|

|

This article is missing information about critical and academic analysis, as well as contemporary reactions and its influence (on other political theorists, on governments, perhaps even enlightened absolutism). Please expand the article to include this information. Further details may exist on the talk page. (January 2022) |

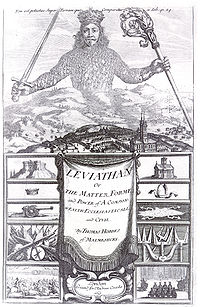

Frontispiece of Leviathan by Abraham Bosse, with input from Hobbes |

|

| Author | Thomas Hobbes |

|---|---|

| Country | England |

| Language | English, Latin (Hobbes produced a new version of Leviathan in Latin in 1668:[1] Leviathan, sive De materia, forma, & potestate civitatis ecclesiasticae et civilis.[2] Many passages in the Latin version differ from the English version.)[3] |

| Genre | Political philosophy |

|

Publication date |

April 1651[4] |

| ISBN | 978-1439297254 |

| Text | Leviathan at Wikisource |

Leviathan or The Matter, Forme and Power of a Commonwealth Ecclesiasticall and Civil, commonly referred to as Leviathan, is a book written by Thomas Hobbes (1588–1679) and published in 1651 (revised Latin edition 1668).[1][5][6] Its name derives from the biblical Leviathan. The work concerns the structure of society and legitimate government, and is regarded as one of the earliest and most influential examples of social contract theory.[7] Written during the English Civil War (1642–1651), it argues for a social contract and rule by an absolute sovereign. Hobbes wrote that civil war and the brute situation of a state of nature («the war of all against all») could be avoided only by strong, undivided government.

Content[edit]

Title[edit]

The title of Hobbes’s treatise alludes to the Leviathan mentioned in the Book of Job. In contrast to the simply informative titles usually given to works of early modern political philosophy, such as John Locke’s Two Treatises of Government or Hobbes’s own earlier work The Elements of Law, Hobbes selected a more poetic name for this more provocative treatise.

Frontispiece[edit]

After lengthy discussion with Thomas Hobbes, the Parisian Abraham Bosse created the etching for the book’s famous frontispiece in the géometrique style which Bosse himself had refined. It is similar in organisation to the frontispiece of Hobbes’ De Cive (1642), created by Jean Matheus. The frontispiece has two main elements, of which the upper part is by far the more striking.

In it, a giant crowned figure is seen emerging from the landscape, clutching a sword and a crosier, beneath a quote from the Book of Job—»Non est potestas Super Terram quae Comparetur ei. Iob. 41 . 24» («There is no power on earth to be compared to him. Job 41 . 24»)—further linking the figure to the monster of the book. (Due to disagreements over the precise location of the chapters and verses when they were divided in the Late Middle Ages, the verse Hobbes quotes is usually given as Job 41:33 in modern Christian translations into English,[8] Job 41:25 in the Masoretic text, Septuagint, and the Luther Bible; it is Job 41:24 in the Vulgate.) The torso and arms of the figure are composed of over three hundred persons, in the style of Giuseppe Arcimboldo; all are facing away from the viewer, with just the giant’s head having visible facial features. (A manuscript of Leviathan created for Charles II in 1651 has notable differences – a different main head but significantly the body is also composed of many faces, all looking outwards from the body and with a range of expressions.)

The lower portion is a triptych, framed in a wooden border. The centre form contains the title on an ornate curtain. The two sides reflect the sword and crosier of the main figure – earthly power on the left and the powers of the church on the right. Each side element reflects the equivalent power – castle to church, crown to mitre, cannon to excommunication, weapons to logic, and the battlefield to the religious courts. The giant holds the symbols of both sides, reflecting the union of secular, and spiritual in the sovereign, but the construction of the torso also makes the figure the state.

Part I: Of Man[edit]

Hobbes begins his treatise on politics with an account of human nature. He presents an image of man as matter in motion, attempting to show through example how everything about humanity can be explained materialistically, that is, without recourse to an incorporeal, immaterial soul or a faculty for understanding ideas that are external to the human mind.

Life is but a motion of limbs. For what is the heart, but a spring; and the nerves, but so many strings; and the joints, but so many wheels, giving motion to the whole body, such as was intended by the Artificer?[9]

Hobbes proceeds by defining terms clearly and unsentimentally. Good and evil are nothing more than terms used to denote an individual’s appetites and desires, while these appetites and desires are nothing more than the tendency to move toward or away from an object. Hope is nothing more than an appetite for a thing combined with an opinion that it can be had. He suggests that the dominant political theology of the time, Scholasticism, thrives on confused definitions of everyday words, such as incorporeal substance, which for Hobbes is a contradiction in terms.

Hobbes describes human psychology without any reference to the summum bonum, or greatest good, as previous thought had done. According to Hobbes, not only is the concept of a summum bonum superfluous, but given the variability of human desires, there could be no such thing. Consequently, any political community that sought to provide the greatest good to its members would find itself driven by competing conceptions of that good with no way to decide among them. The result would be civil war.

However, Hobbes states that there is a summum malum, or greatest evil. This is the fear of violent death. A political community can be oriented around this fear.

Since there is no summum bonum, the natural state of man is not to be found in a political community that pursues the greatest good. But to be outside of a political community is to be in an anarchic condition. Given human nature, the variability of human desires, and need for scarce resources to fulfill those desires, the state of nature, as Hobbes calls this anarchic condition, must be a war of all against all. Even when two men are not fighting, there is no guarantee that the other will not try to kill him for his property or just out of an aggrieved sense of honour, and so they must constantly be on guard against one another. It is even reasonable to preemptively attack one’s neighbour.

In such condition there is no place for industry, because the fruit thereof is uncertain, and consequently no culture of the earth, no navigation nor the use of commodities that may be imported by sea, no commodious building, no instruments of moving and removing such things as require much force, no knowledge of the face of the earth, no account of time, no arts, no letters, no society, and which is worst of all, continual fear and danger of violent death, and the life of man, solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short.[10]

The desire to avoid the state of nature, as the place where the summum malum of violent death is most likely to occur, forms the polestar of political reasoning. It suggests a number of laws of nature, although Hobbes is quick to point out that they cannot properly speaking be called «laws», since there is no one to enforce them. The first thing that reason suggests is to seek peace, but that where peace cannot be had, to use all of the advantages of war.[11] Hobbes is explicit that in the state of nature nothing can be considered just or unjust, and every man must be considered to have a right to all things.[12] The second law of nature is that one ought to be willing to renounce one’s right to all things where others are willing to do the same, to quit the state of nature, and to erect a commonwealth with the authority to command them in all things. Hobbes concludes Part One by articulating an additional seventeen laws of nature that make the performance of the first two possible and by explaining what it would mean for a sovereign to represent the people even when they disagree with the sovereign.

Part II: Of Commonwealth[edit]

The purpose of a commonwealth is given at the start of Part II:

THE final cause, end, or design of men (who naturally love liberty, and dominion over others) in the introduction of that restraint upon themselves, in which we see them live in Commonwealths, is the foresight of their own preservation, and of a more contented life thereby; that is to say, of getting themselves out from that miserable condition of war which is necessarily consequent, as hath been shown, to the natural passions of men when there is no visible power to keep them in awe, and tie them by fear of punishment to the performance of their covenants…

The commonwealth is instituted when all agree in the following manner: I authorise and give up my right of governing myself to this man, or to this assembly of men, on this condition; that thou give up, thy right to him, and authorise all his actions in like manner.

The sovereign has twelve principal rights:[13]

- Because a successive covenant cannot override a prior one, the subjects cannot (lawfully) change the form of government.

- Because the covenant forming the commonwealth results from subjects giving to the sovereign the right to act for them, the sovereign cannot possibly breach the covenant; and therefore the subjects can never argue to be freed from the covenant because of the actions of the sovereign.

- The sovereign exists because the majority has consented to his rule; the minority have agreed to abide by this arrangement and must then assent to the sovereign’s actions.

- Every subject is author of the acts of the sovereign: hence the sovereign cannot injure any of his subjects and cannot be accused of injustice.

- Following this, the sovereign cannot justly be put to death by the subjects.

- The purpose of the commonwealth is peace, and the sovereign has the right to do whatever he thinks necessary for the preserving of peace and security and prevention of discord. Therefore, the sovereign may judge what opinions and doctrines are averse, who shall be allowed to speak to multitudes, and who shall examine the doctrines of all books before they are published.

- To prescribe the rules of civil law and property.

- To be judge in all cases.

- To make war and peace as he sees fit and to command the army.

- To choose counsellors, ministers, magistrates and officers.

- To reward with riches and honour or to punish with corporal or pecuniary punishment or ignominy.

- To establish laws about honour and a scale of worth.

Hobbes explicitly rejects the idea of Separation of Powers. In item 6 Hobbes is explicitly in favour of censorship of the press and restrictions on the rights of free speech should they be considered desirable by the sovereign to promote order.

Types[edit]

There are three (monarchy, aristocracy and democracy):

The difference of Commonwealths consisted in the difference of the sovereign, or the person representative of all and every one of the multitude. And because the sovereignty is either in one man, or in an assembly of more than one; and into that assembly either every man hath right to enter, or not every one, but certain men distinguished from the rest; it is manifest there can be but three kinds of Commonwealth. For the representative must needs be one man, or more; and if more, then it is the assembly of all, or but of a part. When the representative is one man, then is the Commonwealth a monarchy; when an assembly of all that will come together, then it is a democracy, or popular Commonwealth; when an assembly of a part only, then it is called an aristocracy.

And only three; since unlike Aristotle he does not sub-divide them into «good» and «deviant»:

Other kind of Commonwealth there can be none: for either one, or more, or all, must have the sovereign power (which I have shown to be indivisible) entire. There be other names of government in the histories and books of policy; as tyranny and oligarchy; but they are not the names of other forms of government, but of the same forms misliked. For they that are discontented under monarchy call it tyranny; and they that are displeased with aristocracy call it oligarchy: so also, they which find themselves grieved under a democracy call it anarchy, which signifies want of government; and yet I think no man believes that want of government is any new kind of government: nor by the same reason ought they to believe that the government is of one kind when they like it, and another when they mislike it or are oppressed by the governors.

And monarchy is the best, on practical grounds:

The difference between these three kinds of Commonwealth consisteth not in the difference of power, but in the difference of convenience or aptitude to produce the peace and security of the people; for which end they were instituted. And to compare monarchy with the other two, we may observe: first, that whosoever beareth the person of the people, or is one of that assembly that bears it, beareth also his own natural person. And though he be careful in his politic person to procure the common interest, yet he is more, or no less, careful to procure the private good of himself, his family, kindred and friends; and for the most part, if the public interest chance to cross the private, he prefers the private: for the passions of men are commonly more potent than their reason. From whence it follows that where the public and private interest are most closely united, there is the public most advanced. Now in monarchy the private interest is the same with the public. The riches, power, and honour of a monarch arise only from the riches, strength, and reputation of his subjects. For no king can be rich, nor glorious, nor secure, whose subjects are either poor, or contemptible, or too weak through want, or dissension, to maintain a war against their enemies; whereas in a democracy, or aristocracy, the public prosperity confers not so much to the private fortune of one that is corrupt, or ambitious, as doth many times a perfidious advice, a treacherous action, or a civil war.

Succession[edit]

The right of succession always lies with the sovereign. Democracies and aristocracies have easy succession; monarchy is harder:

The greatest difficulty about the right of succession is in monarchy: and the difficulty ariseth from this, that at first sight, it is not manifest who is to appoint the successor; nor many times who it is whom he hath appointed. For in both these cases, there is required a more exact ratiocination than every man is accustomed to use.

Because in general people haven’t thought carefully. However, the succession is definitely in the gift of the monarch:

As to the question who shall appoint the successor of a monarch that hath the sovereign authority… we are to consider that either he that is in possession has right to dispose of the succession, or else that right is again in the dissolved multitude. … Therefore it is manifest that by the institution of monarchy, the disposing of the successor is always left to the judgement and will of the present possessor.

But, it is not always obvious who the monarch has appointed:

And for the question which may arise sometimes, who it is that the monarch in possession hath designed to the succession and inheritance of his power

However, the answer is:

it is determined by his express words and testament; or by other tacit signs sufficient.

And this means:

By express words, or testament, when it is declared by him in his lifetime, viva voce, or by writing; as the first emperors of Rome declared who should be their heirs.

Note that (perhaps rather radically) this does not have to be any blood relative:

For the word heir does not of itself imply the children or nearest kindred of a man; but whomsoever a man shall any way declare he would have to succeed him in his estate. If therefore a monarch declare expressly that such a man shall be his heir, either by word or writing, then is that man immediately after the decease of his predecessor invested in the right of being monarch.

However, practically this means:

But where testament and express words are wanting, other natural signs of the will are to be followed: whereof the one is custom. And therefore where the custom is that the next of kindred absolutely succeedeth, there also the next of kindred hath right to the succession; for that, if the will of him that was in possession had been otherwise, he might easily have declared the same in his lifetime…

Religion[edit]

In Leviathan, Hobbes explicitly states that the sovereign has authority to assert power over matters of faith and doctrine and that if he does not do so, he invites discord. Hobbes presents his own religious theory but states that he would defer to the will of the sovereign (when that was re-established: again, Leviathan was written during the Civil War) as to whether his theory was acceptable. Hobbes’ materialistic presuppositions also led him to hold a view which was considered highly controversial at the time. Hobbes rejected the idea of incorporeal substances and subsequently argued that even God himself was a corporeal substance. Although Hobbes never explicitly stated he was an atheist, many allude to the possibility that he was.

Taxation[edit]

Hobbes also touched upon the sovereign’s ability to tax in Leviathan, although he is not as widely cited for his economic theories as he is for his political theories.[14] Hobbes believed that equal justice includes the equal imposition of taxes. The equality of taxes doesn’t depend on equality of wealth, but on the equality of the debt that every man owes to the commonwealth for his defence and the maintenance of the rule of law.[15] Hobbes also championed public support for those unable to maintain themselves by labour, which would presumably be funded by taxation. He advocated public encouragement of works of Navigation etc. to usefully employ the poor who could work.

Part III: Of a Christian Commonwealth[edit]

In Part III Hobbes seeks to investigate the nature of a Christian commonwealth. This immediately raises the question of which scriptures we should trust, and why. If any person may claim supernatural revelation superior to the civil law, then there would be chaos, and Hobbes’ fervent desire is to avoid this. Hobbes thus begins by establishing that we cannot infallibly know another’s personal word to be divine revelation:

When God speaketh to man, it must be either immediately or by mediation of another man, to whom He had formerly spoken by Himself immediately. How God speaketh to a man immediately may be understood by those well enough to whom He hath so spoken; but how the same should be understood by another is hard, if not impossible, to know. For if a man pretend to me that God hath spoken to him supernaturally, and immediately, and I make doubt of it, I cannot easily perceive what argument he can produce to oblige me to believe it.

This is good, but if applied too fervently would lead to all the Bible being rejected. So, Hobbes says, we need a test: and the true test is established by examining the books of scripture, and is:

So that it is manifest that the teaching of the religion which God hath established, and the showing of a present miracle, joined together, were the only marks whereby the Scripture would have a true prophet, that is to say, immediate revelation, to be acknowledged; of them being singly sufficient to oblige any other man to regard what he saith.

Seeing therefore miracles now cease, we have no sign left whereby to acknowledge the pretended revelations or inspirations of any private man; nor obligation to give ear to any doctrine, farther than it is conformable to the Holy Scriptures, which since the time of our Saviour supply the place and sufficiently recompense the want of all other prophecy

«Seeing therefore miracles now cease» means that only the books of the Bible can be trusted. Hobbes then discusses the various books which are accepted by various sects, and the «question much disputed between the diverse sects of Christian religion, from whence the Scriptures derive their authority». To Hobbes, «it is manifest that none can know they are God’s word (though all true Christians believe it) but those to whom God Himself hath revealed it supernaturally». And therefore «The question truly stated is: by what authority they are made law?»

Unsurprisingly, Hobbes concludes that ultimately there is no way to determine this other than the civil power:

He therefore to whom God hath not supernaturally revealed that they are His, nor that those that published them were sent by Him, is not obliged to obey them by any authority but his whose commands have already the force of laws; that is to say, by any other authority than that of the Commonwealth, residing in the sovereign, who only has the legislative power.

He discusses the Ten Commandments, and asks «who it was that gave to these written tables the obligatory force of laws. There is no doubt but they were made laws by God Himself: but because a law obliges not, nor is law to any but to them that acknowledge it to be the act of the sovereign, how could the people of Israel, that were forbidden to approach the mountain to hear what God said to Moses, be obliged to obedience to all those laws which Moses propounded to them?» and concludes, as before, that «making of the Scripture law, belonged to the civil sovereign.»

Finally: «We are to consider now what office in the Church those persons have who, being civil sovereigns, have embraced also the Christian faith?» to which the answer is: «Christian kings are still the supreme pastors of their people, and have power to ordain what pastors they please, to teach the Church, that is, to teach the people committed to their charge.»

There is an enormous amount of biblical scholarship in this third part. However, once Hobbes’ initial argument is accepted (that no-one can know for sure anyone else’s divine revelation) his conclusion (the religious power is subordinate to the civil) follows from his logic. The very extensive discussions of the chapter were probably necessary for its time. The need (as Hobbes saw it) for the civil sovereign to be supreme arose partly from the many sects that arose around the civil war, and to quash the Pope of Rome’s challenge, to which Hobbes devotes an extensive section.

Part IV: Of the Kingdom of Darkness[edit]

Hobbes named Part IV of his book «Kingdom of Darkness». By this Hobbes does not mean Hell (he did not believe in Hell or Purgatory),[16] but the darkness of ignorance as opposed to the light of true knowledge. Hobbes’ interpretation is largely unorthodox and so sees much darkness in what he sees as the misinterpretation of Scripture.

- This considered, the kingdom of darkness… is nothing else but a confederacy of deceivers that, to obtain dominion over men in this present world, endeavour, by dark and erroneous doctrines, to extinguish in them the light…[17]

Hobbes enumerates four causes of this darkness.

The first is by extinguishing the light of scripture through misinterpretation. Hobbes sees the main abuse as teaching that the kingdom of God can be found in the church, thus undermining the authority of the civil sovereign. Another general abuse of scripture, in his view, is the turning of consecration into conjuration, or silly ritual.

The second cause is the demonology of the heathen poets: in Hobbes’s opinion, demons are nothing more than constructs of the brain. Hobbes then goes on to criticize what he sees as many of the practices of Catholicism: «Now for the worship of saints, and images, and relics, and other things at this day practiced in the Church of Rome, I say they are not allowed by the word of God».

The third is by mixing with the Scripture diverse relics of the religion, and much of the vain and erroneous philosophy of the Greeks, especially of Aristotle. Hobbes has little time for the various disputing sects of philosophers and objects to what people have taken «From Aristotle’s civil philosophy, they have learned to call all manner of Commonwealths but the popular (such as was at that time the state of Athens), tyranny». At the end of this comes an interesting section (darkness is suppressing true knowledge as well as introducing falsehoods), which would appear to bear on the discoveries of Galileo Galilei. «Our own navigations make manifest, and all men learned in human sciences now acknowledge, there are antipodes» (i.e., the Earth is round) «…Nevertheless, men… have been punished for it by authority ecclesiastical. But what reason is there for it? Is it because such opinions are contrary to true religion? That cannot be, if they be true.» However, Hobbes is quite happy for the truth to be suppressed if necessary: if «they tend to disorder in government, as countenancing rebellion or sedition? Then let them be silenced, and the teachers punished» – but only by the civil authority.

The fourth is by mingling with both these, false or uncertain traditions, and feigned or uncertain history.

Hobbes finishes by inquiring who benefits from the errors he diagnoses:

- Cicero maketh honourable mention of one of the Cassii, a severe judge amongst the Romans, for a custom he had in criminal causes, when the testimony of the witnesses was not sufficient, to ask the accusers, cui bono; that is to say, what profit, honour, or other contentment the accused obtained or expected by the fact. For amongst presumptions, there is none that so evidently declareth the author as doth the benefit of the action.

Hobbes concludes that the beneficiaries are the churches and churchmen.

See also[edit]

- Behemoth by Thomas Hobbes

- Classical republicanism

- John Locke

- Scientia potentia est

- Hobbes’s moral and political philosophy

References[edit]

- ^ a b Glen Newey, Routledge Philosophy GuideBook to Hobbes and Leviathan, Routledge, 2008, p. 18.

- ^ «Leviathan, sive, de materia, forma, & potestate civitatis ecclesiasticae et civilis». 1668.

- ^ Thomas Hobbes: Leviathan – Oxford University Press.

- ^ Thomas, Hobbes (2006). Thomas Hobbes : Leviathan. Rogers, G. A. J.,, Schuhmann, Karl (A critical ed.). London: Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 12. ISBN 9781441110985. OCLC 882503096.

- ^ Hilary Brown, Luise Gottsched the Translator, Camden House, 2012, p. 54.

- ^ It’s in this edition that Hobbes coined the expression auctoritas non veritas facit legem, which means «authority, not truth, makes law»: book 2, chapter 26, p. 133.

- ^ «Hobbes’s Moral and Political Philosophy». Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. 2018. (Retrieved 11 March 2009)

- ^ Job 41:33

- ^ Hobbes, Leviathan, Introduction.

- ^ Hobbes, Leviathan, XIII.9.

- ^ Hobbes, Leviathan, XIV.4.

- ^ Hobbes, Leviathan, XIII.13.

- ^ Hobbes, Leviathan, XVIII.

- ^ Aaron Levy (October 1954). «Economic Views of Thomas Hobbes». Journal of the History of Ideas. 15 (4): 589–595. doi:10.2307/2707677. JSTOR 2707677.

- ^ «Leviathan: Part II. Commonwealth; Chapters 17–31» (PDF). Early Modern Texts.

- ^ Chapter XLVI: Lastly, for the errors brought in from false or uncertain history, what is all the legend of fictitious miracles in the lives of the saints; and all the histories of apparitions and ghosts alleged by the doctors of the Roman Church, to make good their doctrines of hell and purgatory, the power of exorcism, and other doctrines which have no warrant, neither in reason nor Scripture; as also all those traditions which they call the unwritten word of God; but old wives’ fables?

- ^ «Chapter XLIV». Archived from the original on 3 August 2004. Retrieved 27 September 2004.

Further reading[edit]

Editions of Leviathan[edit]

- Leviathan. Revised Edition, eds. A.P. Martinich and Brian Battiste. Peterborough, ON: Broadview Press, 2010. ISBN 978-1-55481-003-1.[1] Archived 6 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- Leviathan: Or the Matter, Forme, and Power of a Commonwealth Ecclesiasticall and Civill, ed. by Ian Shapiro (Yale University Press; 2010).

- Leviathan, Critical edition by Noel Malcolm in three volumes: 1. Editorial Introduction; 2 and 3. The English and Latin Texts, Oxford University Press, 2012 (Clarendon Edition of the Works of Thomas Hobbes).

Critical studies[edit]

- Bagby, Laurie M. Hobbes’s Leviathan : Reader’s Guide, New York: Continuum, 2007.

- Baumrin, Bernard Herbert (ed.) Hobbes’s Leviathan – interpretation and criticism Belmont, CA: Wadsworth, 1969.

- Cranston, Maurice. «The Leviathan» History Today (Oct 1951) 1#10 pp. 17–21

- Harrison, Ross. Hobbes, Locke, and Confusion’s Masterpiece: an Examination of Seventeenth-Century Political Philosophy. Cambridge University Press, 2003.

- Hood, Francis Campbell. The divine politics of Thomas Hobbes – an interpretation of Leviathan, Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1964.

- Johnston, David. The rhetoric of Leviathan – Thomas Hobbes and the politics of cultural transformation, Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1986.

- Newey, Glen. Routledge Philosophy Guidebook to Hobbes and Leviathan, New York: Routledge, 2008.

- Rogers, Graham Alan John. Leviathan – contemporary responses to the political theory of Thomas Hobbes Bristol: Thoemmes Press, 1995.

- Schmitt, Carl. The Leviathan in the state theory of Thomas Hobbes – meaning and failure of a political symbol, Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2008 (earlier: Greenwood Press, 1996).

- Springborg, Patricia. The Cambridge Companion to Hobbes’s Leviathan, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007.

- Windolph, Francis Lyman. Leviathan and natural law, Princeton NJ: Princeton University Press, 1951.

- Zagorin, Perez. Hobbes and the Law of Nature, Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2009.

External links[edit]

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Leviathan.

Wikisource has original text related to this article:

- Reprint from the 1651 edition

- Leviathan at Project Gutenberg

Leviathan public domain audiobook at LibriVox

- Full text online at oregonstate.edu

- A reduced version of Leviathan at earlymoderntexts.com

- Scan of 1651 edition

|

|

This article is missing information about critical and academic analysis, as well as contemporary reactions and its influence (on other political theorists, on governments, perhaps even enlightened absolutism). Please expand the article to include this information. Further details may exist on the talk page. (January 2022) |

Frontispiece of Leviathan by Abraham Bosse, with input from Hobbes |

|

| Author | Thomas Hobbes |

|---|---|

| Country | England |

| Language | English, Latin (Hobbes produced a new version of Leviathan in Latin in 1668:[1] Leviathan, sive De materia, forma, & potestate civitatis ecclesiasticae et civilis.[2] Many passages in the Latin version differ from the English version.)[3] |

| Genre | Political philosophy |

|

Publication date |

April 1651[4] |

| ISBN | 978-1439297254 |

| Text | Leviathan at Wikisource |

Leviathan or The Matter, Forme and Power of a Commonwealth Ecclesiasticall and Civil, commonly referred to as Leviathan, is a book written by Thomas Hobbes (1588–1679) and published in 1651 (revised Latin edition 1668).[1][5][6] Its name derives from the biblical Leviathan. The work concerns the structure of society and legitimate government, and is regarded as one of the earliest and most influential examples of social contract theory.[7] Written during the English Civil War (1642–1651), it argues for a social contract and rule by an absolute sovereign. Hobbes wrote that civil war and the brute situation of a state of nature («the war of all against all») could be avoided only by strong, undivided government.

Content[edit]

Title[edit]

The title of Hobbes’s treatise alludes to the Leviathan mentioned in the Book of Job. In contrast to the simply informative titles usually given to works of early modern political philosophy, such as John Locke’s Two Treatises of Government or Hobbes’s own earlier work The Elements of Law, Hobbes selected a more poetic name for this more provocative treatise.

Frontispiece[edit]

After lengthy discussion with Thomas Hobbes, the Parisian Abraham Bosse created the etching for the book’s famous frontispiece in the géometrique style which Bosse himself had refined. It is similar in organisation to the frontispiece of Hobbes’ De Cive (1642), created by Jean Matheus. The frontispiece has two main elements, of which the upper part is by far the more striking.

In it, a giant crowned figure is seen emerging from the landscape, clutching a sword and a crosier, beneath a quote from the Book of Job—»Non est potestas Super Terram quae Comparetur ei. Iob. 41 . 24» («There is no power on earth to be compared to him. Job 41 . 24»)—further linking the figure to the monster of the book. (Due to disagreements over the precise location of the chapters and verses when they were divided in the Late Middle Ages, the verse Hobbes quotes is usually given as Job 41:33 in modern Christian translations into English,[8] Job 41:25 in the Masoretic text, Septuagint, and the Luther Bible; it is Job 41:24 in the Vulgate.) The torso and arms of the figure are composed of over three hundred persons, in the style of Giuseppe Arcimboldo; all are facing away from the viewer, with just the giant’s head having visible facial features. (A manuscript of Leviathan created for Charles II in 1651 has notable differences – a different main head but significantly the body is also composed of many faces, all looking outwards from the body and with a range of expressions.)

The lower portion is a triptych, framed in a wooden border. The centre form contains the title on an ornate curtain. The two sides reflect the sword and crosier of the main figure – earthly power on the left and the powers of the church on the right. Each side element reflects the equivalent power – castle to church, crown to mitre, cannon to excommunication, weapons to logic, and the battlefield to the religious courts. The giant holds the symbols of both sides, reflecting the union of secular, and spiritual in the sovereign, but the construction of the torso also makes the figure the state.

Part I: Of Man[edit]

Hobbes begins his treatise on politics with an account of human nature. He presents an image of man as matter in motion, attempting to show through example how everything about humanity can be explained materialistically, that is, without recourse to an incorporeal, immaterial soul or a faculty for understanding ideas that are external to the human mind.

Life is but a motion of limbs. For what is the heart, but a spring; and the nerves, but so many strings; and the joints, but so many wheels, giving motion to the whole body, such as was intended by the Artificer?[9]

Hobbes proceeds by defining terms clearly and unsentimentally. Good and evil are nothing more than terms used to denote an individual’s appetites and desires, while these appetites and desires are nothing more than the tendency to move toward or away from an object. Hope is nothing more than an appetite for a thing combined with an opinion that it can be had. He suggests that the dominant political theology of the time, Scholasticism, thrives on confused definitions of everyday words, such as incorporeal substance, which for Hobbes is a contradiction in terms.

Hobbes describes human psychology without any reference to the summum bonum, or greatest good, as previous thought had done. According to Hobbes, not only is the concept of a summum bonum superfluous, but given the variability of human desires, there could be no such thing. Consequently, any political community that sought to provide the greatest good to its members would find itself driven by competing conceptions of that good with no way to decide among them. The result would be civil war.

However, Hobbes states that there is a summum malum, or greatest evil. This is the fear of violent death. A political community can be oriented around this fear.

Since there is no summum bonum, the natural state of man is not to be found in a political community that pursues the greatest good. But to be outside of a political community is to be in an anarchic condition. Given human nature, the variability of human desires, and need for scarce resources to fulfill those desires, the state of nature, as Hobbes calls this anarchic condition, must be a war of all against all. Even when two men are not fighting, there is no guarantee that the other will not try to kill him for his property or just out of an aggrieved sense of honour, and so they must constantly be on guard against one another. It is even reasonable to preemptively attack one’s neighbour.

In such condition there is no place for industry, because the fruit thereof is uncertain, and consequently no culture of the earth, no navigation nor the use of commodities that may be imported by sea, no commodious building, no instruments of moving and removing such things as require much force, no knowledge of the face of the earth, no account of time, no arts, no letters, no society, and which is worst of all, continual fear and danger of violent death, and the life of man, solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short.[10]

The desire to avoid the state of nature, as the place where the summum malum of violent death is most likely to occur, forms the polestar of political reasoning. It suggests a number of laws of nature, although Hobbes is quick to point out that they cannot properly speaking be called «laws», since there is no one to enforce them. The first thing that reason suggests is to seek peace, but that where peace cannot be had, to use all of the advantages of war.[11] Hobbes is explicit that in the state of nature nothing can be considered just or unjust, and every man must be considered to have a right to all things.[12] The second law of nature is that one ought to be willing to renounce one’s right to all things where others are willing to do the same, to quit the state of nature, and to erect a commonwealth with the authority to command them in all things. Hobbes concludes Part One by articulating an additional seventeen laws of nature that make the performance of the first two possible and by explaining what it would mean for a sovereign to represent the people even when they disagree with the sovereign.

Part II: Of Commonwealth[edit]

The purpose of a commonwealth is given at the start of Part II:

THE final cause, end, or design of men (who naturally love liberty, and dominion over others) in the introduction of that restraint upon themselves, in which we see them live in Commonwealths, is the foresight of their own preservation, and of a more contented life thereby; that is to say, of getting themselves out from that miserable condition of war which is necessarily consequent, as hath been shown, to the natural passions of men when there is no visible power to keep them in awe, and tie them by fear of punishment to the performance of their covenants…

The commonwealth is instituted when all agree in the following manner: I authorise and give up my right of governing myself to this man, or to this assembly of men, on this condition; that thou give up, thy right to him, and authorise all his actions in like manner.

The sovereign has twelve principal rights:[13]

- Because a successive covenant cannot override a prior one, the subjects cannot (lawfully) change the form of government.

- Because the covenant forming the commonwealth results from subjects giving to the sovereign the right to act for them, the sovereign cannot possibly breach the covenant; and therefore the subjects can never argue to be freed from the covenant because of the actions of the sovereign.

- The sovereign exists because the majority has consented to his rule; the minority have agreed to abide by this arrangement and must then assent to the sovereign’s actions.

- Every subject is author of the acts of the sovereign: hence the sovereign cannot injure any of his subjects and cannot be accused of injustice.

- Following this, the sovereign cannot justly be put to death by the subjects.

- The purpose of the commonwealth is peace, and the sovereign has the right to do whatever he thinks necessary for the preserving of peace and security and prevention of discord. Therefore, the sovereign may judge what opinions and doctrines are averse, who shall be allowed to speak to multitudes, and who shall examine the doctrines of all books before they are published.

- To prescribe the rules of civil law and property.

- To be judge in all cases.

- To make war and peace as he sees fit and to command the army.

- To choose counsellors, ministers, magistrates and officers.

- To reward with riches and honour or to punish with corporal or pecuniary punishment or ignominy.

- To establish laws about honour and a scale of worth.

Hobbes explicitly rejects the idea of Separation of Powers. In item 6 Hobbes is explicitly in favour of censorship of the press and restrictions on the rights of free speech should they be considered desirable by the sovereign to promote order.

Types[edit]

There are three (monarchy, aristocracy and democracy):

The difference of Commonwealths consisted in the difference of the sovereign, or the person representative of all and every one of the multitude. And because the sovereignty is either in one man, or in an assembly of more than one; and into that assembly either every man hath right to enter, or not every one, but certain men distinguished from the rest; it is manifest there can be but three kinds of Commonwealth. For the representative must needs be one man, or more; and if more, then it is the assembly of all, or but of a part. When the representative is one man, then is the Commonwealth a monarchy; when an assembly of all that will come together, then it is a democracy, or popular Commonwealth; when an assembly of a part only, then it is called an aristocracy.

And only three; since unlike Aristotle he does not sub-divide them into «good» and «deviant»:

Other kind of Commonwealth there can be none: for either one, or more, or all, must have the sovereign power (which I have shown to be indivisible) entire. There be other names of government in the histories and books of policy; as tyranny and oligarchy; but they are not the names of other forms of government, but of the same forms misliked. For they that are discontented under monarchy call it tyranny; and they that are displeased with aristocracy call it oligarchy: so also, they which find themselves grieved under a democracy call it anarchy, which signifies want of government; and yet I think no man believes that want of government is any new kind of government: nor by the same reason ought they to believe that the government is of one kind when they like it, and another when they mislike it or are oppressed by the governors.

And monarchy is the best, on practical grounds:

The difference between these three kinds of Commonwealth consisteth not in the difference of power, but in the difference of convenience or aptitude to produce the peace and security of the people; for which end they were instituted. And to compare monarchy with the other two, we may observe: first, that whosoever beareth the person of the people, or is one of that assembly that bears it, beareth also his own natural person. And though he be careful in his politic person to procure the common interest, yet he is more, or no less, careful to procure the private good of himself, his family, kindred and friends; and for the most part, if the public interest chance to cross the private, he prefers the private: for the passions of men are commonly more potent than their reason. From whence it follows that where the public and private interest are most closely united, there is the public most advanced. Now in monarchy the private interest is the same with the public. The riches, power, and honour of a monarch arise only from the riches, strength, and reputation of his subjects. For no king can be rich, nor glorious, nor secure, whose subjects are either poor, or contemptible, or too weak through want, or dissension, to maintain a war against their enemies; whereas in a democracy, or aristocracy, the public prosperity confers not so much to the private fortune of one that is corrupt, or ambitious, as doth many times a perfidious advice, a treacherous action, or a civil war.

Succession[edit]

The right of succession always lies with the sovereign. Democracies and aristocracies have easy succession; monarchy is harder:

The greatest difficulty about the right of succession is in monarchy: and the difficulty ariseth from this, that at first sight, it is not manifest who is to appoint the successor; nor many times who it is whom he hath appointed. For in both these cases, there is required a more exact ratiocination than every man is accustomed to use.

Because in general people haven’t thought carefully. However, the succession is definitely in the gift of the monarch:

As to the question who shall appoint the successor of a monarch that hath the sovereign authority… we are to consider that either he that is in possession has right to dispose of the succession, or else that right is again in the dissolved multitude. … Therefore it is manifest that by the institution of monarchy, the disposing of the successor is always left to the judgement and will of the present possessor.

But, it is not always obvious who the monarch has appointed:

And for the question which may arise sometimes, who it is that the monarch in possession hath designed to the succession and inheritance of his power

However, the answer is:

it is determined by his express words and testament; or by other tacit signs sufficient.

And this means:

By express words, or testament, when it is declared by him in his lifetime, viva voce, or by writing; as the first emperors of Rome declared who should be their heirs.

Note that (perhaps rather radically) this does not have to be any blood relative:

For the word heir does not of itself imply the children or nearest kindred of a man; but whomsoever a man shall any way declare he would have to succeed him in his estate. If therefore a monarch declare expressly that such a man shall be his heir, either by word or writing, then is that man immediately after the decease of his predecessor invested in the right of being monarch.

However, practically this means:

But where testament and express words are wanting, other natural signs of the will are to be followed: whereof the one is custom. And therefore where the custom is that the next of kindred absolutely succeedeth, there also the next of kindred hath right to the succession; for that, if the will of him that was in possession had been otherwise, he might easily have declared the same in his lifetime…

Religion[edit]

In Leviathan, Hobbes explicitly states that the sovereign has authority to assert power over matters of faith and doctrine and that if he does not do so, he invites discord. Hobbes presents his own religious theory but states that he would defer to the will of the sovereign (when that was re-established: again, Leviathan was written during the Civil War) as to whether his theory was acceptable. Hobbes’ materialistic presuppositions also led him to hold a view which was considered highly controversial at the time. Hobbes rejected the idea of incorporeal substances and subsequently argued that even God himself was a corporeal substance. Although Hobbes never explicitly stated he was an atheist, many allude to the possibility that he was.

Taxation[edit]

Hobbes also touched upon the sovereign’s ability to tax in Leviathan, although he is not as widely cited for his economic theories as he is for his political theories.[14] Hobbes believed that equal justice includes the equal imposition of taxes. The equality of taxes doesn’t depend on equality of wealth, but on the equality of the debt that every man owes to the commonwealth for his defence and the maintenance of the rule of law.[15] Hobbes also championed public support for those unable to maintain themselves by labour, which would presumably be funded by taxation. He advocated public encouragement of works of Navigation etc. to usefully employ the poor who could work.

Part III: Of a Christian Commonwealth[edit]

In Part III Hobbes seeks to investigate the nature of a Christian commonwealth. This immediately raises the question of which scriptures we should trust, and why. If any person may claim supernatural revelation superior to the civil law, then there would be chaos, and Hobbes’ fervent desire is to avoid this. Hobbes thus begins by establishing that we cannot infallibly know another’s personal word to be divine revelation:

When God speaketh to man, it must be either immediately or by mediation of another man, to whom He had formerly spoken by Himself immediately. How God speaketh to a man immediately may be understood by those well enough to whom He hath so spoken; but how the same should be understood by another is hard, if not impossible, to know. For if a man pretend to me that God hath spoken to him supernaturally, and immediately, and I make doubt of it, I cannot easily perceive what argument he can produce to oblige me to believe it.

This is good, but if applied too fervently would lead to all the Bible being rejected. So, Hobbes says, we need a test: and the true test is established by examining the books of scripture, and is:

So that it is manifest that the teaching of the religion which God hath established, and the showing of a present miracle, joined together, were the only marks whereby the Scripture would have a true prophet, that is to say, immediate revelation, to be acknowledged; of them being singly sufficient to oblige any other man to regard what he saith.

Seeing therefore miracles now cease, we have no sign left whereby to acknowledge the pretended revelations or inspirations of any private man; nor obligation to give ear to any doctrine, farther than it is conformable to the Holy Scriptures, which since the time of our Saviour supply the place and sufficiently recompense the want of all other prophecy

«Seeing therefore miracles now cease» means that only the books of the Bible can be trusted. Hobbes then discusses the various books which are accepted by various sects, and the «question much disputed between the diverse sects of Christian religion, from whence the Scriptures derive their authority». To Hobbes, «it is manifest that none can know they are God’s word (though all true Christians believe it) but those to whom God Himself hath revealed it supernaturally». And therefore «The question truly stated is: by what authority they are made law?»

Unsurprisingly, Hobbes concludes that ultimately there is no way to determine this other than the civil power:

He therefore to whom God hath not supernaturally revealed that they are His, nor that those that published them were sent by Him, is not obliged to obey them by any authority but his whose commands have already the force of laws; that is to say, by any other authority than that of the Commonwealth, residing in the sovereign, who only has the legislative power.

He discusses the Ten Commandments, and asks «who it was that gave to these written tables the obligatory force of laws. There is no doubt but they were made laws by God Himself: but because a law obliges not, nor is law to any but to them that acknowledge it to be the act of the sovereign, how could the people of Israel, that were forbidden to approach the mountain to hear what God said to Moses, be obliged to obedience to all those laws which Moses propounded to them?» and concludes, as before, that «making of the Scripture law, belonged to the civil sovereign.»

Finally: «We are to consider now what office in the Church those persons have who, being civil sovereigns, have embraced also the Christian faith?» to which the answer is: «Christian kings are still the supreme pastors of their people, and have power to ordain what pastors they please, to teach the Church, that is, to teach the people committed to their charge.»

There is an enormous amount of biblical scholarship in this third part. However, once Hobbes’ initial argument is accepted (that no-one can know for sure anyone else’s divine revelation) his conclusion (the religious power is subordinate to the civil) follows from his logic. The very extensive discussions of the chapter were probably necessary for its time. The need (as Hobbes saw it) for the civil sovereign to be supreme arose partly from the many sects that arose around the civil war, and to quash the Pope of Rome’s challenge, to which Hobbes devotes an extensive section.

Part IV: Of the Kingdom of Darkness[edit]

Hobbes named Part IV of his book «Kingdom of Darkness». By this Hobbes does not mean Hell (he did not believe in Hell or Purgatory),[16] but the darkness of ignorance as opposed to the light of true knowledge. Hobbes’ interpretation is largely unorthodox and so sees much darkness in what he sees as the misinterpretation of Scripture.

- This considered, the kingdom of darkness… is nothing else but a confederacy of deceivers that, to obtain dominion over men in this present world, endeavour, by dark and erroneous doctrines, to extinguish in them the light…[17]

Hobbes enumerates four causes of this darkness.

The first is by extinguishing the light of scripture through misinterpretation. Hobbes sees the main abuse as teaching that the kingdom of God can be found in the church, thus undermining the authority of the civil sovereign. Another general abuse of scripture, in his view, is the turning of consecration into conjuration, or silly ritual.

The second cause is the demonology of the heathen poets: in Hobbes’s opinion, demons are nothing more than constructs of the brain. Hobbes then goes on to criticize what he sees as many of the practices of Catholicism: «Now for the worship of saints, and images, and relics, and other things at this day practiced in the Church of Rome, I say they are not allowed by the word of God».

The third is by mixing with the Scripture diverse relics of the religion, and much of the vain and erroneous philosophy of the Greeks, especially of Aristotle. Hobbes has little time for the various disputing sects of philosophers and objects to what people have taken «From Aristotle’s civil philosophy, they have learned to call all manner of Commonwealths but the popular (such as was at that time the state of Athens), tyranny». At the end of this comes an interesting section (darkness is suppressing true knowledge as well as introducing falsehoods), which would appear to bear on the discoveries of Galileo Galilei. «Our own navigations make manifest, and all men learned in human sciences now acknowledge, there are antipodes» (i.e., the Earth is round) «…Nevertheless, men… have been punished for it by authority ecclesiastical. But what reason is there for it? Is it because such opinions are contrary to true religion? That cannot be, if they be true.» However, Hobbes is quite happy for the truth to be suppressed if necessary: if «they tend to disorder in government, as countenancing rebellion or sedition? Then let them be silenced, and the teachers punished» – but only by the civil authority.

The fourth is by mingling with both these, false or uncertain traditions, and feigned or uncertain history.

Hobbes finishes by inquiring who benefits from the errors he diagnoses:

- Cicero maketh honourable mention of one of the Cassii, a severe judge amongst the Romans, for a custom he had in criminal causes, when the testimony of the witnesses was not sufficient, to ask the accusers, cui bono; that is to say, what profit, honour, or other contentment the accused obtained or expected by the fact. For amongst presumptions, there is none that so evidently declareth the author as doth the benefit of the action.

Hobbes concludes that the beneficiaries are the churches and churchmen.

See also[edit]

- Behemoth by Thomas Hobbes

- Classical republicanism

- John Locke

- Scientia potentia est

- Hobbes’s moral and political philosophy

References[edit]

- ^ a b Glen Newey, Routledge Philosophy GuideBook to Hobbes and Leviathan, Routledge, 2008, p. 18.

- ^ «Leviathan, sive, de materia, forma, & potestate civitatis ecclesiasticae et civilis». 1668.

- ^ Thomas Hobbes: Leviathan – Oxford University Press.

- ^ Thomas, Hobbes (2006). Thomas Hobbes : Leviathan. Rogers, G. A. J.,, Schuhmann, Karl (A critical ed.). London: Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 12. ISBN 9781441110985. OCLC 882503096.

- ^ Hilary Brown, Luise Gottsched the Translator, Camden House, 2012, p. 54.

- ^ It’s in this edition that Hobbes coined the expression auctoritas non veritas facit legem, which means «authority, not truth, makes law»: book 2, chapter 26, p. 133.

- ^ «Hobbes’s Moral and Political Philosophy». Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. 2018. (Retrieved 11 March 2009)

- ^ Job 41:33

- ^ Hobbes, Leviathan, Introduction.

- ^ Hobbes, Leviathan, XIII.9.

- ^ Hobbes, Leviathan, XIV.4.

- ^ Hobbes, Leviathan, XIII.13.

- ^ Hobbes, Leviathan, XVIII.

- ^ Aaron Levy (October 1954). «Economic Views of Thomas Hobbes». Journal of the History of Ideas. 15 (4): 589–595. doi:10.2307/2707677. JSTOR 2707677.

- ^ «Leviathan: Part II. Commonwealth; Chapters 17–31» (PDF). Early Modern Texts.

- ^ Chapter XLVI: Lastly, for the errors brought in from false or uncertain history, what is all the legend of fictitious miracles in the lives of the saints; and all the histories of apparitions and ghosts alleged by the doctors of the Roman Church, to make good their doctrines of hell and purgatory, the power of exorcism, and other doctrines which have no warrant, neither in reason nor Scripture; as also all those traditions which they call the unwritten word of God; but old wives’ fables?

- ^ «Chapter XLIV». Archived from the original on 3 August 2004. Retrieved 27 September 2004.

Further reading[edit]

Editions of Leviathan[edit]

- Leviathan. Revised Edition, eds. A.P. Martinich and Brian Battiste. Peterborough, ON: Broadview Press, 2010. ISBN 978-1-55481-003-1.[1] Archived 6 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- Leviathan: Or the Matter, Forme, and Power of a Commonwealth Ecclesiasticall and Civill, ed. by Ian Shapiro (Yale University Press; 2010).

- Leviathan, Critical edition by Noel Malcolm in three volumes: 1. Editorial Introduction; 2 and 3. The English and Latin Texts, Oxford University Press, 2012 (Clarendon Edition of the Works of Thomas Hobbes).

Critical studies[edit]

- Bagby, Laurie M. Hobbes’s Leviathan : Reader’s Guide, New York: Continuum, 2007.

- Baumrin, Bernard Herbert (ed.) Hobbes’s Leviathan – interpretation and criticism Belmont, CA: Wadsworth, 1969.

- Cranston, Maurice. «The Leviathan» History Today (Oct 1951) 1#10 pp. 17–21

- Harrison, Ross. Hobbes, Locke, and Confusion’s Masterpiece: an Examination of Seventeenth-Century Political Philosophy. Cambridge University Press, 2003.

- Hood, Francis Campbell. The divine politics of Thomas Hobbes – an interpretation of Leviathan, Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1964.

- Johnston, David. The rhetoric of Leviathan – Thomas Hobbes and the politics of cultural transformation, Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1986.

- Newey, Glen. Routledge Philosophy Guidebook to Hobbes and Leviathan, New York: Routledge, 2008.

- Rogers, Graham Alan John. Leviathan – contemporary responses to the political theory of Thomas Hobbes Bristol: Thoemmes Press, 1995.

- Schmitt, Carl. The Leviathan in the state theory of Thomas Hobbes – meaning and failure of a political symbol, Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2008 (earlier: Greenwood Press, 1996).

- Springborg, Patricia. The Cambridge Companion to Hobbes’s Leviathan, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007.

- Windolph, Francis Lyman. Leviathan and natural law, Princeton NJ: Princeton University Press, 1951.

- Zagorin, Perez. Hobbes and the Law of Nature, Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2009.

External links[edit]

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Leviathan.

Wikisource has original text related to this article:

- Reprint from the 1651 edition

- Leviathan at Project Gutenberg

Leviathan public domain audiobook at LibriVox

- Full text online at oregonstate.edu

- A reduced version of Leviathan at earlymoderntexts.com

- Scan of 1651 edition

| Левиафан, или Материя, форма и власть государства церковного и гражданского | |

| Leviathan or The Matter, Forme and Power of a Common Wealth Ecclesiasticall and Civil | |

|

|

|

| Автор: |

Томас Гоббс |

|---|---|

| Язык оригинала: |

английский |

| Носитель: |

бумага |

«Левиафан, или Материя, форма и власть государства церковного и гражданского» — название сочинения английского философа Т. Гоббса, посвящённого проблемам государства.

Левиафан — библейское чудовище, изображённое как сила природы, принижающая человека. Гоббс использует этот образ для описания могущественного государства («смертного Бога»).

При создании теории возникновения государства Гоббс отталкивается от постулата о естественном состоянии людей «Война всех против всех» (лат. Bellum omnium contra omnes) и развивает идею «Человек человеку — волк» (Homos homini lupus est).

Люди, в связи с неминуемым истреблением при нахождении в таком состоянии продолжительное время, для сохранения своих жизней и общего мира отказываются от части своих «естественных прав» и по негласно заключаемому общественному договору наделяют ими того, кто обязуется сохранить свободное использование оставшимися правами — государство.

Государству, союзу людей, в котором воля одного (государства) является обязательной для всех, передаётся задача регулирования отношений между всеми людьми.

«Левиафан» в своё время был запрещён в Англии; перевод «Левиафана» на русский язык был сожжён.

В 1868 году на русский язык был переведён Автократовым С. П.

Реминесценции

- В романе Дэна Симмонса «Террор» (2007) Крозье на проповедях иногда читал на память главы из «Левиафана», называя его «Книгой Левиафана».

Литература

- Юридическая энциклопедия / Отв. ред. Б. Н. Топорнин. — М.: Юристъ, 2001. ISBN 5-7975-0429-4.

- Малый энциклопедический словарь Брокгауза и Ефрона.

- Большая советская энциклопедия. — Издательство «Советская энциклопедия». 1970—1977.

- Иллюстрированный энциклопедический словарь. Издательство: Большая Российская энциклопедия, Оникс; 2000. ISBN 5-85270-313-3.

| |

|

|---|---|

| Научные дисциплины и теории | Политология • Сравнительная политология • Теория государства и права • Теория общественного выбора |

| Общие принципы и понятия | Гражданское общество • Правовое государство • Права человека • Разделение властей • Революция • Типы государства • Суверенитет |

| государства по политической силе и влиянию |

Великая держава • Колония • Марионеточное государство • Сателлит • Сверхдержава |

| Виды политики | Геополитика • Внутренняя политика • Внешняя политика |

| Форма государственного устройства | Конфедерация • Унитарное государство • Федерация |

| Социально-политические институты и ветви власти |

Банковская система • Верховная власть • Законодательная власть • Избирательная система • Исполнительная власть • СМИ • Судебная власть |

| Государственный аппарат и органы власти |

Глава государства • Парламент • Правительство |

| Политический режим | Анархия • Авторитаризм • Демократия • Деспотизм • Тоталитаризм |

| Форма государственного правления и политическая система |

Военная диктатура • Диктатура • Монархия • Плутократия • Парламентская республика • Республика • Теократия • Тимократия • Самодержавие • |

| Политическая философия, идеология и доктрина |

Анархизм • Коммунизм • Колониализм • Консерватизм • Космополитизм • Либерализм • Либертарианство • Марксизм • Милитаризм • Монархизм • Нацизм • Национализм • Неоколониализм • Пацифизм • Социализм • Фашизм |

| Избирательная система | Мажоритарная • Пропорциональная • Смешанная |

| Политологи и политические мыслители |

Платон • Аристотель • Макиавелли • Монтескье • Руссо • Бенито Муссолини • Гоббс • Локк • Карл Маркс • Михаил Бакунин • Макс Вебер • Морис Дюверже • Юлиус Эвола • Цицерон • Адольф Гитлер |

| Учебники и известные труды о политике |

«Государство» • «Политика» • «О граде Божьем» • «Государь» • «Левиафан» • «Открытое общество и его враги» |

| См. также | Основные понятия политики |

|

|

Название: Левиафан

Автор: Гоббс Томас

М.: Мысль, 2001. — 478 с.

ISBN 5-244-00966-4

Серия Из классического наследия

Формат: DjVu, PDF

Качество: сканированные страницы

Язык: Русский

Томас Гоббс (1588—1679) — классик политической и правовой мысли, выдающийся английский философ. В своем основном произведении «Левиафан» впервые в Новое время разработал систематическое учение о государстве и праве. Оно оказало серьезное влияние на развитие общественной мысли Европы и до сих пор остается источником оригинальных социальных идей. Предлагаемый читателю текст наиболее близок к первому английскому изданию.

От издателей

Сочинение Томаса Гоббса (1588—1679) «Левиафан, или Материя, форма и власть государства церковного и гражданского» вышло на английском языке в Лондоне ровно 350 лет назад — в 1651 г. На обложке было дано символическое изображение государства-Левиафана: словно вырастая из земли, надо всем возвышается коронованный гигант, тело которого составлено из множества маленьких фигурок людей, взоры которых обращены на лицо гиганта; в чертах этого лица угадывается сходство с Кромвелем. Наверху приведены слова из книги 41 Иова: «Нет на земле подобного ему». Само сочинение, содержавшее полное и систематическое изложение социально-политической теории Гоббса и ее философское обоснование, было задумано как апология государственной власти. Этому служило уже уподобление государства Левиафану — библейскому чудовищу, сильнее которого ничего нет и которое, согласно Библии, есть «царь над всеми сынами гордости» (Иов. 41, 26). Поднять авторитет гражданской власти и обосновать необходимость повиновения ей со стороны всех подданных — очевидная цель автора, и он достигает ее на основании собственной теории происхождения государства.

Гоббса критиковали многие. Клерикалы — за непризнание государства божественным установлением, роялисты — за неприятие монархического абсолютизма, радикальные представители теории общественного договора — за отрицание народного суверенитета, сторонники буржуазной демократической политической мысли — за отказ от принципа разделения властей, марксистские философы — за консерватизм и идеализм в понимании общества. Кроме того, исследователи творчества мыслителя, как правило, объясняли факт изменения Гоббсом его политической позиции и длительную эмиграцию из Англии главным образом свойствами его характера и желанием приспособиться к изменяющейся ситуации в стране. Гоббс, действительно примкнувший сначала к аристократии, все-таки порвал с роялистами, с одобрением отнесся к индепендентской республике, затем — к протекторату Кромвеля, а после реставрации Стюартов выразил лояльность монархии. Оценка видимых идейных колебаний Гоббса, как и отдельных положений его учения, не может быть однозначной, но многие выводы его критиков оказываются несостоятельными в свете главной идеи философа.

В 1668 г. Гоббс опубликовал свои произведения, написанные на латинском языке. В это издание он включил и собственный перевод «Левиафана» под названием «Leviathan, sive de materia, forma et potestate civitatis eccleeiastice et civilis». Английскому «commonwealth» здесь, как видим, соответствует «civitas»; в тексте фигурирует также термин «civitas popularis» (близкий по смыслу английскому commonwealth), но чаще более созвучный духу времени — monarchia.

Однако суть учения осталась неизменной, как не изменилось в латинском издании и символическое изображение государства-Левиафана, если не считать того, что лицом он стал теперь походить на Карла II. Кроме того, латинское издание отличается от английского тем, что в нем вместо «Обозрения и заключения» даны три новых главы — «О Никейском символе веры», «О ереси» и «О некоторых возражениях против «Левиафана»»,— в которых автор излагает ряд положений своей теории в соответствии с официальной идеологией монархии.

В начале 80-х гг. XVII в., через три с половиной года после смерти Гоббса, «Левиафан» и другое произведение философа — «О гражданине»— были включены в индекс запрещенных книг, составленный Оксфордским университетом (который Гоббс в свое время окончил), и сожжены. В России русский перевод «Левиафана» впервые появился в 1864 г. и был конфискован царской цензурой. В советское время перевод сочинения вышел в 1936 г., затем — в серии «Философское наследие» издательства «Мысль» — в 1964 и 1991 гг. В последнем из этих изданий были впервые переведены значительные фрагменты, посвященные толкованию Священного Писания и ранее в переводах опускавшиеся.

Настоящий текст дается по изданию 1991 г., однако без Приложения, содержащего перевод с латинского трех вышеперечисленных глав, теоретически не заключающих в себе ничего нового и написанных лишь в связи с конкретной политической ситуацией, и без «форточек», которые были воспроизведены тогда по английскому изданию 1839 г. и текст которых принадлежал издателю У. Моллесуорту. Таким образом, настоящее издание оказывается наиболее близким первому английскому изданию сочинения.

ОГЛАВЛЕНИЕ

ЛЕВИАФАН, ИЛИ МАТЕРИЯ, ФОРМА И ВЛАСТЬ ГОСУДАРСТВА ЦЕРКОВНОГО И ГРАЖДАНСКОГО. Пер. А. Гутермана

ВВЕДЕНИЕ

ЧАСТЬ I. О человеке

ГЛАВА I. Об ощущении

ГЛАВА II. О представлении

ГЛАВА III. О последовательности, или связи, представлений

ГЛАВА IV. О речи

ГЛАВА V. О рассуждении и научном знании

ГЛАВА VI. О внутренних началах произвольных движений, обычно называемых страстями, и о речах, при помощи которых они выражаются

ГЛАВА VII. О целях или результатах рассуждений

ГЛАВА VIII. О достоинствах, обычно называемых интеллектуальными, и о противостоящих им недостатках

ГЛАВА IX. О различных предметах знания

ГЛАВА X. О могуществе, ценности, достоинстве, уважении и достойности

ГЛАВА XI. О различии манер

ГЛАВА XII. О религии

ГЛАВА XIII. О естественном состоянии человеческого рода в его отношении к счастью и бедствиям людей

ГЛАВА XIV. О первом и втором естественных законах и о договорах

ГЛАВА XV. О других естественных законах

ГЛАВА XVI. О личностях, доверителях и об олицетворенных вещах

ЧАСТЬ II. О государстве

ГЛАВА XVII. О причинах, возникновении и определении государства.

ГЛАВА XVIII. О правах суверенов в государствах, основанных на установлении

ГЛАВА XIX. О различных видах государств, основанных на установлении, и о преемственности верховной власти

ГЛАВА XX. Об отеческой и деспотической власти

ГЛАВА XXI. О свободе подданных

ГЛАВА XXII. О подвластных группах людей, политических и частных

ГЛАВА XXIII. О государственных служителях верховной власти

ГЛАВА XXIV. О питании государства и о произведении им потомства

ГЛАВА XXV. О совете

ГЛАВА XXVI. О гражданских законах

ГЛАВА XXVII. О преступлениях, оправданиях и о смягчающих вину обстоятельствах

ГЛАВА XXVIII. О наказаниях и наградах

ГЛАВА XXIX. О том, что ослабляет или ведет государство к распаду

ГЛАВА XXX. Об обязанностях суверена

ГЛАВА XXXI. О Царстве Бога при посредстве природы

ЧАСТЬ III. О христианском государстве

ГЛАВА XXXII. О принципах христианской политики

ГЛАВА XXXIII. О числе, древности, цели, авторитете и толкователях книг Священного писания

ГЛАВА XXXIV. О значении слов «дух», «ангел» и «вдохновение» в книгах Священного писания

ГЛАВА XXXV. О том, что означают в Писании слова «Царство Божие», «Святой», «Посвященный» и «Таинство»

ГЛАВА XXXVI. О Слове Божием и о пророках

ГЛАВА XXXVII. О чудесах и об их употреблении

ГЛАВА XXXVIII. О том, что понимается в Писании под словами «вечная жизнь», «ад», «спасение», «грядущий мир» и «искупление»

ГЛАВА XXXIX. О том, что понимается в Писании под словом «церковь»

ГЛАВА XL. О правах Царства Божиего при Аврааме, Моисее, первосвященниках и царях иудейских

ГЛАВА XLI. О миссии нашего Святого Спасителя

ГЛАВА XLII. О церковной власти

ГЛАВА XLIII. О том, что необходимо для принятия человека в Царство Небесное

ЧАСТЬ IV. О царстве тьмы

ГЛАВА XLIV. О духовной тьме вследствие ошибочного толкования Писания

ГЛАВА XLV. О демонологии и о других пережитках религии язычников

ГЛАВА XLVI. О тьме, проистекающей из несостоятельной философии и вымышленных традиций

ГЛАВА XLVIL. О выгоде, проистекающей от тьмы, и кому эта выгода достается

ОБОЗРЕНИЕ И ЗАКЛЮЧЕНИЕ

Укаазатель имен

Послесловие

Прежде чем говорить о теории Томаса Гоббса, предлагаем задуматься над тем спектром ассоциаций, которые у вас вызывает фраза «государство как Левиафан». Непременно у большинства читателей возникнут довольно четкие образы и однозначные определения, ведь «Левиафан» в гоббсовском значении этого слова циркулирует даже в публичном политическом дискурсе. Тем не менее, связанные с Левиафаном ассоциации – это не то же самое, а в некоторых случаях и нечто совсем противоположное оригинальной концепции Гоббса. Concepture исследует, что за философские идеи кроются за этим образом.

Философ, которого окружили волки

Прежде всего концепция государства Гоббса – это последовательность рассуждений и идей. Она многослойна и поэтому, чтобы правильно воспринять теорию в целом, нужно ознакомится с её составными частями. Причем, даже если кому-то придется не по вкусу итог, многие из элементов концепта Левиафана можно рассмотреть в отрыве и восхититься по отдельности. Так, например, эту теорию воспринимают сторонники либерализма, для которых философ Гоббс, с одной стороны, – предтеча и прародитель этого политического течения, а с другой – мыслитель, в какой-то момент сворачивающий в неверную сторону.

В естественном состоянии человек предоставлен своей природе, ничем не ограниченной. И взгляд Гоббса на эту природу мрачен. По его мнению, чуть ли не единственное к чему она может привести, так это к войне всех против всех. Когда человека ничто не сдерживает, он скорее стремится обобрать и устранить другого, а не наладить контакт и договориться. Причиной такого поведения является страх перед тем, что другой человек может сделать то же самое. Таким образом, страх – это последствие свободы действий и понимания её наличия у других.

Возникает замкнутая система. Человеческая сущность базируется на эгоизме и страхе, которые вынуждают человека ожесточиться, что в свою очередь дает основание для опасения других.

«Пока люди живут без общей власти, держащей всех их в страхе, они находятся в том состоянии, которое называется войной, и именно в состоянии войны всех против всех».

Казалось бы, что на этой тотальной войне всех против всех и должна была закончится человеческая история, но всё же у человека также есть то, что не позволяет ему снизойти до животного уровня – разум. По Гоббсу, финальная компонента человеческой сущности, подогреваемая страхом, сподвигает людей призадуматься о том, как бы создать нечто, что позволит отсрочить незавидную участь пасть от жестокости другого человека.

В рамках номинализма Гоббса тот конкретный человек, в котором воплощена власть, не лишается своей эгоистической природы. Право не совершает существенной трансформации природы человека, оно дает коррективы поведению, порождая тем самым, по сути, новые формы страха – попасть в тюрьму, лишиться работы, имущества или репутации. Причем присутствие таких страхов обосновано тем, что они имеют позитивную сторону – защиту законом.

Можно заметить, что в действительности к людям у власти применяют куда более высокие моральные стандарты. Считается само собой разумеющимся, что президент куда более обязан быть добродетельным, нежели медийная личность, которой и вовсе позволено быть скандальной. Можно сказать, что по Гоббсу, это скорее специфическое выражения страха перед тем, что правителя в конечном счете ничто не заставляет исполнять предписанные ему добродетели.

Говоря о сущности человеческого страха, Гоббс в том числе предполагает, что важную роль в формировании «бесконечного» ужаса играет Бог, который является непознаваемым и при том фундаментальным. Получается, что человек заворожен и устрашен.

Естественное состояние между тем подразумевает и доюридическое равенство людей ввиду «права на всё». Каждый индивид примерно с одинаковым успехом может навредить другому. Поэтому равенство для Гоббса естественно, хоть и обременительно.

Стоит понимать, что в рассуждении Гоббса о естественном состоянии и войне всех против всех важно не то, как это было (или не было), а то, во что это выливается в мирное и стабильное время. Между людьми всегда существует недоверие и ожидание враждебности, которые не только заставляют их закрывать дом на ключ, но и ставить сигнализацию, а на всякий случай ещё и завести собаку. Даже ежедневные, рутинные и бытовые практики полны опасений насчет доброжелательности других людей.

Lupus Sapiens

Разум подсказывает человеку, что избежать постоянного страха можно с помощью договоренности с другими людьми о том, чтобы пожертвовать некоторыми своими правами. В понимании Гоббса общественный договор возникает именно между людьми, которые уже только после этого становятся обществом. Возможно, такой вывод Гоббс делал на основе истории и реалий XVII века, где складывались различные не-государственные общности посредством гласного или не очень соглашения людей – монастырские и рыцарские ордена, цеха и гильдии, торговые сообщества, клубы.