| The Lion King | |

|---|---|

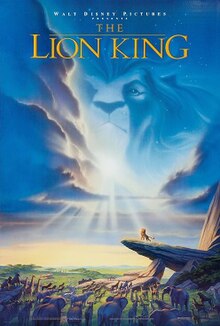

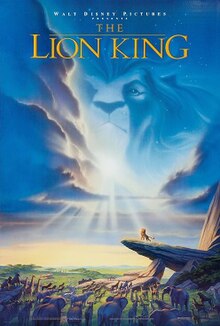

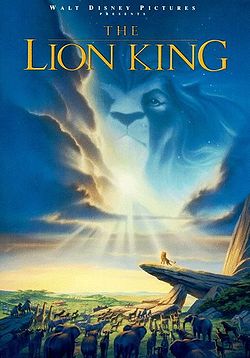

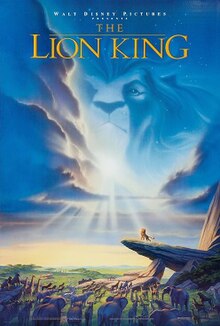

Theatrical release poster by John Alvin |

|

| Directed by |

|

| Screenplay by |

|

| Story by |

|

| Produced by | Don Hahn |

| Starring |

|

| Edited by | Ivan Bilancio |

| Music by | Hans Zimmer |

|

Production |

|

| Distributed by | Buena Vista Pictures Distribution |

|

Release date |

|

|

Running time |

88 minutes[1] |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $45 million[2] |

| Box office | $968.5 million[3] |

The Lion King is a 1994 American animated musical drama film[4] produced by Walt Disney Feature Animation and released by Walt Disney Pictures. The 32nd Disney animated feature film and the fifth produced during the Disney Renaissance, it is inspired by William Shakespeare’s Hamlet with elements from the Biblical stories of Joseph and Moses and Disney’s 1942 film Bambi. The film was directed by Roger Allers and Rob Minkoff (in their feature directorial debuts) and produced by Don Hahn, from a screenplay written by Irene Mecchi, Jonathan Roberts, and Linda Woolverton. The film features an ensemble voice cast that includes Matthew Broderick, James Earl Jones, Jeremy Irons, Jonathan Taylor Thomas, Nathan Lane, Ernie Sabella, Rowan Atkinson and Robert Guillaume. Its original songs were written by composer Elton John and lyricist Tim Rice, with a score by Hans Zimmer.

Set in a kingdom of lions in Africa, The Lion King tells the story of Simba (Swahili for lion), a lion cub who is to succeed his father, Mufasa, as King of the Pride Lands; however, after his paternal uncle Scar kills Mufasa to seize the throne, Simba is tricked into believing he was responsible for his father’s death and flees into exile. After growing up in the company of the carefree outcasts Timon and Pumbaa, Simba receives valuable perspective from his childhood friend, Nala, and his shaman, Rafiki, before returning to challenge Scar to end his tyranny and take his place in the Circle of Life as the rightful king.

The Lion King was released on June 15, 1994, receiving critical acclaim for its music, story, themes, and animation. With an initial worldwide gross of $763 million, it finished its theatrical run as the highest-grossing film of 1994 and the second-highest-grossing film of all time, behind Jurassic Park (1993).[5] It also held the title of the highest-grossing animated film, until it was overtaken by Finding Nemo (2003). The film remains the highest-grossing traditionally animated film of all time, as well as the best-selling film on home video, having sold over 55 million copies worldwide. It received two Academy Awards, as well as the Golden Globe Award for Best Motion Picture – Musical or Comedy.

The film has led to many derived works, such as a Broadway adaptation in 1997; two direct-to-video follow-ups—the sequel, The Lion King II: Simba’s Pride (1998), and the prequel/parallel, The Lion King 1½ (2004); two television series, Timon and Pumbaa and The Lion Guard; and a photorealistic remake in 2019, which also became the highest-grossing animated film at the time of its release. In 2016, the film was selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry by the Library of Congress as being «culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant».[6] The Lion King is the first Disney film to have been dubbed in Zulu,[7] and the only African language aside from Arabic to have been used for a feature-length Disney dub.[8]

Plot[edit]

In the Pride Lands of Africa, a pride of lions rule over the kingdom from Pride Rock. King Mufasa and Queen Sarabi’s newborn son, Simba, is presented to the gathering animals by Rafiki the mandrill, the kingdom’s shaman and advisor. Mufasa’s younger brother, Scar, covets the throne.

After Simba grows into a cub, Mufasa shows him the Pride Lands and explains the responsibilities of kingship and the «circle of life,» which connects all living things. One day, Simba and his best friend Nala explore an elephant graveyard, where the two are chased by three hyenas named Shenzi, Banzai, and Ed. Mufasa is alerted by his majordomo, the hornbill Zazu, and rescues the cubs. Though disappointed with Simba for disobeying him and putting himself and Nala in danger, Mufasa forgives him and explains that the great kings of the past watch over them from the night sky, from which he will one day watch over Simba. Scar, having planned the attack, visits the hyenas and convinces them to help him kill both Mufasa and Simba in exchange for hunting rights in the Pride Lands.

Scar sets a trap for Simba and Mufasa, luring Simba into a gorge and having the hyenas drive a large herd of wildebeest into a stampede to trample him. Mufasa saves Simba but winds up hanging perilously from the gorge’s edge; he begs for Scar’s help, but Scar throws Mufasa back into the stampede to his death. Scar tricks Simba into believing that the event was his fault and tells him to leave the kingdom and never return. Once Simba flees, Scar orders the hyenas to kill Simba, who manages to escape. Unaware of Simba’s survival, Scar tells the pride that the stampede killed both Mufasa and Simba and steps forward as the new king, allowing the hyenas into the Pride Lands.

After he collapses in a desert, Simba is rescued by two outcasts, a meerkat and warthog named Timon and Pumbaa. Simba grows up with his two new friends in their oasis, living a carefree life under their motto «hakuna matata» («no worries» in Swahili). Years later, an adult Simba rescues Timon and Pumbaa from a hungry lioness, who turns out to be Nala. Simba and Nala fall in love, and she urges him to return home, telling him that the Pride Lands have become drought-stricken under Scar’s reign. Still feeling guilty over Mufasa’s death, Simba refuses and storms off. He encounters Rafiki, who tells Simba that Mufasa’s spirit lives on in him. Simba is visited by the spirit of Mufasa in the night sky, who tells him that he must take his place as king. After Rafiki advises him to learn from the past instead of running from it, Simba decides to return to the Pride Lands.

Aided by his friends, Simba sneaks past the hyenas at Pride Rock and confronts Scar. Scar taunts Simba over his supposed role in Mufasa’s death and backs him to the edge of the rock, where he reveals to Simba that he is the one who killed Mufasa. Shattered by the revelation, an enraged Simba retaliates and forces Scar to reveal the truth to the rest of the pride. A battle breaks out, and Timon, Pumbaa, Rafiki, Zazu, and the lionesses fend off the hyenas. Scar attempts to escape, but is cornered by Simba at a ledge near the top of Pride Rock. Scar begs for mercy and blames his actions on the hyenas; Simba spares Scar’s life but, quoting what Scar told him long ago, orders Scar to leave the Pride Lands forever. Scar refuses and attacks his nephew, but after a brief battle, Simba throws him off the ledge to the ground below. Scar survives the fall, but the hyenas, who overheard him betraying them, maul him to death, ending his reign of terror.

With Scar and the hyenas gone, Simba takes his place as king and Nala becomes his queen. With the Pride Lands restored, Rafiki presents Simba and Nala’s newborn cub to the assembled animals, continuing the circle of life.

Voice cast[edit]

A promotional image of the characters from the film. From left to right: Shenzi, Scar, Ed, Banzai, Rafiki, Young Simba, Mufasa, Young Nala, Sarabi, Zazu, Sarafina, Timon, and Pumbaa.

- Matthew Broderick as Simba, son of Mufasa and Sarabi, who grows up to become King of the Pride Lands. Rock singer Joseph Williams provided adult Simba’s singing voice.[a]

- Jonathan Taylor Thomas voiced young Simba, while Jason Weaver provided the cub’s singing voice.[9]

- Jeremy Irons as Scar, Mufasa’s younger brother and rival, the film’s main antagonist, who seizes the throne. [b]

- James Earl Jones as Mufasa, Simba’s father, King of the Pride Lands as the film begins.[c]

- Moira Kelly as Nala, Simba’s best friend and later his mate and Queen of the Pride Lands. Sally Dworsky provided her singing voice.[d]

- Niketa Calame provided the voice of young Nala while Laura Williams provided her singing voice.[9]

- Nathan Lane as Timon, a wisecracking and self-absorbed yet loyal bipedal meerkat who becomes one of Simba’s best friends.[e]

- Ernie Sabella as Pumbaa, a naïve warthog who suffers from flatulence and is Timon’s best friend and also becomes one of Simba’s best friends.[f]

- Robert Guillaume as Rafiki, an old mandrill who serves as shaman of the Pride Lands and presents newborn cubs of the King and Queen to the animals of the Pride Lands.[g]

- Rowan Atkinson as Zazu, a hornbill who serves as the king’s majordomo (or «Mufasa’s little stooge», as Shenzi calls him).[h]

- Madge Sinclair as Queen Sarabi, Mufasa’s mate, Simba’s mother, and the leader of the lioness hunting party.[i]

- Whoopi Goldberg, Cheech Marin, and Jim Cummings as the three leaders of a clan of spotted hyenas, supposed «friends» of Scar who participate in his plot in the death of Mufasa and Simba.[j]

- Goldberg voices Shenzi, the sassy and short-tempered female leader of the trio.

- Marin voices Banzai, an aggressive and hot-headed hyena prone to complaining and acting on impulse.

- Cummings voices Ed, a dimwitted hyena who does not talk, only communicating through laughter.

- Cummings also voiced a mole that talks with Zazu and sang as Scar in place of Irons for certain lines of «Be Prepared».[10]

- Zoe Leader as Sarafina, Nala’s mother, who is shown briefly talking to Simba’s mother, Sarabi.

Production[edit]

Development[edit]

The idea for The Lion King is widely disputed.[11][12][13] According to Charlie Fink (then-Walt Disney Feature Animation’s vice president for creative affairs), he approached Jeffrey Katzenberg, Roy E. Disney, and Peter Schneider with a Bambi in Africa idea with lions. Katzenberg balked at the idea at first, but nevertheless encouraged Fink and his writers to develop a mythos to explain how lions serviced other animals by eating them.[14] Another anecdote states that the idea was conceived during a conversation between Katzenberg, Roy E. Disney, and Schneider on a flight to Europe during a promotional tour.[k] During the conversation, the topic of a story set in Africa came up, and Katzenberg immediately jumped at the idea.[16] Katzenberg decided to add elements involving coming of age and death, and ideas from personal life experiences, such as some of his trials in his career in politics, saying about the film, «It is a little bit about myself.»[17]

On October 11, 1988, Thomas Disch (the author of The Brave Little Toaster) had met with Fink and Roy E. Disney to discuss the idea, and within the next month, he had written a nine-paged treatment entitled King of the Kalahari.[18][19] Throughout 1989, several Disney staff writers, including Jenny Tripp, Tim Disney, Valerie West and Miguel Tejada-Flores, had written treatments for the project. Tripp’s treatment, dated on March 2, 1989, introduced the name «Simba» for the main character, who gets separated from his pride and is adopted by Kwashi, a baboon, and Mabu, a mongoose. He is later raised in a community of baboons. Simba battles an evil jackal named Ndogo, and reunites with his pride.[20] Later that same year, Fink recruited his friend J. T. Allen, a writer, to develop new story treatments. Fink and Allen had earlier made several trips to a Los Angeles zoo to observe the animal behavior that was to be featured in the script. Allen completed his script, which was titled The Lion King, on January 19, 1990. However, Fink, Katzenberg, and Roy E. Disney felt Allen’s script could benefit from a more experienced screenwriter, and turned to Ronald Bass, who had recently won an Academy Award for Best Original Screenplay for Rain Man (1988). At the time, Bass was preoccupied to rewrite the script himself, but agreed to supervise the revisions. The new script, credited to both Allen and Bass, was retitled King of the Beasts and completed on May 23, 1990.[20]

Sometime later, Linda Woolverton, who was also writing Beauty and the Beast (1991), spent a year writing several drafts of the script, which was titled King of the Beasts and then King of the Jungle.[21] The original version of the film was vastly different from the final product. The plot centered on a battle between lions and baboons, with Scar being the leader of the baboons, Rafiki being a cheetah,[17] and Timon and Pumbaa being Simba’s childhood friends. Simba would not only leave the kingdom but become a «lazy, slovenly, horrible character» due to manipulations from Scar, so Simba could be overthrown after coming of age.[23] By 1990, producer Thomas Schumacher, who had just completed The Rescuers Down Under (1990), decided to attach himself to the project «because lions are cool».[21] Schumacher likened the King of the Jungle script to «an animated National Geographic special».[24]

George Scribner, who had directed Oliver & Company (1988), was the initial director of the film,[25] being later joined by Roger Allers, who was the lead story man on Beauty and the Beast (1991).[16][11] Allers worked with Scribner and Woolverton on the project, but temporarily left the project to help rewrite Aladdin (1992). Eight months later, Allers returned to the project,[26][27] and brought Brenda Chapman and Chris Sanders with him.[28] In October 1991, several of the lead crew members, including Allers, Scribner, Chapman, Sanders, and Lisa Keene visited Hell’s Gate National Park in Kenya, in order to study and gain an appreciation of the environment for the film.[29][30] After six months of story development work, Scribner decided to leave the project upon clashing with Allers and the producers over their decision to turn the film into a musical, since Scribner’s intention was of making a documentary-like film more focused on natural aspects.[16][25] By April 1992, Rob Minkoff had replaced Scribner as the new co-director.[9][28]

Don Hahn joined the production as the film’s producer because Schumacher was promoted to Vice President of Development for Walt Disney Feature Animation.[31][24] Hahn found the script unfocused and lacking a clear theme, and after establishing the main theme as «leaving childhood and facing up to the realities of the world», asked for a final retool. Allers, Minkoff, Chapman, and Hahn then rewrote the story across two weeks of meetings with directors Kirk Wise and Gary Trousdale, who had finished directing Beauty and the Beast (1991).[32] One of the definite ideas that stemmed from the meetings was to have Mufasa return as a ghost. Allers also changed from the character Rafiki from a more serious court advisor into a wacky shaman.[33] The title was also changed from King of the Jungle to The Lion King, as the setting was not the jungle but the savannah.[16] It was also decided to make Mufasa and Scar brothers, as the writers felt it was much more interesting if the threat came from someone within the family.[34] Allers and Minkoff pitched the revised story to Katzenberg and Michael Eisner, to which Eisner felt the story «could be more Shakespearean»; he suggested modeling the story on King Lear. Maureen Donley, an associate producer, countered, stating that the story resembled Hamlet.[35] Continuing on the idea, Allers recalled Katzenberg asking them to «put in as much Hamlet as you can», to which they did. However, they felt it was too forced, and looked to other heroic archetypes such as the stories of Joseph and Moses from the Bible.[36]

Not counting most of the segments from Fantasia (1940), Saludos Amigos (1942), The Three Caballeros (1944), Make Mine Music (1946) and Melody Time (1948); and The Rescuers Down Under (1990) (a sequel to The Rescuers (1977)), The Lion King was the first Disney animated feature to be an original story, rather than be based on pre-existing works and characters. The filmmakers have stated that the story of The Lion King was inspired by the lives of Joseph and Moses from the Bible, and Shakespeare’s Hamlet,[34] though the story has also drawn some comparisons to Shakespeare’s lesser known plays Henry IV, Part 1 and Part 2.[37]

By this point, Woolverton had left the production to work on the Broadway adaptation of Beauty and the Beast.[9] To replace her, Allers and Minkoff met with numerous screenwriters, including Billy Bob Thornton and Joss Whedon, to discuss writing the new screenplay.[35] During the summer of 1992, Irene Mecchi was hired as the new screenwriter, and months later, she was joined by Jonathan Roberts. Mecchi and Roberts took charge of the revision process, fixing unresolved emotional issues in the script and adding comedic situations for Pumbaa, Timon, and the hyenas.[38][9] Lyricist Tim Rice worked closely with the screenwriting team, flying to California at least once a month, as his songs for the film needed to work in the narrative continuity. Rice’s lyrics—which were reworked up to the production’s end—were pinned to the storyboards during development.[39] Rewrites were frequent, with animator Andreas Deja saying that completed scenes would be delivered, only for the response to be that parts needed to be reanimated because of dialogue changes.[40]

Casting[edit]

The voice actors were chosen for how they fit and could add to the characters; for instance, James Earl Jones was cast because the directors found his voice «powerful» and similar to a lion’s roar.[41] Jones remarked that during the years of production, Mufasa «became more and more of a dopey dad instead of [a] grand king».[42]

Nathan Lane auditioned for Zazu, and Ernie Sabella for one of the hyenas. Upon meeting at the recording studio, Lane and Sabella – who were starring together in a Broadway production of Guys and Dolls at the time – were asked to record together as hyenas. The directors laughed at their performance and decided to instead cast them as Timon and Pumbaa.[41][43] For the hyenas, the original intention was to reunite Cheech & Chong, but while Cheech Marin agreed to voice Banzai, Tommy Chong was unavailable. His role was changed into a female hyena, Shenzi, voiced by Whoopi Goldberg, who insisted on being in the film. The English double act Vic Reeves and Bob Mortimer auditioned for roles as a pair of chipmunks; according to Mortimer, the producers were enthusiastic, but he and Reeves were uncomfortable with their corporate attitude and abandoned the film.[44] Rowan Atkinson was initially uninterested in the studio’s offer to voice Zazu, later explaining that «voice work is something I generally had never done and never liked […] I’m a visual artist, if I’m anything, and it seemed to be a pointless thing to do». His fellow Mr. Bean writer and actor Robin Driscoll convinced him to accept the role, and Atkinson retrospectively expressed that The Lion King became «a really, very special film».[45]

Matthew Broderick was cast as adult Simba early during production. Broderick only recorded with another actor once over the three years he worked on the film, and only learned that Moira Kelly voiced Nala at the film’s premiere.[46] English actors Tim Curry, Malcolm McDowell, Alan Rickman, Patrick Stewart, and Ian McKellen were considered for the role of Scar,[47] which eventually went to fellow Englishman Jeremy Irons.[48] Irons initially turned down the part, as he felt uncomfortable going to a comedic role after his dramatic portrayal of Claus von Bülow in Reversal of Fortune (1990). His performance in that film inspired the writers to incorporate more of his acting as von Bülow in the script – adding one of that character’s lines, «You have no idea» – and prompted animator Andreas Deja to watch Reversal of Fortune and Damage (1992) in order to incorporate Irons’ facial traits and tics.[42][49]

Animation[edit]

«The Lion King was considered a little movie because we were going to take some risks. The pitch for the story was a lion cub gets framed for murder by his uncle set to the music of Elton John. People said, ‘What? Good luck with that.’ But for some reason, the people who ended up on the movie were highly passionate about it and motivated.»

Don Hahn[43]

The development of The Lion King coincided with that of Pocahontas (1995), which most of the animators of Walt Disney Feature Animation decided to work on instead, believing it would be the more prestigious and successful of the two.[34] The story artists also did not have much faith in the project, with Chapman declaring she was reluctant to accept the job «because the story wasn’t very good»,[50] and Burny Mattinson telling his colleague Joe Ranft: «I don’t know who is going to want to watch that one.»[51][self-published source] Most of the leading animators either were doing their first major work supervising a character, or had much interest in animating an animal.[17] Thirteen of these supervising animators, both in California and in Florida, were responsible for establishing the personalities and setting the tone for the film’s main characters. The animation leads for the main characters included Mark Henn on young Simba, Ruben A. Aquino on adult Simba, Andreas Deja on Scar, Aaron Blaise on young Nala, Anthony DeRosa on adult Nala, and Tony Fucile on Mufasa.[9] Nearly twenty minutes of the film, including the «I Just Can’t Wait to Be King» sequence, was animated at the Disney-MGM Studios facility. More than 600 artists, animators, and technicians contributed to The Lion King.[25] Weeks before the film’s release, the 1994 Northridge earthquake shut down the studio and required the animators to complete via remote work.[52]

The character animators studied real-life animals for reference, as was done for Bambi (1942). Jim Fowler, renowned wildlife expert, visited the studios on several occasions with an assortment of lions and other savannah inhabitants to discuss behavior and help the animators give their drawings authenticity.[53] The animators also studied animal movements at the Miami MetroZoo under guidance from wildlife expert Ron Magill.[54] The Pride Lands are modeled on the Kenyan national park visited by the crew. Varied focal lengths and lenses were employed to differ from the habitual portrayal of Africa in documentaries—which employ telephoto lenses to shoot the wildlife from a distance. The epic feel drew inspiration from concept studies by artist Hans Bacher—who, following Scribner’s request for realism, tried to depict effects such as lens flare—and the works of painters Charles Marion Russell, Frederic Remington, and Maxfield Parrish.[55][56] Art director Andy Gaskill and the filmmakers sought to give the film a sense of grand sweep and epic scale similar to Lawrence of Arabia (1962). Gaskill explained: «We wanted audiences to sense the vastness of the savannah and to feel the dust and the breeze swaying through the grass. In other words, to get a real sense of nature and to feel as if they were there. It’s very difficult to capture something as subtle as a sunrise or rain falling on a pond, but those are the kinds of images that we tried to get.» The filmmakers also watched the films of John Ford and other filmmakers, which also influenced the design of the film.[9]

Because the characters were not anthropomorphized, all the animators had to learn to draw four-legged animals, and the story and character development was done through the use of longer shots following the characters.

Computers helped the filmmakers present their vision in new ways. For the «wildebeest stampede» sequence, several distinct wildebeest characters were created in a 3D computer program, multiplied into hundreds, cel shaded to look like drawn animation, and given randomized paths down a mountainside to simulate the real, unpredictable movement of a herd.[57] Five specially trained animators and technicians spent more than two years creating the two-and-a-half-minute stampede.[9] The Computer Animation Production System (CAPS) helped simulate camera movements such as tracking shots, and was employed in coloring, lighting, and particle effects.

Music[edit]

Lyricist Tim Rice, who was working with composer Alan Menken on songs for Aladdin (1992), was invited to write songs for The Lion King, and accepted on the condition of bringing in a composing partner. As Menken was unavailable, the producers accepted Rice’s suggestion of Elton John,[41] after Rice’s invitation of ABBA fell through due to Benny Andersson’s commitments to the stage musical Kristina från Duvemåla.[17] John expressed an interest in writing «ultra-pop songs that kids would like; then adults can go and see those movies and get just as much pleasure out of them», mentioning a possible influence of The Jungle Book (1967), where he felt the «music was so funny and appealed to kids and adults».[58]

Rice and John wrote five original songs for The Lion King («Circle of Life», «I Just Can’t Wait to Be King», «Be Prepared», «Hakuna Matata», and «Can You Feel the Love Tonight»), with John’s performance of «Can You Feel the Love Tonight» playing over the end credits.[59] The IMAX and DVD releases added another song, «The Morning Report», based on a song discarded during development that eventually featured in the live musical version of The Lion King.[60] The score was composed by Hans Zimmer, who was hired based on his earlier work on two films in African settings, A World Apart (1988) and The Power of One (1992),[61] and supplemented the score with traditional African music and choir elements arranged by Lebo M.[59] Zimmer’s partners Mark Mancina and Jay Rifkin helped with arrangements and song production.[62]

The Lion King original motion picture soundtrack was released by Walt Disney Records on April 27, 1994. It was the fourth-best-selling album of the year on the Billboard 200 and the top-selling soundtrack.[63] It is the only soundtrack to an animated film to be certified Diamond (10× platinum) by the Recording Industry Association of America. Zimmer’s complete instrumental score for the film was never originally given a full release, until the soundtrack’s commemorative twentieth anniversary re-release in 2014.[64] The Lion King also inspired the 1995 release Rhythm of the Pride Lands, with eight songs by Zimmer, Mancina, and Lebo M.[65]

The use of the song «The Lion Sleeps Tonight» in a scene with Timon and Pumbaa led to disputes between Disney and the family of South African Solomon Linda, who composed the song (originally titled «Mbube») in 1939. In July 2004, Linda’s family filed a lawsuit, seeking $1.6 million in royalties from Disney. In February 2006, Linda’s heirs reached a settlement with Abilene Music, who held the worldwide rights and had licensed the song to Disney for an undisclosed amount of money.[66]

Marketing[edit]

For The Lion King‘s first film trailer, Disney opted to feature a single scene, the entire opening sequence with the song «Circle of Life». Buena Vista Pictures Distribution president Dick Cook said the decision was made for such an approach because «we were all so taken by the beauty and majesty of this piece that we felt like it was probably one of the best four minutes of film that we’ve seen», and Don Hahn added that «Circle of Life» worked as a trailer as it «came off so strong, and so good, and ended with such a bang». The trailer was released in November 1993, accompanying The Three Musketeers (1993) and Sister Act 2: Back in the Habit (1993) in theaters; by then, only a third of The Lion King had been completed.[67][68] Audience reaction was enthusiastic, causing Hahn to have some initial concerns as he became afraid of not living up to the expectations raised by the preview.[67] Prior to the film’s release, Disney did 11 test screenings.[69]

Upon release, The Lion King was accompanied by an extensive marketing campaign which included tie-ins with Burger King, Mattel, Kodak, Nestlé, and Payless ShoeSource, and various merchandise,[70] accounting 186 licensed products.[71][72] In 1994, Disney earned approximately $1 billion with products based on the film,[73] with $214 million for Lion King toys during Christmas 1994 alone.[74]

Release[edit]

Theatrical[edit]

The Lion King had a limited release in the United States on June 15, 1994, playing in only two theaters, El Capitan Theatre in Los Angeles and Radio City Music Hall in New York City,[75] and featuring live shows with ticket prices up to $30.[76]

The wide release followed on June 24, 1994, in 2,550 screens. The digital surround sound of the film led many of those theaters to implement Dolby Laboratories’ newest sound systems.[77]

Localization[edit]

When first released in 1994, The Lion King numbered 28 versions overall in as many languages and dialects worldwide, including a special Zulu version made specifically for the film in South Africa, where a Disney USA team went to find the Zulu voice-actors. This is not just the only Zulu dubbing ever made by Disney, but also the only one made in any African language, other than Arabic.[78][79] The Lion King marks also the first time a special dubbing is released in honor of a Disney movie background, but not the last: in 2016 the film Moana (2016) received a special Tahitian language version,[80] followed in 2017 by a Māori version,[81] in 2018 by a Hawaiian version;[82] and in 2019 the film Frozen II (2019) was dubbed into Northern Sami, even though Frozen (2013) was not.[83][84] By 2022, 45 language adaptations of the film had been produced.[85] The special Zulu dubbing was made available on the streaming platform Disney+ in October 2022, together with the Māori dubbing of Moana, and the special Arapaho dubbing of Bambi.[86]

Following the success of the Māori dub of Moana, a Māori version of The Lion King was announced in 2021, and released theatrically on June 23, 2022 to align with the Māori holiday of Matariki.[87][88] Much of the Matewa Media production team, including producer Chelsea Winstanley, director Tweedie Waititi, and co-musical director Rob Ruha had previously worked on the Māori language version of Moana.[89] The Lion King Reo Māori is the first time a language adaptation has translated Elton John’s «Can You Feel the Love Tonight» for the ending credits.[85]

Home media[edit]

The Lion King was first released on VHS and LaserDisc in the United States on March 3, 1995, under Disney’s «Masterpiece Collection» video series. The VHS edition of this release contained a special preview for Walt Disney Pictures’ then-upcoming animated film Pocahontas (1995), in which the title character (voiced by Judy Kuhn) sings the musical number «Colors of the Wind».[90] In addition, Deluxe Editions of both formats were released. The VHS Deluxe Edition included the film, an exclusive lithograph of Rafiki and Simba (in some editions), a commemorative «Circle of Life» epigraph, six concept art lithographs, another tape with the half-hour TV special The Making of The Lion King, and a certificate of authenticity. The CAV laserdisc Deluxe Edition also contained the film, six concept art lithographs and The Making of The Lion King, and added storyboards, character design artwork, concept art, rough animation, and a directors’ commentary that the VHS edition did not have, on a total of four double sided discs. The VHS tape quickly became the best-selling videotape of all time: 4.5 million tapes were sold on the first day[91] and ultimately sales totaled more than 30 million[92] before these home video versions went into moratorium in 1997.[93] The VHS releases have sold a total of 32 million units in North America,[94] and grossed $520 million in sales revenue.[95] In addition, 23 million units were shipped overseas to international markets.[96] In the Philippines, the film was released on VHS in March 1995 by Magnavision.[97] The film sold more than 55 million video copies worldwide by August 1997, making it the best-selling home video title of all time.[98]

On October 7, 2003, the film was re-released on VHS and released on DVD for the first time, titled The Lion King: Platinum Edition, as part of Disney’s Platinum Edition line of DVDs. The DVD release featured two versions of the film on the first disc, a remastered version created for the 2002 IMAX release and an edited version of the IMAX release purporting to be the original 1994 theatrical version.[99] A second disc, with bonus features, was also included in the DVD release. The film’s soundtrack was provided both in its original Dolby 5.1 track and in a new Disney Enhanced Home Theater Mix, making this one of the first Disney DVDs so equipped.[100] This THX certified two-disc DVD release also contains several games, Timon and Pumbaa’s Virtual Safari, deleted scenes, music videos and other bonus features.[101] By means of seamless branching, the film could be viewed either with or without a newly created scene – a short conversation in the film replaced with a complete song («The Morning Report»). A Special Collector’s Gift Set was also released, containing the DVD set, five exclusive lithographed character portraits (new sketches created and signed by the original character animators), and an introductory book entitled The Journey.[93] The Platinum Edition of The Lion King featured changes made to the film during its IMAX re-release, including re-drawn crocodiles in the «I Just Can’t Wait to Be King» sequence as well as other alterations.[99] More than two million copies of the Platinum Edition DVD and VHS units were sold on the first day of release.[91] A DVD box set of the three The Lion King films (in two-disc Special Edition formats) was released on December 6, 2004. In January 2005, the film, along with the sequels, went back into moratorium.[102] The DVD releases have sold a total of 11.9 million units and grossed $220 million.[103]

Walt Disney Studios Home Entertainment released the Diamond Edition of The Lion King on October 4, 2011.[104] This marks the first time that the film has been released in high-definition Blu-ray and on Blu-ray 3D.[104][105] The initial release was produced in three different packages: a two-disc version with Blu-ray and DVD; a four-disc version with Blu-ray, DVD, Blu-ray 3D, and digital copy; and an eight-disc box set that also includes the sequels The Lion King II: Simba’s Pride and The Lion King 1½.[104][105] A standalone single-disc DVD release also followed on November 15, 2011.[104] The Diamond Edition topped the Blu-ray charts with over 1.5 million copies sold.[106] The film sold 3.83 million Blu-ray units in total, leading to a $101.14 million income.[107]

The Lion King was once again released to home media as part of the Walt Disney Signature Collection first released on Digital HD on August 15, 2017, and on Blu-ray and DVD on August 29, 2017.[108]

The Lion King was released on Ultra HD Blu-ray and 4K digital download on December 3, 2018.[109]

Reception[edit]

Box office[edit]

The Lion King grossed $422.8 million in North America and $545.7 million in other territories, for a worldwide total of $968.5 million.[2] After its initial run, having earned $763.5 million,[110] it ranked as the highest-grossing animated film of all time, the highest-grossing film of Walt Disney Animation Studios,[111] and the highest-grossing film of 1994.[112] It was the second-highest-grossing film of all time, behind Jurassic Park (1993).[5] The film remained as the second-highest-grossing film until the spot was taken by Independence Day (1996) just two years later.[113]

It held the record for the highest-grossing animated feature film (in North America, outside North America, and worldwide) until it was surpassed by the computer-animated Finding Nemo (2003). With the earnings of the 3D run, The Lion King surpassed all the aforementioned films but Toy Story 3 (2010) to rank as the second-highest-grossing animated film worldwide—later dropping to ninth, and then tenth, surpassed by its photorealistic CGI remake counterpart—and it remains the highest-grossing hand-drawn animated film.[114] It is also the biggest animated movie of the last 50 years in terms of estimated attendance.[115] The Lion King was also the highest-grossing G-rated film in the United States from 1994 to 2003 and again from 2011 to 2019 until its total was surpassed by the computer-animated Toy Story 4 (2019) (unadjusted for inflation).[116]

Original theatrical run[edit]

During the first two days of limited release in two theaters, The Lion King grossed $622,277, and for the weekend it earned nearly $1.6 million, placing the film in tenth place at the box office.[117] The average of $793,377 per theater stands as the largest ever achieved during a weekend,[118] and it was the highest-grossing opening weekend on under 50 screens, beating the record set by Star Wars (1977) from 43 screens.[119] The film grossed nearly $3.8 million from the two theaters in just 10 days.[120]

When it opened wide, The Lion King grossed $40.9 million—which at the time was the fourth biggest opening weekend ever and the highest sum for a Disney film—to top the weekend box office. It displaced the previous box office champion Wolf.[25][121] At that time, it easily topped the previous biggest 1994 opening, which was the $37.2 million earned by The Flintstones during the four-day Memorial Day weekend. The film also produced the third-highest opening weekend gross of any film, trailing only behind Jurassic Park (1993) and Batman Returns (1992).[122] For five years, the film held the record for having the highest opening weekend for an animated film until it was surpassed by Toy Story 2 (1999).[123] It remained the number-one box office film for two weeks until it was displaced by Forrest Gump, followed by True Lies the week after.[124]

In September 1994, Disney pulled the film from movie theaters and announced it would be re-released during Thanksgiving in order to take advantage of the holiday season.[125] At the time, the film had earned $267 million in the United States.[2][126] Following its re-release, by March 1995, it had grossed $312.9 million,[2] being the highest-grossing 1994 film in the United States and Canada, but was soon surpassed by Forrest Gump.[127] Box Office Mojo estimates that the film sold over 74 million tickets in the US in its initial theatrical run,[128] equivalent to $812.1 million adjusted for inflation in 2018.[129]

Internationally, the film grossed $455.8 million during its initial run, for a worldwide total of $763.5 million.[110] It had record openings in Sweden and Denmark.[130]

Re-releases[edit]

IMAX and large-format[edit]

The film was re-issued on December 25, 2002, for IMAX and large-format theaters. Don Hahn explained that eight years after The Lion King had its original release, «there was a whole new generation of kids who haven’t really seen it, particularly on the big screen.» Given the film had already been digitally archived during production, the restoration process was easier, while also providing many scenes with enhancements that covered up original deficiencies.[69][131] An enhanced sound mix was also provided to, as Hahn explained, «make the audience feel like they’re in the middle of the movie.»[69] On its first weekend, The Lion King made $2.7 million from 66 locations, a $27,664 per theater average. This run ended with $15.7 million on May 30, 2003.[132]

3D conversion[edit]

In 2011, The Lion King was converted to 3D for a two-week limited theatrical re-issue and subsequent 3D Blu-ray release.[104][133] The film opened at the number one spot on Friday, September 16, 2011, with $8.9 million[134] and finished the weekend with $30.2 million, ranking number one at the box office. This made The Lion King the first re-issue release to earn the number-one slot at the American weekend box office since the re-issue of Return of the Jedi (1983) in March 1997.[114] The film also achieved the fourth-highest September opening weekend of all time.[135] It held off very well on its second weekend, again earning first place at the box office with a 27 percent decline to $21.9 million.[136] Most box-office observers had expected the film to fall about 50 percent in its second weekend and were also expecting Moneyball (2011) to be at first place.[137]

After its initial box-office success, many theaters decided to continue to show the film for more than two weeks, even though its 3D Blu-ray release was scheduled for two-and-a-half weeks after its theatrical release.[136] In North America, the 3D re-release ended its run in theaters on January 12, 2012, with a gross of $94.2 million. Outside North America, it earned $83.4 million.[138] The successful 3D re-release of The Lion King made Disney and Pixar plan 3D theatrical re-releases of Beauty and the Beast, Finding Nemo (2003), Monsters, Inc. (2001), and The Little Mermaid (1989) during 2012 and 2013.[139] However, none of the re-releases of the first three films achieved the enormous success of The Lion King 3D and the theatrical re-release of The Little Mermaid was ultimately cancelled.[140] In 2012, Ray Subers of Box Office Mojo wrote that the reason why the 3D version of The Lion King succeeded was because, «the notion of a 3D re-release was still fresh and exciting, and The Lion King (3D) felt timely given the movie’s imminent Blu-ray release. Audiences have been hit with three 3D re-releases in the year since, meaning the novelty value has definitely worn off.»[141]

Critical response [edit]

On Rotten Tomatoes, the film has an approval rating of 93% with an average score of 8.4/10, based on 135 reviews. The website’s critical consensus reads, «Emotionally stirring, richly drawn, and beautifully animated, The Lion King stands tall within Disney’s pantheon of classic family films.»[142] It also ranked 56th on their «Top 100 Animation Movies».[143] At Metacritic, which uses a weighted average, the film received a score of 88 out of 100 based on 30 critics, indicating «universal acclaim».[144] Audiences polled by CinemaScore gave the film a rare «A+» grade on an A+ to F scale.[145]

Roger Ebert of the Chicago Sun-Times gave the film three-and-a-half stars out of a possible four and called it «a superbly drawn animated feature». He further wrote in his print review, «The saga of Simba, which in its deeply buried origins owes something to Greek tragedy and certainly to Hamlet, is a learning experience as well as an entertainment.»[4] On the television program Siskel & Ebert, the film was praised but received a mixed reaction when compared to the previous Disney films. Ebert and his partner Gene Siskel both gave the film a «Thumbs Up», but Siskel said that it was not as good as Beauty and the Beast and that it was «a good film, not a great one».[146] Hal Hinson of The Washington Post called it «an impressive, almost daunting achievement» and felt that the film was «spectacular in a manner that has nearly become commonplace with Disney’s feature-length animations», but was less enthusiastic toward the end of his review saying, «Shakespearean in tone, epic in scope, it seems more appropriate for grown-ups than for kids. If truth be told, even for adults it is downright strange.»[147]

Owen Gleiberman of Entertainment Weekly praised the film, writing that it «has the resonance to stand not just as a terrific cartoon but as an emotionally pungent movie».[148]

Rolling Stone film critic Peter Travers praised the film and felt that it was «a hugely entertaining blend of music, fun, and eye-popping thrills, though it doesn’t lack for heart».[149] James Berardinelli from Reelviews.net praised the film saying, «With each new animated release, Disney seems to be expanding its already-broad horizons a little more. The Lion King is the most mature (in more than one sense) of these films, and there clearly has been a conscious effort to please adults as much as children. Happily, for those of us who generally stay far away from ‘cartoons’, they have succeeded.»[150]

Some reviewers still had problems with the film’s narrative. The staff of TV Guide wrote that while The Lion King was technically proficient and entertaining, it «offers a less memorable song score than did the previous hits, and a hasty, unsatisfying dramatic resolution.»[151] The New Yorker‘s Terrence Rafferty considered that despite the good animation, the story felt like «manipulat[ing] our responses at will», as «Between traumas, the movie serves up soothingly banal musical numbers and silly, rambunctious comedy».[152]

Accolades[edit]

Other honors[edit]

In 2008, The Lion King was ranked as the 319th greatest film ever made by Empire magazine,[173] and in June 2011, TIME named it one of «The 25 All-TIME Best Animated Films».[174] In June 2008, the American Film Institute listed The Lion King as the fourth best film in the animation genre in its AFI’s 10 Top 10 list,[175] having previously put «Hakuna Matata» as 99th on its AFI’s 100 Years…100 Songs ranking.[176]

In 2016, the film was selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry by the Library of Congress as being «culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant».

Year-end lists[edit]

- 2nd – Douglas Armstrong, The Milwaukee Journal[177]

- 5th – Sandi Davis, The Oklahoman[178]

- 5th – Todd Anthony, Miami New Times[179]

- 6th – Stephen Hunter, The Baltimore Sun[180]

- 6th – Christopher Sheid, The Munster Times[181]

- 7th – Joan Vadeboncoeur, Syracuse Herald American[182]

- 7th – Dan Craft, The Pantagraph[183]

- 8th – Steve Persall, St. Petersburg Times[184]

- 8th – Desson Howe, The Washington Post[185]

- 10th – Mack Bates, The Milwaukee Journal[186]

- 10th – David Elliott, The San Diego Union-Tribune[187]

- Top 7 (not ranked) – Duane Dudek, Milwaukee Sentinel[188]

- Top 9 (not ranked) – Dan Webster, The Spokesman-Review[189]

- Top 10 (listed alphabetically, not ranked) – Matt Zoller Seitz, Dallas Observer[190]

- Top 10 (listed alphabetically, not ranked) – William Arnold, Seattle Post-Intelligencer[191]

- Top 10 (listed alphabetically, not ranked) – Mike Mayo, The Roanoke Times[192]

- Top 10 (not ranked) – Bob Carlton, The Birmingham News[193]

- «The second 10» (not ranked) – Sean P. Means, The Salt Lake Tribune[194]

- Honorable mention – Michael MacCambridge, Austin American-Statesman[195]

- Honorable mention – Dennis King, Tulsa World[196]

- Honorable mention – Glenn Lovell, San Jose Mercury News[197]

- Honorable mention – John Hurley, Staten Island Advance[198]

- Honorable mention – Jeff Simon, The Buffalo News[199]

Controversies[edit]

Kimba the White Lion[edit]

Screenshot from an early presentation reel of The Lion King that shows a white lion cub and a butterfly.

Certain elements of the film were thought to bear a resemblance to Osamu Tezuka’s 1960s Japanese anime television series, Jungle Emperor (known as Kimba the White Lion in the United States), with some similarities between a number of characters and various individual scenes. The 1994 release of The Lion King drew a protest in Japan, where Kimba and its creator Osamu Tezuka are cultural icons. 488 Japanese cartoonists and animators, led by manga author Machiko Satonaka, signed a petition accusing Disney of plagiarism and demanding that they give due credit to Tezuka.[200][201] Matthew Broderick believed initially that he was, in fact, working on an American version of Kimba since he was familiar with the Japanese original.[202]

The Lion King director Roger Allers claimed complete unfamiliarity with the series until the movie was nearly completed, and did not remember it being ever mentioned during development.[26] Madhavi Sunder has suggested that Allers might have seen the 1989 remake of Kimba on prime time television while living in Tokyo. However, while Allers did indeed move to Tokyo in 1983 in order to work on Little Nemo: Adventures in Slumberland (1989), he moved back to the United States in 1985, four years before the 1989 remake of Kimba began airing.[9][203] Co-director Rob Minkoff also stated that he was unfamiliar with it.[204][205] Minkoff also observed that whenever a story is based in Africa, it is «not unusual to have characters like a baboon, a bird, or hyenas.»[204]

Takayuki Matsutani, the president of Tezuka Productions which created Kimba the White Lion, said in 1994 that «quite a few staff of our company saw a preview of The Lion King, discussed this subject and came to the conclusion that you cannot avoid having these similarities as long as you use animals as characters and try to draw images out of them».[206] Yoshihiro Shimizu of Tezuka Productions has refuted rumors that the studio was paid hush money by Disney and stated that they have no interest in suing Disney, explaining that «we think it’s a totally different story». Shimizu further explained that they rejected urges from some American lawyers to sue because «we’re a small, weak company… Disney’s lawyers are among the top twenty in the world!»[207] Tezuka’s family and Tezuka Productions never pursued litigation.[208]

Fred Ladd, who was involved early on with importing Kimba and other Japanese anime into America for NBC, expressed incredulity that Disney’s people could remain ignorant.[209][205] Ladd stated there was at least one animator remembered by his colleagues as being an avid Kimba fan and being quite vociferous about Disney’s conduct during production.[209] Animators Tom Sito and Mark Kausler have both stated that they had watched Kimba as children in the 1960s. However, Sito maintains there was «absolutely no inspiration» from Kimba during the production of The Lion King, and Kausler emphasized Disney’s own Bambi as being their model during development.[210][206]

The controversy surrounding Kimba and The Lion King was parodied in The Simpsons episode «‘Round Springfield», where Mufasa appears through the clouds and says, «You must avenge my death, Kimba… I mean, Simba.»[211]

Other controversies[edit]

Protests were raised against one scene where it appears as if the word «SEX» might have been embedded into the dust flying in the sky when Simba flops down,[212] which conservative activist Donald Wildmon asserted was a subliminal message intended to promote sexual promiscuity. Animator Tom Sito has stated that the letters spell «SFX» (a common abbreviation for «special effects»), not with an «E» instead of the «F», and were intended as an innocent «signature» created by the effects animation team.[213]

Hyena biologists protested against the animal’s portrayal, though the complaints may have been somewhat tongue-in-cheek. One hyena researcher, who had organized the animators’ visit to the University of California, Berkeley, Field Station for the Study of Behavior, Ecology, and Reproduction, where they would observe and sketch captive hyenas,[214] listed «boycott The Lion King» in an article listing ways to help preserve hyenas in the wild, and later «joke[d] that The Lion King set back hyena conservation efforts.»[215][216] Even so, the film was also credited with «spark[ing] an interest» in hyenas at the Berkeley center.[216]

The film has been criticized for race and class issues, with the hyenas seen as reflecting negative stereotypes of black and Latino ethnic communities.[217][218][219]

Legacy[edit]

Sequels and spin-offs[edit]

The first Lion King–related animated project was the spin-off television series, The Lion King’s Timon & Pumbaa, which centers on the characters of Timon and Pumbaa, as they have their own (mis)adventures both within’ and outside of the Serengeti. the show ran for three seasons and 85 episodes between 1995 and 1999. Ernie Sabella continued to voice Pumbaa, while Timon was voiced by Quinton Flynn and Kevin Schon in addition to Nathan Lane.[220] One of the show’s music video segments «Stand By Me», featuring Timon singing the eponymous song, was later edited into an animated short which was released in 1995, accompanying the theatrical release of Tom and Huck (1995).

Disney released two direct-to-video films related to The Lion King. The first was sequel The Lion King II: Simba’s Pride, released in 1998 on VHS. The film centers around Simba and Nala’s daughter, Kiara, who falls in love with Kovu, a male lion who was raised in a pride of Scar’s followers, the Outsiders.[221] The Lion King 1½, another direct-to-video Lion King film, saw its release in 2004. It is a prequel in showing how Timon and Pumbaa met each other, and also a parallel in that it also depicts what the characters were retconned to have done during the events of the original movie.[222]

In June 2014, it was announced that a new TV series based on the film would be released called The Lion Guard, featuring Kion, the second-born cub of Simba and Nala. The Lion Guard is a sequel to The Lion King and takes place during the time-gap within The Lion King II: Simba’s Pride,[223] with the last 2 episodes of Season 3 taking place after the events of that film. It was first broadcast on Disney Channel as a television film titled The Lion Guard: Return of the Roar in November 2015 before airing as a series on Disney Junior in January 2016.[224][225]

CGI remake[edit]

In September 2016, following the critical and financial success of The Jungle Book, Walt Disney Pictures announced that they were developing a CGI remake of The Lion King by the same name, with Jon Favreau directing.[226] The following month, Jeff Nathanson was hired to write the script for the film.[227] Favreau originally planned to shoot it back-to-back with the sequel to The Jungle Book.[226][228] However, it was reported in early 2017 that the latter film was put on hold in order for Favreau to instead focus mainly on The Lion King.[229] In February 2017, Favreau announced that Donald Glover had been cast as Simba and that James Earl Jones would be reprising the role of Mufasa.[230] The following month, it was reported that Beyoncé was Favreau’s top choice to voice Nala, but she had not accepted the role yet due to a pregnancy.[231] In April 2017, Billy Eichner and Seth Rogen joined the film as Timon and Pumbaa, respectively.[232] Two months later, John Oliver was cast as Zazu.[233] At the end of July 2017, Beyoncé had reportedly entered final negotiations to play Nala and contribute a new soundtrack.[234] The following month, Chiwetel Ejiofor entered talks to play Scar.[235] Later on, Alfre Woodard and John Kani joined the film as Sarabi and Rafiki, respectively.[236][237] On November 1, 2017, Beyoncé and Chiwetel Ejiofor were officially confirmed to voice Nala and Scar, with Eric André, Florence Kasumba, Keegan-Michael Key, JD McCrary, and Shahadi Wright Joseph joining the cast as the voices of Azizi, Shenzi, and Kamari, young Simba, and young Nala, respectively, while Hans Zimmer would return to score the film’s music.[238][239][240][241][242] On November 28, 2017, it was reported that Elton John had signed onto the project to rework his musical compositions from the original film.[243]

Production for the film began in May 2017.[244] It was released on July 19, 2019.[245]

Black Is King[edit]

In June 2020, Parkwood Entertainment and Disney announced that a film titled Black Is King would be released on July 31, 2020, on Disney+. The live-action film is inspired by The Lion King (2019) and serves as a visual album for the tie-in album The Lion King: The Gift, which was curated by Beyoncé for the film.[246] Directed, written and executive produced by Beyoncé, Black Is King is described as reimagining «the lessons of The Lion King for today’s young kings and queens in search of their own crowns».[247] The film chronicles the story of a young African king who undergoes a «transcendent journey through betrayal, love and self-identity» to reclaim his throne, utilizing the guidance of his ancestors and childhood love, with the story being told through the voices of present-day Black people.[248] The cast includes Lupita Nyong’o, Naomi Campbell, Jay-Z, Kelly Rowland, Pharrell Williams, Tina Knowles-Lawson, Aweng Ade-Chuol, and Adut Akech.[247]

Mufasa: The Lion King[edit]

On September 29, 2020, Deadline Hollywood reported that a follow-up film was in development with Barry Jenkins attached to direct.[249] While The Hollywood Reporter said the film would be a prequel about Mufasa during his formative years, Deadline said it would be a sequel centering on both Mufasa’s origins and the events after the first film, similar to The Godfather Part II. Jeff Nathanson, the screenwriter for the remake, has reportedly finished a draft.[250][251] In August 2021, it was reported that Aaron Pierre and Kelvin Harrison Jr. had been cast as Mufasa and Scar respectively.[252] The film will not be a remake of The Lion King II: Simba’s Pride, the 1998 direct-to-video sequel to the original animated film.[253] In September 2022 at the D23 Expo, it was announced that the film will be titled Mufasa: The Lion King and that it will follow the titular character’s origin story. Seth Rogen, Billy Eichner, and John Kani will reprise their roles as Pumbaa, Timon, and Rafiki, respectively. The film is scheduled to release on July 5, 2024.[254][255]

Video games[edit]

Along with the film release, three different video games based on The Lion King were released by Virgin Interactive in December 1994. The main title was developed by Westwood Studios, and published for PC and Amiga computers and the consoles SNES and Sega Mega Drive/Genesis. Dark Technologies created the Game Boy version, while Syrox Developments handled the Master System and Game Gear version.[256] The film and sequel Simba’s Pride later inspired another game, Torus Games’ The Lion King: Simba’s Mighty Adventure (2000) for the Game Boy Color and PlayStation.[257] Timon and Pumbaa also appeared in Timon & Pumbaa’s Jungle Games, a 1995 PC game collection of puzzle games by 7th Level, later ported to the SNES by Tiertex.[258]

The Square Enix series Kingdom Hearts features Simba as a recurring summon,[259][260] as well as a playable in the Lion King world, known as Pride Lands, in Kingdom Hearts II. There the plotline is loosely related to the later part of the original film, with all of the main characters except Zazu and Sarabi.[261] The Lion King also provides one of the worlds featured in the 2011 action-adventure game Disney Universe,[262] and Simba was featured in the Nintendo DS title Disney Friends (2008).[263] The video game Disney Magic Kingdoms includes some characters of the film and some attractions based on locations of the film as content to unlock for a limited time.[264][265]

Stage adaptations[edit]

Walt Disney Theatrical produced a musical stage adaptation of the same name, which premiered in Minneapolis, Minnesota in July 1997, and later opened on Broadway in October 1997 at the New Amsterdam Theatre. The Lion King musical was directed by Julie Taymor[266] and featured songs from both the movie and Rhythm of the Pride Lands, along with three new compositions by Elton John and Tim Rice. Mark Mancina did the musical arrangements and new orchestral tracks.[267] To celebrate the African culture background the story is based on, there are six indigenous African languages sung and spoken throughout the show: Swahili, Zulu, Xhosa, Sotho, Tswana, Congolese.[268] The musical became one of the most successful in Broadway history, winning six Tony Awards including Best Musical, and despite moving to the Minskoff Theatre in 2006, is still running to this day in New York, becoming the third longest-running show and highest grossing Broadway production in history. The show’s financial success led to adaptations all over the world.[24][269][270]

The Lion King inspired two attractions retelling the story of the film at Walt Disney Parks and Resorts. The first, «The Legend of the Lion King», featured a recreation of the film through life-size puppets of its characters, and ran from 1994 to 2002 at Magic Kingdom in Walt Disney World.[271] Another that is still running is the live-action 30-minute musical revue of the movie, «Festival of the Lion King», which incorporates the musical numbers into gymnastic routines with live actors, along with animatronic puppets of Simba and Pumbaa and a costumed actor as Timon. The attraction opened in April 1998 at Disney World’s Animal Kingdom,[272] and in September 2005 in Hong Kong Disneyland’s Adventureland.[273] A similar version under the name «The Legend of the Lion King» was featured in Disneyland Paris from 2004 to 2009.[274][275]

See also[edit]

- Cultural depictions of lions

- Atlantis: The Lost Empire and Nadia: The Secret of Blue Water controversy, a similar plagiarism controversy

- The Thief and the Cobbler

References[edit]

- ^ «The Lion King (U)». British Board of Film Classification. Archived from the original on September 21, 2013. Retrieved July 21, 2013.

- ^ a b c d «The Lion King (1994)«. Box Office Mojo. IMDb. Archived from the original on October 23, 2020. Retrieved January 23, 2021.

- ^ Brevert, Brad (May 29, 2016). «‘X-Men’ & ‘Alice’ Lead Soft Memorial Day Weekend; Disney Tops $4 Billion Worldwide». Box Office Mojo. Retrieved January 28, 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ a b Ebert, Roger (June 24, 1994). «The Lion King review». Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on July 8, 2014. Retrieved April 14, 2014 – via rogerebert.com.

Basically what we have here is a drama, with comedy occasionally lifting the mood.

- ^ a b Natale, Richard (December 30, 1994). «The Movie Year: Hollywood Loses Its Middle Class». Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on January 23, 2022.

- ^ «With «20,000 Leagues,» the National Film Registry Reaches 700″ (Press release). National Film Registry. December 23, 2016. Archived from the original on November 26, 2020. Retrieved November 23, 2020.

- ^ Fallon, Kevin (June 24, 2014). «‘The Lion King’ Turns 20: Every Crazy, Weird Fact About the Disney Classic». The Daily Beast. Retrieved October 31, 2021.

- ^ Mendoza, Jessie (December 22, 2019). «The Lion King (1994 movie)». Startattle. Retrieved October 31, 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s «The Lion King: Production Notes» (Press release). Walt Disney Pictures. May 25, 1994. Archived from the original on October 26, 2008. Retrieved August 5, 2008 – via LionKing.org.

- ^ Lawson, Tim; Persons, Alisa (December 9, 2004). The Magic Behind the Voices: A Who’s Who of Cartoon Voice Actors. ISBN 978-1-57806-696-4. Archived from the original on June 27, 2014. Retrieved March 13, 2016.

- ^ a b Koenig 1997, p. 227.

- ^ a b Neuwirth 2003, p. 13.

- ^ Chandler 2018, p. 330.

- ^ Geirland & Keidar 1999, p. 49.

- ^ Stewart 2005, p. 108.

- ^ a b c d e Don Hahn (2011). The Lion King: A Memoir (Blu-ray). The Lion King: Diamond Edition: Walt Disney Home Entertainment.

- ^ a b c d The Pride of the King (Blu-ray). The Lion King: Diamond Edition: Walt Disney Home Entertainment. 2011.

- ^ «The Origins of ‘The Lion King’«. James Cummins Book Seller. Archived from the original on April 13, 2014. Retrieved October 22, 2011.

- ^ Chandler 2018, p. 335.

- ^ a b Chandler 2018, pp. 338–339.

- ^ a b Neuwirth 2003, p. 14.

- ^ Neuwirth 2003, pp. 107–108.

- ^ a b c «The Lion King: The Landmark Musical Event» (PDF) (Press release). Walt Disney Company. 2013. p. 7. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 22, 2014. Retrieved February 14, 2014.

- ^ a b c d Daly, Steve (July 8, 1994). «Mane Attraction». Entertainment Weekly. No. 230. Archived from the original on July 16, 2014. Retrieved September 30, 2020.

- ^ a b Fiamma, Andrea (December 12, 2014). «Intervista a Roger Allers, il regista de Il Re Leone». Fumettologica (Interview). Archived from the original on February 1, 2015. Retrieved March 30, 2015.

The whole time I worked on The Lion King the name of that show never came up. At least I never heard it. I had never seen the show and really only became aware of it as Lion King was being completed, and someone showed me images of it. I worked with George Scribner and Linda Woolverton to develop the story in the early days but then left to help out on Aladdin. If one of them were familiar with Kimba they didn’t say. Of course, it’s possible… Many story ideas developed and changed along the way, always just to make our story stronger. I could certainly understand Kimba‘s creators feeling angry if they felt we had stolen ideas from them. If I had been inspired by Kimba I would certainly acknowledge my inspiration. All I can offer is my respect to those artists and say that their creation has its loyal admirers and its assured place in animation history.

- ^ Kroyer & Sito 2019, pp. 267–268.

- ^ a b Neuwirth 2003, p. 147.

- ^ Finch 1994, pp. 168–169.

- ^ Neuwirth 2003, p. 108.

- ^ Finch 1994, p. 166.

- ^ Finch 1994, pp. 165–193.

- ^ Kroyer & Sito 2019, p. 268.

- ^ a b c Story Origins (DVD). The Lion King: Platinum Edition: Walt Disney Home Entertainment. 2003.

- ^ a b «The Music of The Lion King: A 20th Anniversary Conversation with Rob Minkoff and Mark Mancina». Projector & Orchestra. September 17, 2014. Archived from the original on October 16, 2014. Retrieved October 12, 2022.

- ^ Neuwirth 2003, p. 149.

- ^ KyleKallgrenBHH (September 10, 2015). The Lion King, or The History of King Simba I — Summer of Shakespeare. YouTube. Retrieved September 2, 2022 – via YouTube.

- ^ Finch 1994, p. 171.

- ^ Finch 1994, p. 172.

- ^ Neuwirth 2003, p. 176.

- ^ a b c The Making of The Lion King (Laserdisc). The Lion King laserdisc: Walt Disney Home Entertainment. 1995.

- ^ a b Redmond, Aiden (September 15, 2011). «Jeremy Irons and James Earl Jones on ‘The Lion King 3D’ and Keeping It Together When Mufasa Dies». Moviefone. Archived from the original on March 6, 2014. Retrieved April 5, 2014.

- ^ a b King, Susan (September 15, 2011). «A ‘Lion’s’ tale». Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on October 24, 2011. Retrieved October 24, 2011.

- ^ Mortimer, Bob (2021). And Away. Gallery Books. pp. Chapter 25. ISBN 978-1398505292.

- ^ Hayes, A. Cydney (October 28, 2018). «Why Rowan Atkinson originally didn’t want to be the voice of Zazu in The Lion King«. Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on October 28, 2018. Retrieved July 11, 2022.

- ^ Kehr, Dave (December 27, 2002). «The Lion Evolves». The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 10, 2014. Retrieved April 5, 2014.

- ^ Hischak, Thomas S (2011). Disney Voice Actors: A Biographical Dictionary. United States: McFarland. p. 106. ISBN 9780786486946 – via Google Books.

- ^ Knolle, Sharon (June 14, 2014). «‘The Lion King’: 20 Things You Didn’t Know About the Disney Classic». Moviefone. Archived from the original on June 17, 2014. Retrieved July 11, 2014.

- ^ Willman, Chris (May 15, 1994). «SUMMER SNEAKS ’94: You Can’t Hide His Lion Eyes». Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on April 7, 2014. Retrieved April 5, 2014.

- ^ Neuwirth 2003, p. 107.

- ^ Ghez, Didier, ed. (2010). «Burny Mattinson». Walt’s People—Volume 9. Xlibris Corporation. pp. 463–464. ISBN 978-1-4500-8746-9.[self-published source]

- ^ Brew, Simon (November 8, 2019). «How 1994’s The Lion King had to be completed in people’s spare rooms». filmstories.co.uk.

- ^ Finch 1994, p. 173.

- ^ «FilMiami’s Shining Star: Ron Magill». FilmMiami. Miami-Dade County. Archived from the original on May 25, 2015. Retrieved May 24, 2015.

- ^ Finch 1994, p. 170.

- ^ Bacher, Hans P. (2008). Dream worlds: production design for animation. Focal Press. p. 66. ISBN 978-0-240-52093-3.

- ^ The Lion King: Platinum Edition (Disc 2), Computer Animation (DVD). Walt Disney Home Entertainment. 2003.

- ^ White, Timothy (October 4, 1997). «Elton John: The Billboard Interview». Billboard. pp. 95–96. Archived from the original on September 28, 2014. Retrieved March 13, 2016 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b The Lion King: Platinum Edition (Disc 1), Music: African Influence (DVD). Walt Disney Home Entertainment. 2003.

- ^ The Making of The Morning Report (DVD). The Lion King: Platinum Edition (Disc 1): Walt Disney Home Entertainment. 2003.

{{cite AV media}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ^ Finch 1994, pp. 192–193.

- ^ The Lion King (Booklet). Hans Zimmer, Elton John, Tim Rice. Walt Disney Records. 1994. 60858-7.

{{cite AV media notes}}: CS1 maint: others in cite AV media (notes) (link) - ^ «Year-end 1994 Billboard 200». Billboard. Archived from the original on June 1, 2008. Retrieved August 5, 2008.

- ^ Grisham, Lori (May 7, 2014). «Walt Disney Records to release legacy collection». USA Today. Archived from the original on September 14, 2015. Retrieved June 25, 2014.

- ^ «Rhythm of the Pride Lands: The Musical Journey Continues …» Billboard. January 5, 1995. Archived from the original on July 4, 2014. Retrieved March 13, 2016.

- ^ «Disney settles Lion song dispute». BBC News. February 16, 2006. Archived from the original on February 22, 2014. Retrieved August 12, 2008.

- ^ a b Brew, Simon (November 3, 2011). «Don Hahn interview: The Lion King, Disney, Pixar, Frankenweenie and the future of animation». Den of Geek (Dennis Publishing). Archived from the original on February 22, 2014. Retrieved April 5, 2014.

- ^ Welkos, Robert W. (November 29, 1993). «Will ‘Lion King’ Be Disney’s Next ‘Beast’?». Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on March 4, 2014. Retrieved April 5, 2014.

- ^ a b c Kallay, William (December 2002). «The Lion King: The IMAX Experience». In 70mm. Archived from the original on April 12, 2014. Retrieved March 12, 2009.

- ^ Hofmeister, Sallie (July 12, 1994). «In the Realm of Marketing, ‘The Lion King’ Rules». The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 14, 2013. Retrieved April 5, 2014.

- ^ Tyler Eastman, Susan (2000). Research in media promotion. Routledge. p. 244. ISBN 978-0-8058-3382-9.

- ^ Olson, Scott Robert (1999). Hollywood planet: global media and the competitive advantage of narrative transparency. Taylor & Francis. p. 216. ISBN 978-0-8058-3230-3.

- ^ Broeske, Pat H. (June 23, 1995). «Playing for Keeps». Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on February 24, 2015. Retrieved April 5, 2014.

- ^ Bryman, Alan (2004). The Disneyization of Society. Sage. p. 86. ISBN 978-0-7619-6765-1.

- ^ Eller, Claudia (April 7, 1994). «Summer Movie Hype Coming In Like a ‘Lion’«. Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on March 5, 2016. Retrieved April 16, 2020.

- ^ «Mane Event». Variety. June 20, 1994. p. 1.

- ^ Fantel, Hans (June 12, 1994). «Technology; Cinema Sound Gets a Digital Life». The New York Times. Archived from the original on March 9, 2014. Retrieved April 5, 2014.

- ^ «Nala». CHARGUIGOU (in French). Archived from the original on July 25, 2019. Retrieved December 2, 2019.

- ^ «Inkosi Ubhubesi / The Lion King Zulu Voice Cast». WILLDUBGURU. Archived from the original on October 14, 2019. Retrieved May 22, 2020.

- ^ «‘Moana’ to be First Disney Film Translated Into Tahitian Language». Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on July 20, 2019. Retrieved December 2, 2019.

- ^ «Moana in Māori hits the big screen». RNZ. September 11, 2017. Archived from the original on July 20, 2019. Retrieved December 2, 2019.

- ^ «Disney’s Moana to make World Premiere in ‘Ōlelo Hawai’i at Ko Olina’s World Oceans Day, June 10». Ko Olina. Archived from the original on February 24, 2019. Retrieved December 2, 2019.

- ^ Milligan, Mercedes (July 19, 2019). «‘Frozen 2’ Will Get Sámi Language Version». Animation Magazine. Archived from the original on July 20, 2019. Retrieved December 2, 2019.

- ^ Idivuoma, Mariela (November 20, 2019). «Dette er de samiske Disney-stjernene». NRK. Archived from the original on January 18, 2020. Retrieved December 2, 2019.

- ^ a b Kohere, Reweti (June 23, 2022). «How The Lion King Reo Māori did what no other version has done before». The Spinoff. Retrieved July 9, 2022.

- ^ Oddo, Marco Vito (October 6, 2022). «‘Lion King,’ ‘Moana,’ and ‘Bambi’ Now Have Indigenous Language Dubs on Disney+ [Exclusive]». Collider. Retrieved October 12, 2022.

- ^ McConnell, Glenn (October 28, 2021). «Tainui royalty and Ngāti Kahungunu jokesters wanted for Māori Lion King». Stuff.

- ^ «Lion King Reo Māori premiere: ‘A dream come true’«. Radio New Zealand. June 22, 2022. Retrieved June 22, 2022.

- ^ Taylor, Piripi (October 28, 2021). «The hunt for Disney’s The Lion King reo Māori cast begins». Teaomaori.news. Retrieved July 9, 2022.

- ^ Brown, Laura (March 11, 1995). «Growling at ‘The Lion King’ Video». Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on December 6, 2021. Retrieved December 6, 2021.

- ^ a b «The Lion King home video selling figures». ComingSoon.Net. October 9, 2003. Archived from the original on February 22, 2005. Retrieved July 7, 2006.

- ^ Susman, Gary (October 13, 2003). ««Lion King» sets new records with DVD release». Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on April 11, 2015. Retrieved August 16, 2008.

- ^ a b «TLK on Home Video». Lionking.org. Archived from the original on October 10, 2006. Retrieved September 24, 2006.

- ^ «Charts – TOP VENTES VHS». JP’s Box Office. Archived from the original on November 24, 2018. Retrieved November 24, 2018.

- ^ Grover, Ronald (February 16, 1998). «The Entertainment Glut». Bloomberg Businessweek. Bloomberg L.P. Archived from the original on October 12, 2017. Retrieved May 1, 2017.

- ^ «Standard & Poor’s Industry Surveys». Standard & Poor’s Industry Surveys. Standard & Poor’s Corporation. 164 (2): 29. 1996. Archived from the original on August 20, 2020. Retrieved June 23, 2019 – via Google Books.

The top-selling video of 1995 was Disney’s The Lion King, which sold more than 30 million copies in North America after its release in March of that year. Toward the end of 1995, another 23 million copies of the animated musical were shipped for sale in international markets.

- ^ Red, Isah Vasquez (March 10, 1995). «Scary and scarred». Manila Standard. Kamahalan Publishing Corp. p. 22. Archived from the original on April 16, 2021. Retrieved April 16, 2021.

- ^ «Best-Selling Video». The Guinness Book of Records 1999. Guinness World Records. 1998. p. 215. ISBN 978-0-85112-070-6.

- ^ a b «The Lion King: Platinum Edition DVD Review (Page 2) which shows the differences between the film presented on the DVD and the original theatrical cut». UltimateDisney.com. Archived from the original on July 18, 2011. Retrieved January 24, 2009.

- ^ «The Lion King Special Edition». IGN. April 16, 2003. Archived from the original on March 22, 2013. Retrieved September 18, 2006.

- ^ «The Lion King: Platinum Edition (1994) — DVD Movie Guide».

- ^ «Out of Print Disney DVDs». UltimateDisney.com. Archived from the original on September 8, 2014. Retrieved September 24, 2006.

- ^ «Charts – TOP VENTES DVD». JP’s Box Office. Archived from the original on November 25, 2018. Retrieved November 24, 2018.

- ^ a b c d e «Audiences to Experience Disney’s «The Lion King» Like Never Before». PR News Wire. May 26, 2011. Archived from the original on May 30, 2011. Retrieved May 26, 2011.

- ^ a b «Exclusive: Lion King 3D Blu-ray Details». IGN. May 25, 2011. Archived from the original on October 17, 2014. Retrieved May 26, 2011.

- ^ Latchem, John (October 18, 2011). «‘Lion King,’ ‘Fast Five’ Propel Blu-ray to Record-breaking Week». Home Media Magazine. Archived from the original on February 22, 2014. Retrieved December 24, 2011.

- ^ C.S.Strowbridge (March 1, 2012). «Blu-ray Sales: Vamp Defeat Tramp». The Numbers. Archived from the original on June 17, 2015. Retrieved March 1, 2012.

- ^ «John [sic] Favreau Shares First Look at Live-Action LION KING at D23 Expo». Broadway World. July 17, 2017. Archived from the original on July 20, 2017. Retrieved July 17, 2017.

- ^ «The Lion King – 4K Ultra HD Blu-ray Ultra HD Review | High Def Digest». ultrahd.highdefdigest.com. Archived from the original on November 14, 2018. Retrieved January 22, 2019.

- ^ a b «The Lion King (1994): Original Release». Box Office Mojo. Retrieved January 8, 2023.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Hooton, Christopher (January 14, 2014). «Frozen becomes highest-grossing Disney animated film of all time». The Independent. Archived from the original on April 7, 2014. Retrieved April 5, 2014.

- ^ «1994 WORLDWIDE GROSSES». Archived from the original on September 28, 2011. Retrieved September 26, 2011.

- ^ ««You Can’t Actually Blow Up the White House»: An Oral History of ‘Independence Day’«. The Hollywood Reporter. July 2, 2021.

- ^ a b Subers, Ray (September 19, 2011). «Weekend Report: ‘Lion King’ Regains Box Office Crown». Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on April 3, 2014. Retrieved April 5, 2014.

- ^ Gray, Brandon (September 16, 2011). «Forecast: ‘Lion King’ to Roar Again». Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on April 4, 2014. Retrieved April 5, 2014.

- ^ «Top Grossing G Rated at Box Office Mojo». Box Office Mojo. August 18, 2019. Archived from the original on April 4, 2019. Retrieved September 1, 2019.

- ^ Natale, Richard (June 20, 1994). «‘Wolf,’ ‘Lion King’ Grab the Movie-Goers». Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on March 4, 2014. Retrieved April 5, 2014.

- ^ «Top Weekend Theater Averages». Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on September 19, 2011. Retrieved September 26, 2011.

- ^ «All-Time Opening Weekends: 50 Screens or Less». Daily Variety. September 20, 1994. p. 24.

- ^ «Domestic Box Office». Variety. June 27, 1994. p. 10.

- ^ «‘Lion King’ rules nation’s box office». United Press International. June 27, 1994. Archived from the original on February 13, 2022. Retrieved February 13, 2022.

- ^ «‘Lion King’ Opening with Box Office Roar». Chicago Tribune. June 28, 1994. Archived from the original on January 25, 2022.

- ^ Lyman, Rick (November 29, 1999). «Those Toys Are Leaders In Box-Office Stampede». The New York Times. Archived from the original on March 19, 2022. Retrieved March 25, 2022.

- ^ «Powerhouses Fuel Sales at Box Office». Los Angeles Times. July 18, 1994. Archived from the original on July 26, 2010. Retrieved October 24, 2019.

- ^ Hofmeister, Sally (August 13, 1994). «Disney to Put ‘Lion King’ Into Early Hibernation». The New York Times. Archived from the original on July 19, 2019. Retrieved July 18, 2019.