trophy after exiting the FA Cup. He said «The first trophy is to finish in the top four».[77] At Arsenal’s 2012 AGM, Wenger was also quoted as saying: «For me there are five trophies every season: Premier League, Champions League, the third is to qualify for the Champions League…»[78]

Group stage and knockout phase

The tournament proper begins with a group stage of 32 teams, divided into eight groups of four.[79] The draw to determine which teams go into each group is seeded based on teams’ performance in UEFA competitions, and no group may contain more than one club from each nation. Each team plays six group stage games, meeting the other three teams in its group home and away in a round-robin format.[79] The winning team and the runners-up from each group then progress to the next round. The third-placed team enters the UEFA Europa League.

For the next stage – the last 16 – the winning team from one group plays against the runners-up from another group, and teams from the same association may not be drawn against each other. From the quarter-finals onwards, the draw is entirely random, without association protection.[80]

The group stage is played from September to December, whilst the knock-out stage starts in February. The knock-out ties are played in a two-legged format, with the exception of the final. The final is typically held in the last two weeks of May, or in the early days of June, which has happened in three consecutive odd-numbered years since 2015. In the 2019–20 season, due to the COVID-19 pandemic the tournament was suspended for five months. The format of the remainder of the tournament was temporarily amended as a result, with the quarter-finals and semi-finals being played as single match knockout ties at neutral venues in Lisbon, Portugal in the summer with the final taking place on 23 August.[81]

Distribution

The following is the default access list.[82][83]

| Teams entering in this round | Teams advancing from the previous round | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Preliminary round (4 teams) |

|

||

| First qualifying round (34 teams) |

|

|

|

| Second qualifying round | Champions Path (20 teams) |

|

|

| League Path (6 teams) |

|

||

| Third qualifying round | Champions Path (12 teams) |

|

|

| League Path (8 teams) |

|

|

|

| Play-off round | Champions Path (8 teams) |

|

|

| League Path (4 teams) |

|

||

| Group stage (32 teams) |

|

|

|

| Knockout phase (16 teams) |

|

Changes will be made to the access list above if the Champions League or Europa League title holders qualify for the tournament via their domestic leagues.

- If the Champions League title holders qualify for the group stage via their domestic league, the champions of association 11 enters the group stage, and champions of the highest-ranked associations in earlier rounds are also promoted accordingly.

- If the Europa League title holders qualify for the group stage via their domestic league, the third-placed team of association 5 enter the group stage, and runners-up of the highest-ranked associations in the second qualifying round are also promoted accordingly.

- If the Champions League or Europa League title holders qualify for the qualifying rounds via their domestic league, their spot in the qualifying rounds is vacated, and teams of the highest-ranked associations in earlier rounds are promoted accordingly.

- An association may have a maximum of five teams in the Champions League.[82] Therefore, if both the Champions League and Europa League title holders come from the same top-four association and finish outside of the top four of their domestic league, the fourth-placed team of the league will not compete in the Champions League and will instead compete in the Europa League.

Prizes

Trophy and medals

Each year, the winning team is presented with the European Champion Clubs’ Cup, the current version of which has been awarded since 1967. From the 1968–69 season and prior to the 2008–09 season any team that won the Champions League three years in a row or five times overall was awarded the official trophy permanently.[84] Each time a club achieved this, a new official trophy had to be forged for the following season.[85] Five clubs own a version of the official trophy: Real Madrid, Ajax, Bayern Munich, Milan and Liverpool.[84] Since 2008, the official trophy has remained with UEFA and the clubs are awarded a replica.[84]

The current trophy is 74 cm (29 in) tall and made of silver, weighing 11 kg (24 lb). It was designed by Jürg Stadelmann, a jeweller from Bern, Switzerland, after the original was given to Real Madrid in 1966 in recognition of their six titles to date, and cost 10,000 Swiss francs.

As of the 2012–13 season, 40 gold medals are presented to the Champions League winners, and 40 silver medals to the runners-up.[86]

Prize money

As of 2021–22, the fixed amount of prize money paid to participating clubs is as follows.[87]

- Play-off round: €5,000,000

- Base fee for group stage: €15,640,000

- Group match victory: €2,800,000

- Group match draw: €900,000

- Round of 16: €9,600,000

- Quarter-finals: €10,600,000

- Semi-finals: €12,500,000

- Runners-up: €15,500,000

- Champions: €20,000,000

This means that, at best, a club can earn €85,140,000 of prize money under this structure, not counting shares of the qualifying rounds, play-off round or the market pool.

A large part of the distributed revenue from the UEFA Champions League is linked to the «market pool», the distribution of which is determined by the value of the television market in each nation. For the 2014–15 season, Juventus, who were the runners-up, earned nearly €89.1 million in total, of which €30.9 million was prize money, compared with the €61.0 million earned by Barcelona, who won the tournament and were awarded €36.4 million in prize money.[88]

Real Madrid were barred from wearing their bwin-sponsored jerseys when they played against Galatasaray in Turkey in April 2013, where gambling advertisements are banned.

Like the FIFA World Cup, the UEFA Champions League is sponsored by a group of multinational corporations, in contrast to the single main sponsor typically found in national top-flight leagues. When the Champions League was created in 1992, it was decided that a maximum of eight companies should be allowed to sponsor the event, with each corporation being allocated four advertising boards around the perimeter of the pitch, as well as logo placement at pre- and post-match interviews and a certain number of tickets to each match. This, combined with a deal to ensure tournament sponsors were given priority on television advertisements during matches, ensured that each of the tournament’s main sponsors was given maximum exposure.[89]

From the 2012–13 knockout phase, UEFA used LED advertising hoardings installed in knock-out participant stadiums, including the final stage. From the 2015–16 season onwards, UEFA has used such hoardings from the play-off round until the final.[90]

The tournament’s main sponsors for the 2021–24 cycle are:

- Oppo[91]

- FedEx[92]

- Turkish Airlines[93]

- Heineken N.V.[94]

- Heineken (except Albania, Azerbaijan, Bosnia and Herzegovina, France, Kazakhstan, Kosovo, Norway and Turkey)

- Heineken Silver

- Heineken (except Albania, Azerbaijan, Bosnia and Herzegovina, France, Kazakhstan, Kosovo, Norway and Turkey)

- Just Eat Takeaway[95]

- 10bis (Israel only)

- Menulog (Australasia only)

- Bistro (Slovakia only)

- Just Eat

- Denmark

- France

- Ireland

- Italy

- Spain

- Switzerland

- United Kingdom

- Lieferando (Germany and Austria only)

- Pyszne (Poland only)

- Grubhub and Seamless (United States only)

- SkipTheDishes (Canada only)

- Takeaway (Belgium, Bulgaria and Luxembourg only)

- Thuisbezorgd (Netherlands only)

- Mastercard[96]

- PepsiCo[97]

- Pepsi

- Pepsi Max

- Lay’s (except Australasia, Balkan states, Turkey, Ireland and the United Kingdom)

- Smith’s (Australasia only)

- Walkers (United Kingdom and Ireland only)

- Ruffles (Turkey only)

- Chipsy (Croatia, Albania, Serbia, Montenegro, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Kosovo and North Macedonia only)

- Rockstar[98]

- Sony[99]

- PlayStation 5

- Socios.com (United States only)[100]

Adidas is a secondary sponsor and supplies the official match ball, the Adidas Finale, and Macron supplies the referees’ kit.[101] Hublot is also a secondary sponsor as the official fourth official board of the competition.[102]

Individual clubs may wear jerseys with advertising. However, only two sponsorships are permitted per jersey in addition to that of the kit manufacturer, at the chest and the left sleeve.[103] Exceptions are made for non-profit organisations, which can feature on the front of the shirt, incorporated with the main sponsor or in place of it; or on the back, either below the squad number or on the collar area.[104]

If a club plays a match in a nation where the relevant sponsorship category is restricted (such as France’s alcohol advertising restriction), then they must remove that logo from their jerseys. For example, when Rangers played French side Auxerre in the 1996–97 Champions League, they wore the logo of Center Parcs instead of McEwan’s Lager (both companies at the time were subsidiaries of Scottish & Newcastle).[105]

Media coverage

The competition attracts an extensive television audience, not just in Europe, but throughout the world. The final of the tournament has been, in recent years, the most-watched annual sporting event in the world.[106] The final of the 2012–13 tournament had the competition’s highest TV ratings to date, drawing approximately 360 million television viewers.[107]

Team records and statistics

Performances by club

Performances by nation

Notes

- ^ Includes clubs representing West Germany. No clubs representing East Germany appeared in a final.

- ^ Both Yugoslav final appearances were by clubs from SR Serbia

Player records

Most wins

| No. of wins | Player | Club(s) |

|---|---|---|

| 6 | Francisco Gento | Real Madrid (1956, 1957, 1958, 1959, 1960, 1966) |

| 5 | Juan Alonso | Real Madrid (1956, 1957, 1958, 1959, 1960) |

| Rafael Lesmes | ||

| Marquitos | ||

| Héctor Rial | ||

| Alfredo Di Stéfano | ||

| José María Zárraga | ||

| Alessandro Costacurta | AC Milan (1989, 1990, 1994, 2003, 2007) | |

| Paolo Maldini | ||

| Cristiano Ronaldo | Manchester United (2008) Real Madrid (2014, 2016, 2017, 2018) |

|

| Toni Kroos | Bayern Munich (2013) Real Madrid (2016, 2017, 2018, 2022) |

|

| Gareth Bale | Real Madrid (2014, 2016, 2017, 2018, 2022) | |

| Karim Benzema | ||

| Dani Carvajal | ||

| Casemiro | ||

| Isco | ||

| Marcelo | ||

| Luka Modrić | ||

| Nacho | ||

| 4 | Joseíto | Real Madrid (1956, 1957, 1958, 1959) |

| Enrique Mateos | Real Madrid (1957, 1958, 1959, 1960) | |

| Juan Santisteban | ||

| José Santamaría | Real Madrid (1958, 1959, 1960, 1966) | |

| Phil Neal | Liverpool (1977, 1978, 1981, 1984) | |

| Clarence Seedorf | Ajax (1995) Real Madrid (1998) AC Milan (2003, 2007) |

|

| Samuel Eto’o | Real Madrid (2000) Barcelona (2006, 2009) Inter Milan (2010) |

|

| Andrés Iniesta | Barcelona (2006, 2009, 2011, 2015) | |

| Lionel Messi | ||

| Xavi | ||

| Gerard Piqué | Manchester United (2008) Barcelona (2009, 2011, 2015) |

|

| Sergio Ramos | Real Madrid (2014, 2016, 2017, 2018) | |

| Raphaël Varane | ||

| Mateo Kovačić | Real Madrid (2016, 2017, 2018) Chelsea (2021) |

|

| Lucas Vázquez | Real Madrid (2016, 2017, 2018, 2022) |

Most appearances

- As of 2 November 2022[108][109][110]

Players that are still active in Europe are highlighted in boldface.

The table below does not include appearances made in the qualification stage of the competition.

Most goals

- As of 2 November 2022[111][112][113]

- A

indicates the player was from the European Cup era.

- Players that are taking part in the 2022–23 UEFA Champions League are highlighted in boldface.

- The table below does not include goals scored in the qualification stage of the competition.

Awards

Starting from the 2021–22 edition, UEFA introduced the UEFA Champions League Player of the Season award.

The jury is composed of the coaches of the clubs that participated in the group stage of the competition, as well as 55 journalists selected by the European Sports Media (ESM) group, one from each UEFA member association.

Winners

| Season | Player | Club |

|---|---|---|

| UEFA Champions League Player of the Season | ||

| 2021–22 |

In the same season, UEFA also introduced the UEFA Champions League Young Player of the Season award.

Winners

| Season | Player | Club |

|---|---|---|

| UEFA Champions League Young Player of the Season | ||

| 2021–22 |

See also

- Continental football championships

- List of association football competitions

References

- ^ a b c «Football’s premier club competition». UEFA. 31 January 2010. Archived from the original on 15 February 2010. Retrieved 23 May 2010.

- ^ «Clubs». UEFA. 12 May 2020. Retrieved 12 May 2020.

- ^ «UEFA Europa League further strengthened for 2015–18 cycle» (Press release). UEFA. 24 May 2013. Retrieved 2 August 2013.

- ^ «UEFA Executive Committee approves new club competition» (Press release). UEFA. 2 December 2018. Archived from the original on 2 December 2018. Retrieved 2 December 2018.

- ^ «Matches». UEFA. Retrieved 12 May 2020.

- ^ «Club competition winners do battle». UEFA. 31 January 2010. Archived from the original on 1 July 2010. Retrieved 23 May 2010.

- ^ «FIFA Club World Cup». FIFA. Archived from the original on 11 October 2007. Retrieved 30 December 2013.

- ^ a b «European Champions’ Cup». Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation. 31 January 2010. Retrieved 23 May 2010.

- ^ «Most titles | History». UEFA. Retrieved 29 May 2022.

- ^ «A perfect 11! Flawless Bayern set new Champions League record with PSG victory». Goal.com. Retrieved 2 August 2021.

- ^ «When Sunderland met Hearts in the first ever ‘Champions League’ match». Nutmeg Magazine. 2 September 2019. Archived from the original on 13 July 2020.

- ^ García, Javier; Kutschera, Ambrosius; Schöggl, Hans; Stokkermans, Karel (2009). «Austria/Habsburg Monarchy – Challenge Cup 1897–1911». Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation. Retrieved 5 September 2011.

- ^ «European Cup Origins». europeancuphistory.com. Archived from the original on 5 November 2021. Retrieved 13 July 2022.

- ^ «Coupe Van der Straeten Ponthoz». RSSSF. 10 February 2022. Archived from the original on 9 July 2022. Retrieved 13 July 2022.

- ^ Stokkermans, Karel (2009). «Mitropa Cup». Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation.

- ^ a b Ceulemans, Bart; Michiel, Zandbelt (2009). «Coupe des Nations 1930». Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation. Retrieved 5 September 2011.

- ^ Stokkermans, Karel; Gorgazzi, Osvaldo José (2006). «Latin Cup». Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation. Retrieved 5 September 2011.

- ^ «Primeira Libertadores – História (Globo Esporte 09/02/20.l.08)». Youtube.com. Archived from the original on 11 December 2021. Retrieved 14 August 2010.

- ^ «European Cup pioneer Jacques Ferran passes away». UEFA. 8 February 2019. Retrieved 1 January 2021.

- ^ «Globo Esporte TV programme, Brazil, broadcast (in Portuguese) on 10/05/2015: Especial: Liga dos Campeões completa 60 anos, e Neymar ajuda a contar essa história. Accessed on 06/12/2015. Ferran’s speech goes from 5:02 to 6:51 in the video». Archived from the original on 4 March 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f «1955/56 European Champions Clubs’ Cup». Union of European Football Associations. 31 January 2010. Archived from the original on 24 September 2011. Retrieved 23 May 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f «European Champions’ Cup 1955–56 – Details». Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation. 31 January 2010. Retrieved 23 May 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f «Trofeos de Fútbol». Real Madrid. 31 January 2010. Archived from the original on 3 October 2009. Retrieved 23 May 2010.

- ^ a b «1956/57 European Champions Clubs’ Cup». Union of European Football Associations. 31 January 2010. Archived from the original on 24 September 2011. Retrieved 23 May 2010.

- ^ a b «Champions’ Cup 1956–57». Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation. 31 January 2010. Retrieved 23 May 2010.

- ^ a b «1957/58 European Champions Clubs’ Cup». Union of European Football Associations. 31 January 2010. Archived from the original on 24 September 2011. Retrieved 23 May 2010.

- ^ a b «Champions’ Cup 1957–58». Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation. 31 January 2010. Retrieved 23 May 2010.

- ^ «1958/59 European Champions Clubs’ Cup». Union of European Football Associations. 31 January 2010. Archived from the original on 17 September 2011. Retrieved 23 May 2010.

- ^ «Champions’ Cup 1958–59». Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation. 31 January 2010. Retrieved 23 May 2010.

- ^ a b «1959/60 European Champions Clubs’ Cup». Union of European Football Associations. 31 January 2010. Archived from the original on 24 September 2011. Retrieved 23 May 2010.

- ^ a b «Champions’ Cup 1959–60». Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation. 31 January 2010. Retrieved 23 May 2010.

- ^ a b «1960/61 European Champions Clubs’ Cup». Union of European Football Associations. 31 January 2010. Archived from the original on 24 September 2011. Retrieved 23 May 2010.

- ^ a b «Champions’ Cup 1960–61». Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation. 31 January 2010. Retrieved 23 May 2010.

- ^ a b «Anos 60: A «década de ouro»«. Sport Lisboa e Benfica. 31 January 2010. Archived from the original on 5 October 2007. Retrieved 23 May 2010.

- ^ «1961/62 European Champions Clubs’ Cup». Union of European Football Associations. 31 January 2010. Archived from the original on 24 September 2011. Retrieved 23 May 2010.

- ^ «Champions’ Cup 1961–62». Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation. 31 January 2010. Retrieved 23 May 2010.

- ^ «1962/63 European Champions Clubs’ Cup». Union of European Football Associations. 31 January 2010. Archived from the original on 24 September 2011. Retrieved 23 May 2010.

- ^ «Champions’ Cup 1962–63». Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation. 31 January 2010. Retrieved 23 May 2010.

- ^ «Coppa Campioni 1962/63». Associazione Calcio Milan. 31 January 2010. Archived from the original on 5 April 2011. Retrieved 23 May 2010.

- ^ «1963/64 European Champions Clubs’ Cup». Union of European Football Associations. 31 January 2010. Archived from the original on 24 September 2011. Retrieved 23 May 2010.

- ^ «Champions’ Cup 1963–64». Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation. 31 January 2010. Retrieved 23 May 2010.

- ^ «Palmares: Prima coppa dei campioni – 1963/64» (in Italian). FC Internazionale Milano. 31 January 2010. Archived from the original on 18 May 2006. Retrieved 23 May 2010.

- ^ «1964/65 European Champions Clubs’ Cup». Union of European Football Associations. 31 January 2010. Archived from the original on 18 September 2011. Retrieved 23 May 2010.

- ^ «Champions’ Cup 1964–65». Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation. 31 January 2010. Retrieved 23 May 2010.

- ^ «Palmares: Prima coppa dei campioni – 1964/65» (in Italian). FC Internazionale Milano. 31 January 2010. Archived from the original on 18 May 2006. Retrieved 23 May 2010.

- ^ «A Sporting Nation – Celtic win European Cup 1967». BBC Scotland. Archived from the original on 9 December 2006. Retrieved 28 January 2016.

- ^ «Celtic immersed in history before UEFA Cup final». Sports Illustrated. 20 May 2003. Archived from the original on 11 January 2012. Retrieved 15 May 2010.

- ^ Lennox, Doug (2009). Now You Know Soccer. Dundurn Press. p. 143. ISBN 978-1-55488-416-2.

now you know soccer who were the lisbon lions.

- ^ «Man. United – Benfica 1967 History | UEFA Champions League». UEFA.com. Union of European Football Associations. Retrieved 20 June 2020.

- ^ «Season 1967». UEFA.com. Union of European Football Associations. Retrieved 20 June 2020.

- ^ «Milan-Ajax 1968 History». UEFA.com. Union of European Football Associations. Retrieved 2 July 2020.

- ^ «Feyenoord – Milan 1969 History | UEFA Champions League». UEFA.com. Union of European Football Associations. Retrieved 12 August 2020.

- ^ «Feyenoord – Celtic 1969 History | UEFA Champions League». UEFA.com. Union of European Football Associations. Retrieved 12 August 2020.

- ^ «Ajax – Panathinaikos 1970 History | UEFA Champions League». UEFA.com. Union of European Football Associations. Retrieved 12 August 2020.

- ^ Zea, Antonio; Haisma, Marcel (9 January 2008). «European Champions’ Cup and Fairs’ Cup 1970–71 – Details». RSSSF. Retrieved 12 August 2020.

- ^ «Classification First Division 1969–70». bdfutbol.com. Retrieved 12 August 2020.

- ^ «Champions League final: Full list of all UCL and European Cup winners as Chelsea, Man City try to make history». CBS Sports. Retrieved 29 October 2021.

- ^ «The story of the UEFA Champions League anthem». Union of European Football Associations. Retrieved 17 August 2018 – via YouTube.

- ^ a b c «UEFA Champions League anthem». UEFA.com. Union of European Football Associations. Retrieved 12 May 2020.

- ^ Media, democracy and European culture. Intellect Books. 2009. p. 129. ISBN 9781841502472. Retrieved 14 September 2014.

- ^ a b «What is the Champions League music? The lyrics and history of one of football’s most famous songs». Wales Online. Retrieved 17 August 2018.

- ^ Fornäs, Johan (2012). Signifying Europe (PDF). Bristol, England: intellect. pp. 185–187. Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 February 2018.

- ^ «UEFA Champions League entrance music». Archived from the original on 11 December 2021. Retrieved 17 August 2018 – via YouTube.

- ^ «2Cellos to perform UEFA Champions League anthem in Kyiv». UEFA.com. Union of European Football Associations. 18 May 2018. Archived from the original on 25 May 2018. Retrieved 17 August 2018.

- ^ «Asturia Girls to perform UEFA Champions League anthem in Madrid». UEFA.com. Union of European Football Associations. 21 May 2019. Archived from the original on 23 May 2019. Retrieved 19 June 2019.

- ^ «Behind the Music: Champions League Anthem Remix with Hans Zimmer». Electronic Arts. 12 June 2018. Archived from the original on 28 June 2018. Retrieved 13 August 2018.

- ^ King, Anthony (2004). «The new symbols of European football». International Review for the Sociology of Sport. London; Thousand Oaks, CA; New Delhi. 39 (3).

- ^ TEAM. (1999). UEFA Champions League: Season Review 1998/9. Lucerne: TEAM.

- ^ «1. Facts & Figures». UEFA Champions League Statistics Handbook 2020/21 (PDF). UEFA.com. Union of European Football Associations. Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 October 2015. Retrieved 29 October 2020.

- ^ «Liverpool get in Champions League». BBC Sport. BBC. 10 June 2005. Archived from the original on 13 October 2005. Retrieved 11 December 2007.

- ^ «EXCO approves new coefficient system». UEFA.com. Union of European Football Associations. 20 May 2008. Archived from the original on 21 May 2008. Retrieved 12 September 2010.

- ^ a b «Harry Redknapp and Spurs given bitter pill of Europa League by Chelsea». The Guardian. Guardian News and Media. 20 May 2012. Retrieved 24 November 2012.

- ^ «Added bonus for UEFA Europa League winners». UEFA.com. Union of European Football Associations. 24 May 2013.

- ^ «UEFA Access List 2015/18 with explanations» (PDF). Bert Kassies. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 October 2014.

- ^ Bond, David (13 November 2007). «Clubs force UEFA’s Michel Platini into climbdown». The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 13 November 2007. Retrieved 2 December 2007.

- ^ «Platini’s Euro Cup plan rejected». BBC Sport. BBC. 12 December 2007. Archived from the original on 13 December 2007. Retrieved 11 December 2007.

- ^ «Arsène Wenger says Champions League place is a ‘trophy’«. Guardian. Archived from the original on 17 May 2014. Retrieved 15 May 2014.

- ^ «Arsenal’s Trophy Cabinet». Talksport. Archived from the original on 18 November 2013. Retrieved 15 May 2014.

- ^ a b «Champions League explained». PremierLeague.com. Retrieved 16 January 2020.

- ^ «Regulations of the UEFA Champions League 2011/12» (PDF). UEFA.com. p. 10. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 June 2011.

- ^ «Bayern Munich beat Paris Saint-Germain to win Champions League». ESPN. 23 August 2020. Retrieved 23 August 2020.

- ^ a b «Champions League and Europa League changes next season». UEFA.com (Press release). Union of European Football Associations. 27 February 2018. Retrieved 27 February 2018.

- ^ «UEFA club competition access list 2021–24» (PDF). UEFA.com. Union of European Football Associations. Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 December 2020.

- ^ a b c «How UEFA honours multiple European Cup winners». UEFA.com. Union of European Football Associations. Archived from the original on 31 July 2017. Retrieved 25 December 2019.

- ^ «Article 2.01 – Cup». Regulations of the UEFA Champions League (PDF). UEFA. p. 4. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 April 2003.

- ^ «2012/13 Season». Regulations of the UEFA Champions League: 2012–15 Cycle (PDF). Union of European Football Associations. p. 8. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 July 2012. Retrieved 22 September 2012.

- ^ «Distribution to clubs from the 2021/22 UEFA Champions League, UEFA Europa League and UEFA Europa Conference League and the 2021 UEFA Super Cup Payments for the qualifying phases Solidarity payments for non-participating clubs» (PDF) (Press release). UEFA. 20 May 2021. Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 May 2021. Retrieved 20 June 2021.

- ^ «Clubs benefit from Champions League revenue» (PDF). UEFAdirect. Union of European Football Associations (1): 1. October 2015. Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 November 2015. Retrieved 16 October 2015.

- ^ Thompson, Craig; Magnus, Ems (February 2003). «The Uefa Champions League Marketing» (PDF). Fiba Assist Magazine: 49–50. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 May 2008. Retrieved 19 May 2008.

- ^ «Regulations of the UEFA Champions League 2015–18 Cycle – 2015/2016 Season – Article 66 – Other Requirements» (PDF). UEFA. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 May 2015. Retrieved 30 June 2015.

- ^ «OPPO becomes UEFA Champions League global sponsor» (Press release). Nyon: UEFA. 18 July 2022.

- ^ Williams, Matthew. «FedEx delivers upgrade from Europa League to Champions League sponsor». SportBusiness. SBG Companies Limited. Retrieved 5 May 2021.

- ^ Ergocun, Gökhan (5 September 2022). «Turkish Airlines to sponsor UEFA Champions League». Ankara. Anadolu Agency.

- ^ «HEINEKEN extends UEFA club competition sponsorship» (Press release). UEFA. Retrieved 12 February 2018.

- ^ Carp, Sam. «Uefa’s Just Eat sponsorship covers Champions League and Women’s Euro». SportsPro. SportsPro Media Limited. Retrieved 23 March 2021.

- ^ Carp, Sam. «Uefa cashes in Mastercard renewal». SportsPro. SportsPro Media Limited. Archived from the original on 16 February 2018. Retrieved 12 February 2018.

- ^ «PepsiCo renews UEFA Champions League Partnership» (Press release). UEFA. Archived from the original on 12 February 2018. Retrieved 12 February 2018.

- ^ Lepitak, Stephen (11 February 2022). «Rockstar Energy Is PepsiCo’s Latest Brand to Sponsor the UEFA Champions League». Adweek.

- ^ «UEFA Champions League and PlayStation® Renew Partnership until 2024» (Press release). UEFA. 30 July 2021. Retrieved 15 September 2021.

- ^ «Socios.com becomes the Official Fan Token Partner of UEFA Club Competitions» (Press release). UEFA. 15 February 2022. Retrieved 27 February 2022.

- ^ «adidas extends European club football partnership» (Press release). UEFA. 15 December 2011. Archived from the original on 29 December 2014. Retrieved 30 June 2015.

- ^ «Hublot to partner Champions League and Europa League» (Press release). UEFA.

- ^ «UEFA Documents». UEFA. Archived from the original on 31 July 2021. Retrieved 31 July 2021.

- ^ UEFA Kit Regulations Edition 2012 (PDF). Nyon: UEFA. pp. 37, 38. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 April 2012. Retrieved 29 January 2014.

- ^ Devlin, John (3 July 2009). «An alternative to alcohol». truecoloursfootballkits.com. True Colours. Archived from the original on 12 September 2009. Retrieved 5 June 2013.

Rangers have actually sported the Center Parcs logo during the course of two seasons.

- ^ «Champions League final tops Super Bowl for TV market». BBC Sport. British Broadcasting Corporation. 31 January 2010. Archived from the original on 3 February 2010. Retrieved 25 February 2010.

- ^ Chishti, Faisal (30 May 2013). «Champions League final at Wembley drew TV audience of 360 million». Sportskeeda. Absolute Sports. Archived from the original on 30 December 2013. Retrieved 31 December 2013.

- ^ «Who has played 100 Champions League games?». UEFA.com. 11 December 2018. Archived from the original on 9 August 2020. Retrieved 9 August 2020.

- ^ «Champions League – All-time appearances». WorldFootball.net. Retrieved 19 October 2021.

- ^ «UEFA Champions League Statistics Handbook 2022/23» (PDF). UEFA.com. Union of European Football Associations (UEFA). p. 4. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 August 2020. Retrieved 9 August 2020.

- ^ «Champions League all-time top scorers». UEFA.com. 8 August 2020. Archived from the original on 10 August 2020. Retrieved 10 August 2020.

- ^ «Champions League + European Cup – All-time Topscorers». WorldFootball.net. Archived from the original on 10 August 2020. Retrieved 10 August 2020.

- ^ For players active prior to the introduction of the Champions League in 1992, see «All-time records 1955–2020» (PDF). UEFA. p. 8. Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 August 2020. Retrieved 10 August 2020.

- For all other players, see: «UEFA Champions League Statistics Handbook 2019/20» (PDF). UEFA. p. 8. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 August 2020. Retrieved 9 August 2020.

External links

- Official website

(in English, French, German, Italian, Spanish, Portuguese, and Russian)

|

|

| Organising body | UEFA |

|---|---|

| Founded | 1955; 68 years ago (rebranded in 1992) |

| Region | Europe |

| Number of teams |

|

| Qualifier for |

|

| Related competitions |

|

| Current champions | |

| Most successful club(s) | |

| Television broadcasters | List of broadcasters |

| Website | uefa.com/uefachampionsleague |

The UEFA Champions League (abbreviated as UCL, or sometimes, UEFA CL) is an annual club football competition organised by the Union of European Football Associations (UEFA) and contested by top-division European clubs, deciding the competition winners through a round robin group stage to qualify for a double-legged knockout format, and a single leg final. It is one of the most prestigious football tournaments in the world and the most prestigious club competition in European football, played by the national league champions (and, for some nations, one or more runners-up) of their national associations.

Introduced in 1955 as the Coupe des Clubs Champions Européens (French for European Champion Clubs’ Cup), and commonly known as the European Cup, it was initially a straight knockout tournament open only to the champions of Europe’s domestic leagues, with its winner reckoned as the European club champion. The competition took on its current name in 1992, adding a round-robin group stage in 1991 and allowing multiple entrants from certain countries since the 1997–98 season.[1] It has since been expanded, and while most of Europe’s national leagues can still only enter their champion, the strongest leagues now provide up to four teams.[2][3] Clubs that finish next-in-line in their national league, having not qualified for the Champions League, are eligible for the second-tier UEFA Europa League competition, and since 2021, for the third-tier UEFA Europa Conference League.[4]

In its present format, the Champions League begins in late June with a preliminary round, three qualifying rounds and a play-off round, all played over two legs. The six surviving teams enter the group stage, joining 26 teams qualified in advance. The 32 teams are drawn into eight groups of four teams and play each other in a double round-robin system. The eight group winners and eight runners-up proceed to the knockout phase that culminates with the final match in late May or early June.[5] The winner of the Champions League qualifies for the following year’s Champions League, the UEFA Super Cup, and the FIFA Club World Cup.[6][7]

Spanish clubs have the highest number of victories (19 wins), followed by England (14 wins) and Italy (12 wins). England has the largest number of winning teams, with five clubs having won the title. The competition has been won by 22 clubs, 13 of which have won it more than once, and eight successfully defended their title.[8] Real Madrid is the most successful club in the tournament’s history, having won it 14 times, including the first five seasons and also five of the last nine.[9] Only one club has won all of their matches in a single tournament en route to the tournament victory: Bayern Munich in the 2019–20 season.[10] Real Madrid are the current European champions, having beaten Liverpool 1–0 in the 2022 final.

History

| European Cup | |

|---|---|

| Season | Winners |

| 1955–56 | |

| 1956–57 | |

| 1957–58 | |

| 1958–59 | |

| 1959–60 | |

| 1960–61 | |

| 1961–62 | |

| 1962–63 | |

| 1963–64 | |

| 1964–65 | |

| 1965–66 | |

| 1966–67 | |

| 1967–68 | |

| 1968–69 | |

| 1969–70 | |

| 1970–71 | |

| 1971–72 | |

| 1972–73 | |

| 1973–74 | |

| 1974–75 | |

| 1975–76 | |

| 1976–77 | |

| 1977–78 | |

| 1978–79 | |

| 1979–80 | |

| 1980–81 | |

| 1981–82 | |

| 1982–83 | |

| 1983–84 | |

| 1984–85 | |

| 1985–86 | |

| 1986–87 | |

| 1987–88 | |

| 1988–89 | |

| 1989–90 | |

| 1990–91 | |

| 1991–92 | |

| UEFA Champions League | |

| 1992–93 | |

| 1993–94 | |

| 1994–95 | |

| 1995–96 | |

| 1996–97 | |

| 1997–98 | |

| 1998–99 | |

| 1999–2000 | |

| 2000–01 | |

| 2001–02 | |

| 2002–03 | |

| 2003–04 | |

| 2004–05 | |

| 2005–06 | |

| 2006–07 | |

| 2007–08 | |

| 2008–09 | |

| 2009–10 | |

| 2010–11 | |

| 2011–12 | |

| 2012–13 | |

| 2013–14 | |

| 2014–15 | |

| 2015–16 | |

| 2016–17 | |

| 2017–18 | |

| 2018–19 | |

| 2019–20 | |

| 2020–21 | |

| 2021–22 | |

| 2022–23 |

The first time the champions of two European leagues met was in what was nicknamed the 1895 World Championship, when English champions Sunderland beat Scottish champions Hearts 5–3.[11] The first pan-European tournament was the Challenge Cup, a competition between clubs in the Austro-Hungarian Empire.[12] Three years later, in 1900, the champions of Belgium, Netherlands and Switzerland, which were the only existing leagues in continental Europe at the time, participated in the Coupe Van der Straeten Ponthoz, thus being dubbed as the «club championship of the continent» by the local newspapers.[13][14]

The Mitropa Cup, a competition modelled after the Challenge Cup, was created in 1927, an idea of Austrian Hugo Meisl, and played between Central European clubs.[15] In 1930, the Coupe des Nations (French: Nations Cup), the first attempt to create a cup for national champion clubs of Europe, was played and organised by Swiss club Servette.[16] Held in Geneva, it brought together ten champions from across the continent. The tournament was won by Újpest of Hungary.[16] Latin European nations came together to form the Latin Cup in 1949.[17]

After receiving reports from his journalists over the highly successful South American Championship of Champions of 1948, Gabriel Hanot, editor of L’Équipe, began proposing the creation of a continent-wide tournament.[18] In interviews, Jacques Ferran (one of the founders of the European Champions Cup, together with Gabriel Hanot),[19] said that the South American Championship of Champions was the inspiration for the European Champions Cup.[20] After Stan Cullis declared Wolverhampton Wanderers «Champions of the World» following a successful run of friendlies in the 1950s, in particular a 3–2 friendly victory against Budapest Honvéd, Hanot finally managed to convince UEFA to put into practice such a tournament.[1] It was conceived in Paris in 1955 as the European Champion Clubs’ Cup.[1]

1955–1967: Beginnings

Alfredo Di Stéfano (pictured in 1959) led Real Madrid to five consecutive European Cup titles between 1956 and 1960.

The first European Cup took place during the 1955–56 season.[21][22] Sixteen teams participated (some by invitation): AC Milan (Italy), AGF Aarhus (Denmark), Anderlecht (Belgium), Djurgården (Sweden), Gwardia Warszawa (Poland), Hibernian (Scotland), Partizan (Yugoslavia), PSV Eindhoven (Netherlands), Rapid Wien (Austria), Real Madrid (Spain), Rot-Weiss Essen (West Germany), Saarbrücken (Saar), Servette (Switzerland), Sporting CP (Portugal), Stade de Reims (France), and Vörös Lobogó (Hungary).[21][22]

The first European Cup match took place on 4 September 1955, and ended in a 3–3 draw between Sporting CP and Partizan.[21][22] The first goal in European Cup history was scored by João Baptista Martins of Sporting CP.[21][22] The inaugural final took place at the Parc des Princes between Stade de Reims and Real Madrid on 13 June 1956.[21][22][23] The Spanish squad came back from behind to win 4–3 thanks to goals from Alfredo Di Stéfano and Marquitos, as well as two goals from Héctor Rial.[21][22][23] Real Madrid successfully defended the trophy next season in their home stadium, the Santiago Bernabéu, against Fiorentina.[24][25] After a scoreless first half, Real Madrid scored twice in six minutes to defeat the Italians.[23][24][25] In 1958, Milan failed to capitalise after going ahead on the scoreline twice, only for Real Madrid to equalise.[26][27] The final, held in Heysel Stadium, went to extra time where Francisco Gento scored the game-winning goal to allow Real Madrid to retain the title for the third consecutive season.[23][26][27]

In a rematch of the first final, Real Madrid faced Stade Reims at the Neckarstadion for the 1959 final, and won 2–0.[23][28][29] West German side Eintracht Frankfurt became the first non-Latin team to reach the European Cup final.[30][31] The 1960 final holds the record for the most goals scored, with Real Madrid beating Eintracht Frankfurt 7–3 in Hampden Park, courtesy of four goals by Ferenc Puskás and a hat-trick by Alfredo Di Stéfano.[23][30][31] This was Real Madrid’s fifth consecutive title, a record that still stands today.[8]

Real Madrid’s reign ended in the 1960–61 season when bitter rivals Barcelona dethroned them in the first round.[32][33] Barcelona were defeated in the final by Portuguese side Benfica 3–2 at Wankdorf Stadium.[32][33][34] Reinforced by Eusébio, Benfica defeated Real Madrid 5–3 at the Olympic Stadium in Amsterdam and kept the title for a second consecutive season.[34][35][36] Benfica wanted to repeat Real Madrid’s successful run of the 1950s after reaching the showpiece event of the 1962–63 European Cup, but a brace from Brazilian-Italian José Altafini at the Wembley Stadium gave the spoils to Milan, making the trophy leave the Iberian Peninsula for the first time ever.[37][38][39]

Inter Milan beat an ageing Real Madrid 3–1 in the Ernst-Happel-Stadion to win the 1963–64 season and replicate their local-rival’s success.[40][41][42] The title stayed in Milan for the third year in a row after Inter beat Benfica 1–0 at their home ground, the San Siro.[43][44][45] Under the leadership of Jock Stein, Scottish club Celtic beat Inter Milan 2–1 in the 1967 final to become the first British club to win the European Cup.[46][47] The Celtic players that day, all of whom were born within 30 miles (48 km) of Glasgow, subsequently became known as the «Lisbon Lions».[48]

1968–1978

Johan Cruyff (pictured in 1972) won the European Cup three times in a row with Ajax.

The 1967–68 season saw Manchester United become the first English team to win the European Cup, beating two-times winners Benfica 4–1 in the final.[49] This final came 10 years after the Munich air disaster, which had claimed the lives of eight United players and left their manager, Matt Busby, fighting for his life.[50] In the 1968–69 season, Ajax became the first Dutch team to reach the European Cup final, but they were beaten 4–1 by Milan, who claimed their second European Cup, with Pierino Prati scoring a hat-trick.[51]

The 1969–70 season saw the first Dutch winners of the competition. Feyenoord knocked out the defending champions, Milan in the second round,[52] before beating Celtic in the final.[53] In the 1970–71 season Ajax won the title, beating Greek side Panathinaikos in the final.[54] the season saw a number of changes, with penalty shoot-outs being introduced, and the away goals rule being changed so that it would be used in all rounds except the final.[55] It was also the first time a Greek team reached the final, as well as the first season that Real Madrid failed to qualify, having finished sixth in La Liga the previous season.[56] Ajax went on to win the competition three years in row (1971 to 1973), which Bayern Munich emulated from 1974 to 1976, before Liverpool won their first two titles in 1977 and 1978.[57]

Anthem

«Magic…it’s magic above all else. When you hear the anthem it captivates you straight away.»

—Zinedine Zidane[58]

The UEFA Champions League anthem, officially titled simply as «Champions League», was written by Tony Britten, and is an adaptation of George Frideric Handel’s 1727 anthem Zadok the Priest (one of his Coronation Anthems).[59][60] UEFA commissioned Britten in 1992 to arrange an anthem, and the piece was performed by London’s Royal Philharmonic Orchestra and sung by the Academy of St. Martin in the Fields.[59] Stating that «the anthem is now almost as iconic as the trophy», UEFA’s official website adds it is «known to set the hearts of many of the world’s top footballers aflutter».[59]

The two teams line up for the UEFA Champions League Anthem before each match and a flag of the Champions League «starball» logo is waved in the centre circle.

The chorus contains the three official languages used by UEFA: English, German, and French.[61] The climactic moment is set to the exclamations ‘Die Meister! Die Besten! Les Grandes Équipes! The Champions!’.[62] The anthem’s chorus is played before each UEFA Champions League game as the two teams are lined up, as well as at the beginning and end of television broadcasts of the matches. In addition to the anthem, there is also entrance music, which contains parts of the anthem itself, which is played as teams enter the field.[63] The complete anthem is about three minutes long, and has two short verses and the chorus.[61]

Special vocal versions have been performed live at the Champions League final with lyrics in other languages, changing over to the host nation’s language for the chorus. These versions were performed by Andrea Bocelli (Italian) (Rome 2009, Milan 2016 and Cardiff 2017), Juan Diego Flores (Spanish) (Madrid 2010), All Angels (Wembley 2011), Jonas Kaufmann and David Garrett (Munich 2012), and Mariza (Lisbon 2014). In the 2013 final at Wembley Stadium, the chorus was played twice. In the 2018 and 2019 finals, held in Kyiv and Madrid respectively, the instrumental version of the chorus was played, by 2Cellos (2018) and Asturia Girls (2019).[64][65] The anthem has been released commercially in its original version on iTunes and Spotify with the title of Champions League Theme. In 2018, composer Hans Zimmer remixed the anthem with rapper Vince Staples for EA Sports’ video game FIFA 19, with it also featuring in the game’s reveal trailer.[66]

Branding

The «starball» logo is incorporated into the design of the competition’s official match ball, the Adidas Finale.

In 1991, UEFA asked its commercial partner, Television Event and Media Marketing (TEAM), to help brand the Champions League. This resulted in the anthem, «house colours» of black and white or silver and a logo, and the «starball». The starball was created by Design Bridge, a London-based firm selected by TEAM after a competition.[67] TEAM gives particular attention to detail in how the colours and starball are depicted at matches. According to TEAM, «Irrespective of whether you are a spectator in Moscow or Milan, you will always see the same stadium dressing materials, the same opening ceremony featuring the ‘starball’ centre circle ceremony, and hear the same UEFA Champions League Anthem». Based on research it conducted, TEAM concluded that by 1999, «the starball logo had achieved a recognition rate of 94 percent among fans».[68]

Format

Qualification

A map of UEFA countries whose teams have reached the group stage of the UEFA Champions League

UEFA member state that has been represented in the group stage

UEFA member state that has not been represented in the group stage

The UEFA Champions League begins with a double round-robin group stage of 32 teams, which since the 2009–10 season is preceded by two qualification ‘streams’ for teams that do not receive direct entry to the tournament proper. The two streams are divided between teams qualified by virtue of being league champions, and those qualified by virtue of finishing second or third in their national championship.

The number of teams that each association enters into the UEFA Champions League is based upon the UEFA coefficients of the member associations. These coefficients are generated by the results of clubs representing each association during the previous five Champions League and UEFA Cup/Europa League seasons. The higher an association’s coefficient, the more teams represent the association in the Champions League, and the fewer qualification rounds the association’s teams must compete in.

Four of the remaining six qualifying places are granted to the winners of a six-round qualifying tournament between the remaining 43 or 44 national champions, within which those champions from associations with higher coefficients receive byes to later rounds. The other two are granted to the winners of a three-round qualifying tournament between 10–11 clubs from the associations ranked 5–6 through 15, which have qualified based upon finishing second or third in their respective national league.

In addition to sporting criteria, any club must be licensed by its national association to participate in the Champions League. To obtain a license, the club must meet certain stadium, infrastructure and finance requirements.

In 2005–06, Liverpool and Artmedia Bratislava became the first teams to reach the Champions League group stage after playing in all three qualifying rounds. Real Madrid and Barcelona hold the record for the most appearances in the group stage, having qualified 25 times, followed by FC Porto and Bayern Munich on 24.[69]

Between 1999 and 2008, no differentiation was made between champions and non-champions in qualification. The 16 top-ranked teams spread across the biggest domestic leagues qualified directly for the tournament group stage. Prior to this, three preliminary knockout qualifying rounds whittled down the remaining teams, with teams starting in different rounds.

An exception to the usual European qualification system happened in 2005, after Liverpool won the Champions League the year before, but did not finish in a Champions League qualification place in the Premier League that season. UEFA gave special dispensation for Liverpool to enter the Champions League, giving England five qualifiers.[70] UEFA subsequently ruled that the defending champions qualify for the competition the following year regardless of their domestic league placing. However, for those leagues with four entrants in the Champions League, this meant that, if the Champions League winner fell outside of its domestic league’s top four, it would qualify at the expense of the fourth-placed team in the league. Until 2015–16, no association could have more than four entrants in the Champions League.[71] In May 2012, Tottenham Hotspur finished fourth in the 2011–12 Premier League, two places ahead of Chelsea, but failed to qualify for the 2012–13 Champions League, after Chelsea won the 2012 final.[72] Tottenham were demoted to the 2012–13 UEFA Europa League.[72]

In May 2013,[73] it was decided that, starting from the 2015–16 season (and continuing at least for the three-year cycle until the 2017–18 season), the winners of the previous season’s UEFA Europa League would qualify for the UEFA Champions League, entering at least the play-off round, and entering the group stage if the berth reserved for the Champions League title holders was not used. The previous limit of a maximum of four teams per association was increased to five, meaning that a fourth-placed team from one of the top three ranked associations would only have to be moved to the Europa League if both the Champions League and Europa League winners came from that association and both finished outside the top four of their domestic league.[74]

In 2007, Michel Platini, the UEFA president, had proposed taking one place from the three leagues with four entrants and allocating it to that nation’s cup winners. This proposal was rejected in a vote at a UEFA Strategy Council meeting.[75] In the same meeting, however, it was agreed that the third-placed team in the top three leagues would receive automatic qualification for the group stage, rather than entry into the third qualifying round, while the fourth-placed team would enter the play-off round for non-champions, guaranteeing an opponent from one of the top 15 leagues in Europe. This was part of Platini’s plan to increase the number of teams qualifying directly into the group stage, while simultaneously increasing the number of teams from lower-ranked nations in the group stage.[76]

In 2012, Arsène Wenger referred to qualifying for the Champions League by finishing in the top four places in the English Premier League as the «4th Place Trophy». The phrase was coined after a pre-match conference when he was questioned about Arsenal’s lack of a trophy after exiting the FA Cup. He said «The first trophy is to finish in the top four».[77] At Arsenal’s 2012 AGM, Wenger was also quoted as saying: «For me there are five trophies every season: Premier League, Champions League, the third is to qualify for the Champions League…»[78]

Group stage and knockout phase

The tournament proper begins with a group stage of 32 teams, divided into eight groups of four.[79] The draw to determine which teams go into each group is seeded based on teams’ performance in UEFA competitions, and no group may contain more than one club from each nation. Each team plays six group stage games, meeting the other three teams in its group home and away in a round-robin format.[79] The winning team and the runners-up from each group then progress to the next round. The third-placed team enters the UEFA Europa League.