| Amazon River

Rio Amazonas |

|

|---|---|

Amazon River |

|

Amazon River and its drainage basin |

|

| Native name | Amazonas (Portuguese) |

| Location | |

| Country | Peru, Colombia, Brazil |

| City | Iquitos (Peru); Leticia (Colombia); Tabatinga (Brazil); Tefé (Brazil); Itacoatiara (Brazil) Parintins (Brazil); Óbidos (Brazil); Santarém (Brazil); Almeirim (Brazil); Macapá (Brazil); Manaus (Brazil) |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Source | Río Apurimac, Mismi Peak |

| • location | Arequipa Region, Peru |

| • coordinates | 15°31′04″S 71°41′37″W / 15.51778°S 71.69361°W |

| • elevation | 5,220 m (17,130 ft) |

| Mouth | Atlantic Ocean |

|

• location |

Brazil |

|

• coordinates |

0°42′28″N 50°5′22″W / 0.70778°N 50.08944°W[1] |

| Length | 6,500 km (4,000 mi)[n 1] |

| Basin size | 7,000,000 km2 (2,700,000 sq mi)[2] 6,743,000 km2 (2,603,000 sq mi)[5] |

| Width | |

| • minimum | 700 m (2,300 ft) (Upper Amazon); 1.5 km (0.93 mi) (Itacoatiara, Lower Amazon)[6] |

| • average | 3 km (1.9 mi) (Middle Amazon); 5 km (3.1 mi) (Lower Amazon)[6][7] |

| • maximum | 10 km (6.2 mi) to 14 km (8.7 mi) (Lower Amazon);[6][8] 340 km (210 mi) (estuary)[9] |

| Depth | |

| • average | 15 m (49 ft) to 45 m (148 ft) (Middle Amazon); 20 m (66 ft) to 50 m (160 ft) (Lower Amazon)[6] |

| • maximum | 150 m (490 ft) (Itacoatiara); 130 m (430 ft) (Óbidos)[6][7] |

| Discharge | |

| • location | Atlantic Ocean (near mouth) |

| • average | 215,000 m3/s (7,600,000 cu ft/s)–230,000 m3/s (8,100,000 cu ft/s)[10][11]

(Basin size: 5,956,000 km2 (2,300,000 sq mi)[12] 205,603.262 m3/s (7,260,810.7 cu ft/s)[13] (Basin size: 5,912,760.5 km2 (2,282,929.6 sq mi)[13] |

| • minimum | 180,000 m3/s (6,400,000 cu ft/s) |

| • maximum | 340,000 m3/s (12,000,000 cu ft/s) |

| Discharge | |

| • location | Amazon Delta, Amazon/Tocantins/Pará |

| • average | 230,000 m3/s (8,100,000 cu ft/s)[5] (Basin size: 6,743,000 km2 (2,603,000 sq mi)[5] to 7,000,000 km2 (2,700,000 sq mi)[2] |

| Discharge | |

| • location | Santarém |

| • average | 191,624.043 m3/s (6,767,139.2 cu ft/s)[13] |

| Discharge | |

| • location | Óbidos (800 km upstream of mouth — Basin size: 4,704,076 km2 (1,816,254 sq mi) |

| • average | 173,272.643 m3/s (6,119,065.6 cu ft/s)[13]

(Period of data: 1928-1996)176,177 m3/s (6,221,600 cu ft/s)[14] (Period of data: 01/01/1997-31/12/2015)178,193.9 m3/s (6,292,860 cu ft/s)[15] |

| • minimum | 75,602 m3/s (2,669,900 cu ft/s)[14] |

| • maximum | 306,317 m3/s (10,817,500 cu ft/s)[14] |

| Discharge | |

| • location | Manacapuru, Solimões (Basin size: 2,147,736 km2 (829,246 sq mi) |

| • average | (Period of data: 01/01/1997-31/12/2015) 105,720 m3/s (3,733,000 cu ft/s)[15] |

| Basin features | |

| Tributaries | |

| • left | Marañón, Nanay, Napo, Ampiyaçu, Japurá/Caquetá, Rio Negro/Guainía, Putumayo, Badajós, Manacapuru, Urubu, Uatumã, Nhamundá, Trombetas, Maicurú, Curuá, Paru, Jari |

| • right | Ucayali, Jandiatuba, Javary, Jutai, Juruá, Tefé, Coari, Purús, Madeira, Paraná do Ramos, Tapajós, Curuá-Una, Xingu, Pará, Tocantins, Acará, Guamá |

Topography of the Amazon River Basin

The Amazon River (, ; Spanish: Río Amazonas, Portuguese: Rio Amazonas) in South America is the largest river by discharge volume of water in the world, and the disputed longest river system in the world in comparison to the Nile.[2][16][n 2]

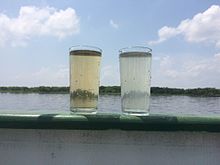

The headwaters of the Apurímac River on Nevado Mismi had been considered for nearly a century the Amazon basin’s most distant source, until a 2014 study found it to be the headwaters of the Mantaro River on the Cordillera Rumi Cruz in Peru.[21] The Mantaro and Apurímac rivers join, and with other tributaries form the Ucayali River, which in turn meets the Marañón River upstream of Iquitos, Peru, forming what countries other than Brazil consider to be the main stem of the Amazon. Brazilians call this section the Solimões River above its confluence with the Rio Negro[22] forming what Brazilians call the Amazon at the Meeting of Waters (Portuguese: Encontro das Águas) at Manaus, the largest city on the river.

The Amazon River has an average discharge of about 215,000 m3/s (7,600,000 cu ft/s)–230,000 m3/s (8,100,000 cu ft/s)—approximately 6,591 km3 (1,581 cu mi)– 7,570 km3 (1,820 cu mi) per year, greater than the next seven largest independent rivers combined. Two of the top ten rivers by discharge are tributaries of the Amazon river. The Amazon represents 20% of the global riverine discharge into oceans.[23] The Amazon basin is the largest drainage basin in the world, with an area of approximately 7,000,000 km2 (2,700,000 sq mi).[2] The portion of the river’s drainage basin in Brazil alone is larger than any other river’s basin. The Amazon enters Brazil with only one-fifth of the flow it finally discharges into the Atlantic Ocean, yet already has a greater flow at this point than the discharge of any other river.[24][25]

Etymology[edit]

The Amazon was initially known by Europeans as the Marañón, and the Peruvian part of the river is still known by that name today. It later became known as Rio Amazonas in Spanish and Portuguese.

The name Rio Amazonas was reportedly given after native warriors attacked a 16th-century expedition by Francisco de Orellana. The warriors were led by women, reminding de Orellana of the Amazon warriors, a tribe of women warriors related to Iranian Scythians and Sarmatians[26][27] mentioned in Greek mythology.

The word Amazon itself may be derived from the Iranian compound *ha-maz-an- «(one) fighting together»[28] or ethnonym *ha-mazan- «warriors», a word attested indirectly through a derivation, a denominal verb in Hesychius of Alexandria’s gloss «ἁμαζακάραν· πολεμεῖν. Πέρσαι» («hamazakaran: ‘to make war’ in Persian»), where it appears together with the Indo-Iranian root *kar- «make» (from which Sanskrit karma is also derived).[29]

Other scholars[who?] claim that the name is derived from the Tupi word amassona, meaning «boat destroyer»/[30]

History[edit]

Geological history[edit]

Recent geological studies suggest that for millions of years the Amazon River used to flow in the opposite direction — from east to west. Eventually the Andes Mountains formed, blocking its flow to the Pacific Ocean, and causing it to switch directions to its current mouth in the Atlantic Ocean.[31]

Pre-Columbian era[edit]

Old drawing (from 1879) of Arapaima fishing at the Amazon river.

During what many archaeologists called the formative stage, Amazonian societies were deeply involved in the emergence of South America’s highland agrarian systems. The trade with Andean civilizations in the terrains of the headwaters in the Andes formed an essential contribution to the social and religious development of higher-altitude civilizations like the Muisca and Incas. Early human settlements were typically based on low-lying hills or mounds.

Shell mounds were the earliest evidence of habitation; they represent piles of human refuse (waste) and are mainly dated between 7500 and 4000 years BC. They are associated with ceramic age cultures; no preceramic shell mounds have been documented so far by archaeologists.[32] Artificial earth platforms for entire villages are the second type of mounds. They are best represented by the Marajoara culture. Figurative mounds are the most recent types of occupation.

There is ample evidence that the areas surrounding the Amazon River were home to complex and large-scale indigenous societies, mainly chiefdoms who developed towns and cities.[33] Archaeologists estimate that by the time the Spanish conquistador De Orellana traveled across the Amazon in 1541, more than 3 million indigenous people lived around the Amazon.[34] These pre-Columbian settlements created highly developed civilizations. For instance, pre-Columbian indigenous people on the island of Marajó may have developed social stratification and supported a population of 100,000 people. To achieve this level of development, the indigenous inhabitants of the Amazon rainforest altered the forest’s ecology by selective cultivation and the use of fire. Scientists argue that by burning areas of the forest repeatedly, the indigenous people caused the soil to become richer in nutrients. This created dark soil areas known as terra preta de índio («Indian dark earth»).[35] Because of the terra preta, indigenous communities were able to make land fertile and thus sustainable for the large-scale agriculture needed to support their large populations and complex social structures. Further research has hypothesized that this practice began around 11,000 years ago. Some say that its effects on forest ecology and regional climate explain the otherwise inexplicable band of lower rainfall through the Amazon basin.[35]

Many indigenous tribes engaged in constant warfare. According to James S. Olson, «The Munduruku expansion (in the 18th century) dislocated and displaced the Kawahíb, breaking the tribe down into much smaller groups … [Munduruku] first came to the attention of Europeans in 1770 when they began a series of widespread attacks on Brazilian settlements along the Amazon River.»[36]

Arrival of Europeans[edit]

Amazon tributaries near Manaus

In March 1500, Spanish conquistador Vicente Yáñez Pinzón was the first documented European to sail up the Amazon River.[37] Pinzón called the stream Río Santa María del Mar Dulce, later shortened to Mar Dulce, literally, sweet sea, because of its freshwater pushing out into the ocean. Another Spanish explorer, Francisco de Orellana, was the first European to travel from the origins of the upstream river basins, situated in the Andes, to the mouth of the river. In this journey, Orellana baptized some of the affluents of the Amazonas like Rio Negro, Napo and Jurua.

The name Amazonas is thought to be taken from the native warriors that attacked this expedition, mostly women, that reminded De Orellana of the mythical female Amazon warriors from the ancient Hellenic culture in Greece (see also Origin of the name).

Exploration[edit]

Gonzalo Pizarro set off in 1541 to explore east of Quito into the South American interior in search of El Dorado, the «city of gold» and La Canela, the «valley of cinnamon».[38] He was accompanied by his second-in-command Francisco de Orellana. After 170 km (106 mi), the Coca River joined the Napo River (at a point now known as Puerto Francisco de Orellana); the party stopped for a few weeks to build a boat just upriver from this confluence. They continued downriver through an uninhabited area, where they could not find food. Orellana offered and was ordered to follow the Napo River, then known as Río de la Canela («Cinnamon River»), and return with food for the party. Based on intelligence received from a captive native chief named Delicola, they expected to find food within a few days downriver by ascending another river to the north.

De Orellana took about 57 men, the boat, and some canoes and left Pizarro’s troops on 26 December 1541. However, De Orellana missed the confluence (probably with the Aguarico) where he was searching supplies for his men. By the time he and his men reached another village, many of them were sick from hunger and eating «noxious plants», and near death. Seven men died in that village. His men threatened to mutiny if the expedition turned back to attempt to rejoin Pizarro, the party being over 100 leagues downstream at this point. He accepted to change the purpose of the expedition to discover new lands in the name of the king of Spain, and the men built a larger boat in which to navigate downstream. After a journey of 600 km (370 mi) down the Napo River, they reached a further major confluence, at a point near modern Iquitos, and then followed the upper Amazon, now known as the Solimões, for a further 1,200 km (746 mi) to its confluence with the Rio Negro (near modern Manaus), which they reached on 3 June 1542.

Regarding the initial mission of finding cinnamon, Pizarro reported to the king that they had found cinnamon trees, but that they could not be profitably harvested. True cinnamon (Cinnamomum Verum) is not native to South America. Other related cinnamon-containing plants (of the family Lauraceae) are fairly common in that part of the Amazon and Pizarro probably saw some of these. The expedition reached the mouth of the Amazon on 24 August 1542, demonstrating the practical navigability of the Great River.

In 1560, another Spanish conquistador, Lope de Aguirre, may have made the second descent of the Amazon. Historians are uncertain whether the river he descended was the Amazon or the Orinoco River, which runs more or less parallel to the Amazon further north.

Portuguese explorer Pedro Teixeira was the first European to travel up the entire river. He arrived in Quito in 1637, and returned via the same route.[39]

From 1648 to 1652, Portuguese Brazilian bandeirante António Raposo Tavares led an expedition from São Paulo overland to the mouth of the Amazon, investigating many of its tributaries, including the Rio Negro, and covering a distance of over 10,000 km (6,200 mi).

In what is currently in Brazil, Ecuador, Bolivia, Colombia, Peru, and Venezuela, several colonial and religious settlements were established along the banks of primary rivers and tributaries for trade, slaving, and evangelization among the indigenous peoples of the vast rainforest, such as the Urarina. In the late 1600s, Czech Jesuit Father Samuel Fritz, an apostle of the Omagus established some forty mission villages. Fritz proposed that the Marañón River must be the source of the Amazon, noting on his 1707 map that the Marañón «has its source on the southern shore of a lake that is called Lauricocha, near Huánuco.» Fritz reasoned that the Marañón is the largest river branch one encounters when journeying upstream, and lies farther to the west than any other tributary of the Amazon. For most of the 18th–19th centuries and into the 20th century, the Marañón was generally considered the source of the Amazon.[40]

Scientific exploration[edit]

Early scientific, zoological, and botanical exploration of the Amazon River and basin took place from the 18th century through the first half of the 19th century.

- Charles Marie de La Condamine explored the river in 1743.[41]

- Alexander von Humboldt, 1799–1804

- Johann Baptist von Spix and Carl Friedrich Philipp von Martius, 1817–1820

- Georg von Langsdorff, 1826–1828

- Henry Walter Bates and Alfred Russel Wallace, 1848–1859

- Richard Spruce, 1849–1864

Post-colonial exploitation and settlement[edit]

Amazon Theatre opera house in Manaus built in 1896 during the rubber boom

The Cabanagem revolt (1835–1840) was directed against the white ruling class. It is estimated that from 30% to 40% of the population of Grão-Pará, estimated at 100,000 people, died.[42]

The population of the Brazilian portion of the Amazon basin in 1850 was perhaps 300,000, of whom about 175,000 were Europeans and 25,000 were slaves. The Brazilian Amazon’s principal commercial city, Pará (now Belém), had from 10,000 to 12,000 inhabitants, including slaves. The town of Manáos, now Manaus, at the mouth of the Rio Negro, had a population between 1,000 and 1,500. All the remaining villages, as far up as Tabatinga, on the Brazilian frontier of Peru, were relatively small.[43]

On 6 September 1850, Emperor Pedro II of Brazil sanctioned a law authorizing steam navigation on the Amazon and gave the Viscount of Mauá (Irineu Evangelista de Sousa) the task of putting it into effect. He organised the «Companhia de Navegação e Comércio do Amazonas» in Rio de Janeiro in 1852; in the following year it commenced operations with four small steamers, the Monarca (‘Monarch’), the Cametá, the Marajó and the Rio Negro.[43][44]

At first, navigation was principally confined to the main river; and even in 1857 a modification of the government contract only obliged the company to a monthly service between Pará and Manaus, with steamers of 200 tons cargo capacity, a second line to make six round voyages a year between Manaus and Tabatinga, and a third, two trips a month between Pará and Cametá.[43] This was the first step in opening up the vast interior.

The success of the venture called attention to the opportunities for economic exploitation of the Amazon, and a second company soon opened commerce on the Madeira, Purús, and Negro; a third established a line between Pará and Manaus, and a fourth found it profitable to navigate some of the smaller streams. In that same period, the Amazonas Company was increasing its fleet. Meanwhile, private individuals were building and running small steam craft of their own on the main river as well as on many of its tributaries.[43]

On 31 July 1867, the government of Brazil, constantly pressed by the maritime powers and by the countries encircling the upper Amazon basin, especially Peru, decreed the opening of the Amazon to all countries, but they limited this to certain defined points: Tabatinga – on the Amazon; Cametá – on the Tocantins; Santarém – on the Tapajós; Borba – on the Madeira, and Manaus – on the Rio Negro. The Brazilian decree took effect on 7 September 1867.[43]

Thanks in part to the mercantile development associated with steamboat navigation coupled with the internationally driven demand for natural rubber, the Peruvian city of Iquitos became a thriving, cosmopolitan center of commerce. Foreign companies settled in Iquitos, from where they controlled the extraction of rubber. In 1851 Iquitos had a population of 200, and by 1900 its population reached 20,000. In the 1860s, approximately 3,000 tons of rubber were being exported annually, and by 1911 annual exports had grown to 44,000 tons, representing 9.3% of Peru’s exports.[45] During the rubber boom it is estimated that diseases brought by immigrants, such as typhus and malaria, killed 40,000 native Amazonians.[46]

The first direct foreign trade with Manaus commenced around 1874. Local trade along the river was carried on by the English successors to the Amazonas Company—the Amazon Steam Navigation Company—as well as numerous small steamboats, belonging to companies and firms engaged in the rubber trade, navigating the Negro, Madeira, Purús, and many other tributaries,[43] such as the Marañón, to ports as distant as Nauta, Peru.

By the turn of the 20th century, the exports of the Amazon basin were India-rubber, cacao beans, Brazil nuts and a few other products of minor importance, such as pelts and exotic forest produce (resins, barks, woven hammocks, prized bird feathers, live animals) and extracted goods, such as lumber and gold.

20th-century development[edit]

Since colonial times, the Portuguese portion of the Amazon basin has remained a land largely undeveloped by agriculture and occupied by indigenous people who survived the arrival of European diseases.

Four centuries after the European discovery of the Amazon river, the total cultivated area in its basin was probably less than 65 km2 (25 sq mi), excluding the limited and crudely cultivated areas among the mountains at its extreme headwaters.[47] This situation changed dramatically during the 20th century.

Wary of foreign exploitation of the nation’s resources, Brazilian governments in the 1940s set out to develop the interior, away from the seaboard where foreigners owned large tracts of land. The original architect of this expansion was president Getúlio Vargas, with the demand for rubber from the Allied forces in World War II providing funding for the drive.

In the 1960s, economic exploitation of the Amazon basin was seen as a way to fuel the «economic miracle» occurring at the time. This resulted in the development of «Operation Amazon», an economic development project that brought large-scale agriculture and ranching to Amazonia. This was done through a combination of credit and fiscal incentives.[48]

However, in the 1970s the government took a new approach with the National Integration Program (PIN). A large-scale colonization program saw families from northeastern Brazil relocated to the «land without people» in the Amazon Basin. This was done in conjunction with infrastructure projects mainly the Trans-Amazonian Highway (Transamazônica).[48]

The Trans-Amazonian Highway’s three pioneering highways were completed within ten years but never fulfilled their promise. Large portions of the Trans-Amazonian and its accessory roads, such as BR-317 (Manaus-Porto Velho), are derelict and impassable in the rainy season. Small towns and villages are scattered across the forest, and because its vegetation is so dense, some remote areas are still unexplored.

Many settlements grew along the road from Brasília to Belém with the highway and National Integration Program, however, the program failed as the settlers were unequipped to live in the delicate rainforest ecosystem. This, although the government believed it could sustain millions, instead could sustain very few.[49]

With a population of 1.9 million people in 2014, Manaus is the largest city on the Amazon. Manaus alone makes up approximately 50% of the population of the largest Brazilian state of Amazonas. The racial makeup of the city is 64% pardo (mulatto and mestizo) and 32% white.[50]

Although the Amazon river remains undammed, around 412 dams are in operation in the Amazon’s tributary rivers. From these 412 dams, 151 are constructed over six of the main tributary rivers that drain into the Amazon.[51] Since only 4% of the Amazon’s hydropower potential has been developed in countries like Brazil,[52] more damming projects are underway and hundreds more are planned.[53] After witnessing the negative effects of environmental degradation, sedimentation, navigation and flood control caused by the Three Gorges Dam in the Yangtze River,[54] scientists are worried that constructing more dams in the Amazon will harm its biodiversity in the same way by «blocking fish-spawning runs, reducing the flows of vital oil nutrients and clearing forests».[53] Damming the Amazon River could potentially bring about the «end of free flowing rivers» and contribute to an «ecosystem collapse» that will cause major social and environmental problems.[51]

Course[edit]

Origins[edit]

The Amazon was thought to originate from the Apacheta cliff in Arequipa at the Nevado Mismi, marked only by a wooden cross.

Nevado Mismi, formerly considered to be the source of the Amazon

The most distant source of the Amazon was thought to be in the Apurímac river drainage for nearly a century. Such studies continued to be published even recently, such as in 1996,[55] 2001,[56] 2007,[18] and 2008,[57] where various authors identified the snowcapped 5,597 m (18,363 ft) Nevado Mismi peak, located roughly 160 km (99 mi) west of Lake Titicaca and 700 km (430 mi) southeast of Lima, as the most distant source of the river. From that point, Quebrada Carhuasanta emerges from Nevado Mismi, joins Quebrada Apacheta and soon forms Río Lloqueta which becomes Río Hornillos and eventually joins the Río Apurímac.

A 2014 study by Americans James Contos and Nicolas Tripcevich in Area, a peer-reviewed journal of the Royal Geographical Society, however, identifies the most distant source of the Amazon as actually being in the Río Mantaro drainage.[21] A variety of methods were used to compare the lengths of the Mantaro river vs. the Apurímac river from their most distant source points to their confluence, showing the longer length of the Mantaro. Then distances from Lago Junín to several potential source points in the uppermost Mantaro river were measured, which enabled them to determine that the Cordillera Rumi Cruz was the most distant source of water in the Mantaro basin (and therefore in the entire Amazon basin). The most accurate measurement method was direct GPS measurement obtained by kayak descent of each of the rivers from their source points to their confluence (performed by Contos). Obtaining these measurements was difficult given the class IV–V nature of each of these rivers, especially in their lower «Abyss» sections. Ultimately, they determined that the most distant point in the Mantaro drainage is nearly 80 km farther upstream compared to Mt. Mismi in the Apurímac drainage, and thus the maximal length of the Amazon river is about 80 km longer than previously thought. Contos continued downstream to the ocean and finished the first complete descent of the Amazon river from its newly identified source (finishing November 2012), a journey repeated by two groups after the news spread.[58]

After about 700 km (430 mi), the Apurímac then joins Río Mantaro to form the Ene, which joins the Perene to form the Tambo, which joins the Urubamba River to form the Ucayali. After the confluence of Apurímac and Ucayali, the river leaves Andean terrain and is surrounded by floodplain. From this point to the confluence of the Ucayali and the Marañón, some 1,600 km (990 mi), the forested banks are just above the water and are inundated long before the river attains its maximum flood stage.[43] The low river banks are interrupted by only a few hills, and the river enters the enormous Amazon rainforest.

The Upper Amazon or Solimões[edit]

Although the Ucayali–Marañón confluence is the point at which most geographers place the beginning of the Amazon River proper, in Brazil the river is known at this point as the Solimões das Águas. The river systems and flood plains in Brazil, Peru, Ecuador, Colombia, and Venezuela, whose waters drain into the Solimões and its tributaries, are called the «Upper Amazon».

The Amazon proper runs mostly through Brazil and Peru, and is part of the border between Colombia and Perú. It has a series of major tributaries in Colombia, Ecuador and Peru, some of which flow into the Marañón and Ucayali, and others directly into the Amazon proper. These include rivers Putumayo, Caquetá, Vaupés, Guainía, Morona, Pastaza, Nucuray, Urituyacu, Chambira, Tigre, Nanay, Napo, and Huallaga.

At some points, the river divides into anabranches, or multiple channels, often very long, with inland and lateral channels, all connected by a complicated system of natural canals, cutting the low, flat igapó lands, which are never more than 5 m (16 ft) above low river, into many islands.[59]

From the town of Canaria at the great bend of the Amazon to the Negro, vast areas of land are submerged at high water, above which only the upper part of the trees of the sombre forests appear. Near the mouth of the Rio Negro to Serpa, nearly opposite the river Madeira, the banks of the Amazon are low, until approaching Manaus, they rise to become rolling hills.[43]

The Lower Amazon[edit]

The Lower Amazon begins where the darkly colored waters of the Rio Negro meets the sandy-colored Rio Solimões (the upper Amazon), and for over 6 km (3.7 mi) these waters run side by side without mixing. At Óbidos, a bluff 17 m (56 ft) above the river is backed by low hills. The lower Amazon seems to have once been a gulf of the Atlantic Ocean, the waters of which washed the cliffs near Óbidos.

Only about 10% of the Amazon’s water enters downstream of Óbidos, very little of which is from the northern slope of the valley. The drainage area of the Amazon basin above Óbidos city is about 5,000,000 km2 (1,900,000 sq mi), and, below, only about 1,000,000 km2 (390,000 sq mi) (around 20%), exclusive of the 1,400,000 km2 (540,000 sq mi) of the Tocantins basin.[43] The Tocantins River enters the southern portion of the Amazon delta.

In the lower reaches of the river, the north bank consists of a series of steep, table-topped hills extending for about 240 km (150 mi) from opposite the mouth of the Xingu as far as Monte Alegre. These hills are cut down to a kind of terrace which lies between them and the river.[59]

On the south bank, above the Xingu, a line of low bluffs bordering the floodplain extends nearly to Santarém in a series of gentle curves before they bend to the southwest, and, abutting upon the lower Tapajós, merge into the bluffs which form the terrace margin of the Tapajós river valley.[60]

Mouth[edit]

Satellite image of the mouth of the Amazon River, from the north looking south

Belém is the major city and port at the mouth of the river at the Atlantic Ocean. The definition of where exactly the mouth of the Amazon is located, and how wide it is, is a matter of dispute, because of the area’s peculiar geography. The Pará and the Amazon are connected by a series of river channels called furos near the town of Breves; between them lies Marajó, the world’s largest combined river/sea island.

If the Pará river and the Marajó island ocean frontage are included, the Amazon estuary is some 325 km (202 mi) wide.[61] In this case, the width of the mouth of the river is usually measured from Cabo Norte, the cape located straight east of Pracuúba in the Brazilian state of Amapá, to Ponta da Tijoca near the town of Curuçá, in the state of Pará.

A more conservative measurement excluding the Pará river estuary, from the mouth of the Araguari River to Ponta do Navio on the northern coast of Marajó, would still give the mouth of the Amazon a width of over 180 km (112 mi). If only the river’s main channel is considered, between the islands of Curuá (state of Amapá) and Jurupari (state of Pará), the width falls to about 15 km (9.3 mi).

The plume generated by the river’s discharge covers up to 1.3 million km2 and is responsible for muddy bottoms influencing a wide area of the tropical north Atlantic in terms of salinity, pH, light penetration, and sedimentation.[23]

Lack of bridges[edit]

There are no bridges across the entire width of the river.[62] This is not because the river would be too wide to bridge; for most of its length, engineers could build a bridge across the river easily. For most of its course, the river flows through the Amazon Rainforest, where there are very few roads and cities. Most of the time, the crossing can be done by a ferry. The Manaus Iranduba Bridge linking the cities of Manaus and Iranduba spans the Rio Negro, the second-largest tributary of the Amazon, just before their confluence.

Dispute regarding length[edit]

While debate as to whether the Amazon or the Nile is the world’s longest river has gone on for many years, the historic consensus of geographic authorities has been to regard the Amazon as the second longest river in the world, with the Nile being the longest. However, the Amazon has been reported as being anywhere between 6,275 km (3,899 mi) and 6,992 km (4,345 mi) long.[3] It is often said to be «at least» 6,575 km (4,086 mi) long.[2] The Nile is reported to be anywhere from 5,499 to 7,088 km (3,417 to 4,404 mi).[3] Often it is said to be «about» 6,650 km (4,130 mi) long.[17] There are several factors that can affect these measurements, such as the position of the geographical source and the mouth, the scale of measurement, and the length measuring techniques (for details see also List of rivers by length).[3][4]

In July 2008, the Brazilian Institute for Space Research (INPE) published a news article on their webpage, claiming that the Amazon River was 140 km (87 mi) longer than the Nile. The Amazon’s length was calculated as 6,992 km (4,345 mi), taking the Apacheta Creek as its source. Using the same techniques, the length of the Nile was calculated as 6,853 km (4,258 mi), which is longer than previous estimates but still shorter than the Amazon. The results were reached by measuring the Amazon downstream to the beginning of the tidal estuary of Canal do Sul and then, after a sharp turn back, following tidal canals surrounding the isle of Marajó and finally including the marine waters of the Río Pará bay in its entire length.[57][20] According to an earlier article on the webpage of the National Geographic, the Amazon’s length was calculated as 6,800 km (4,200 mi) by a Brazilian scientist. In June 2007, Guido Gelli, director of science at the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE), told London’s Telegraph Newspaper that it could be considered that the Amazon was the longest river in the world.[63] However, according to the above sources, none of the two results was published, and questions were raised about the researchers’ methodology. In 2009, a peer-reviewed article, was published, concluding that the Nile is longer than the Amazon by stating a length of 7,088 km (4,404 mi) for the Nile and 6,575 km (4,086 mi) for the Amazon, measured by using a combination of satellite image analysis and field investigations to the source regions.[3]

According to the Encyclopædia Britannica, the final length of the Amazon remains open to interpretation and continued debate.[2][20]

Watershed[edit]

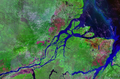

The Amazon basin, the largest in the world, covers about 40% of South America, an area of approximately 7,050,000 km2 (2,720,000 sq mi). It drains from west to east, from Iquitos in Peru, across Brazil to the Atlantic. It gathers its waters from 5 degrees north latitude to 20 degrees south latitude. Its most remote sources are found on the inter-Andean plateau, just a short distance from the Pacific Ocean.[64]

The Amazon River and its tributaries are characterised by extensive forested areas that become flooded every rainy season. Every year, the river rises more than 9 m (30 ft), flooding the surrounding forests, known as várzea («flooded forests»). The Amazon’s flooded forests are the most extensive example of this habitat type in the world.[65] In an average dry season, 110,000 km2 (42,000 sq mi) of land are water-covered, while in the wet season, the flooded area of the Amazon basin rises to 350,000 km2 (140,000 sq mi).[61]

The quantity of water released by the Amazon to the Atlantic Ocean is enormous: up to 300,000 m3/s (11,000,000 cu ft/s) in the rainy season, with an average of 209,000 m3/s (7,400,000 cu ft/s) from 1973 to 1990.[66] The Amazon is responsible for about 20% of the Earth’s fresh water entering the ocean.[65] The river pushes a vast plume of fresh water into the ocean. The plume is about 400 km (250 mi) long and between 100 and 200 km (62 and 124 mi) wide. The fresh water, being lighter, flows on top of the seawater, diluting the salinity and altering the colour of the ocean surface over an area up to 2,500,000 km2 (970,000 sq mi) in extent. For centuries ships have reported fresh water near the Amazon’s mouth yet well out of sight of land in what otherwise seemed to be the open ocean.[25]

The Atlantic has sufficient wave and tidal energy to carry most of the Amazon’s sediments out to sea, thus the Amazon does not form a true delta. The great deltas of the world are all in relatively protected bodies of water, while the Amazon empties directly into the turbulent Atlantic.[22]

There is a natural water union between the Amazon and the Orinoco basins, the so-called Casiquiare canal. The Casiquiare is a river distributary of the upper Orinoco, which flows southward into the Rio Negro, which in turn flows into the Amazon. The Casiquiare is the largest river on earth that links two major river systems, a so-called bifurcation.

Flooding[edit]

NASA satellite image of a flooded portion of the river

Not all of the Amazon’s tributaries flood at the same time of the year. Many branches begin flooding in November and might continue to rise until June. The rise of the Rio Negro starts in February or March and begins to recede in June. The Madeira River rises and falls two months earlier than most of the rest of the Amazon river.

The depth of the Amazon between Manacapuru and Óbidos has been calculated as between 20 to 26 m (66 to 85 ft). At Manacapuru, the Amazon’s water level is only about 24 m (79 ft) above mean sea level. More than half of the water in the Amazon downstream of Manacapuru is below sea level.[67] In its lowermost section, the Amazon’s depth averages 20 to 50 m (66 to 164 ft), in some places as much as 100 m (330 ft).[68]

The main river is navigable for large ocean steamers to Manaus, 1,500 km (930 mi) upriver from the mouth. Smaller ocean vessels below 9000 tons and with less than 5.5 m (18 ft) draft can reach as far as Iquitos, Peru, 3,600 km (2,200 mi) from the sea. Smaller riverboats can reach 780 km (480 mi) higher, as far as Achual Point. Beyond that, small boats frequently ascend to the Pongo de Manseriche, just above Achual Point in Peru.[59]

Annual flooding occurs in late northern latitude winter at high tide when the incoming waters of the Atlantic are funnelled into the Amazon delta. The resulting undular tidal bore is called the pororoca, with a leading wave that can be up to 7.6 m (25 ft) high and travel up to 800 km (500 mi) inland.[69][70]

Geology[edit]

The Amazon River originated as a transcontinental river in the Miocene epoch between 11.8 million and 11.3 million years ago and took its present shape approximately 2.4 million years ago in the Early Pleistocene.

The proto-Amazon during the Cretaceous flowed west, as part of a proto-Amazon-Congo river system, from the interior of present-day Africa when the continents were connected, forming western Gondwana. 80 million years ago, the two continents split. Fifteen million years ago, the main tectonic uplift phase of the Andean chain started. This tectonic movement is caused by the subduction of the Nazca Plate underneath the South American Plate. The rise of the Andes and the linkage of the Brazilian and Guyana bedrock shields,[clarification needed] blocked the river and caused the Amazon Basin to become a vast inland sea. Gradually, this inland sea became a massive swampy, freshwater lake and the marine inhabitants adapted to life in freshwater.[71]

Eleven to ten million years ago, waters worked through the sandstone from the west and the Amazon began to flow eastward, leading to the emergence of the Amazon rainforest. During glacial periods, sea levels dropped and the great Amazon lake rapidly drained and became a river, which would eventually become the disputed world’s longest, draining the most extensive area of rainforest on the planet.[72]

Paralleling the Amazon River is a large aquifer, dubbed the Hamza River, the discovery of which was made public in August 2011.[73]

Protected areas[edit]

| Name | Country | Coordinates | Image | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Allpahuayo-Mishana National Reserve | Peru | 3°56′S 73°33′W / 3.933°S 73.550°W |

|

[74] |

| Amacayacu National Park | Colombia | 3°29′S 72°12′W / 3.483°S 72.200°W |

|

[75] |

| Amazônia National Park | Brazil | 4°26′S 56°50′W / 4.433°S 56.833°W |

|

[76] |

| Anavilhanas National Park | Brazil | 2°23′S 60°55′W / 2.383°S 60.917°W |

|

[77] |

Flora and fauna[edit]

Flora[edit]

|

This section is empty. You can help by adding to it. (February 2017) |

Fauna[edit]

The tambaqui, an important species in Amazonian fisheries, breeds in the Amazon River

More than one-third of all known species in the world live in the Amazon rainforest.[78] It is the richest tropical forest in the world in terms of biodiversity.[79] In addition to thousands of species of fish, the river supports crabs, algae, and turtles.

Mammals[edit]

Along with the Orinoco, the Amazon is one of the main habitats of the boto, also known as the Amazon river dolphin (Inia geoffrensis). It is the largest species of river dolphin, and it can grow to lengths of up to 2.6 m (8.5 ft). The colour of its skin changes with age; young animals are gray, but become pink and then white as they mature. The dolphins use echolocation to navigate and hunt in the river’s tricky depths.[80] The boto is the subject of a legend in Brazil about a dolphin that turns into a man and seduces maidens by the riverside.[81]

The tucuxi (Sotalia fluviatilis), also a dolphin species, is found both in the rivers of the Amazon basin and in the coastal waters of South America. The Amazonian manatee (Trichechus inunguis), also known as «seacow», is found in the northern Amazon River basin and its tributaries. It is a mammal and a herbivore. Its population is limited to freshwater habitats, and, unlike other manatees, it does not venture into saltwater. It is classified as vulnerable by the International Union for Conservation of Nature.[82]

The Amazon and its tributaries are the main habitat of the giant otter (Pteronura brasiliensis).[83] Sometimes known as the «river wolf,» it is one of South America’s top carnivores. Because of habitat destruction and hunting, its population has dramatically decreased. It is now listed on Appendix I of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES), which effectively bans international trade.[84]

Reptiles[edit]

|

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (February 2017) |

The Anaconda is found in shallow waters in the Amazon basin. One of the world’s largest species of snake, the anaconda spends most of its time in the water with just its nostrils above the surface. Species of caimans, that are related to alligators and other crocodilians, also inhabit the Amazon as do varieties of turtles.[85]

Birds[edit]

The types of birds that pass by or live in the amazon river are toucans, harpy eagles, and much more variations of birds.

|

This section is empty. You can help by adding to it. (February 2017) |

Fish[edit]

Neon tetra is one of the most popular aquarium fish

The Amazonian fish fauna is the centre of diversity for neotropical fishes, some of which are popular aquarium specimens like the neon tetra and the freshwater angelfish. More than 5,600 species were known as of 2011, and approximately fifty new species are discovered each year.[86][87] The arapaima, known in Brazil as the pirarucu, is a South American tropical freshwater fish, one of the largest freshwater fish in the world, with a length of up to 15 feet (4.6 m).[88] Another Amazonian freshwater fish is the arowana (or aruanã in Portuguese), such as the silver arowana (Osteoglossum bicirrhosum), which is a predator and very similar to the arapaima, but only reaches a length of 120 cm (47 in). Also present in large numbers is the notorious piranha, an omnivorous fish that congregates in large schools and may attack livestock. There are approximately 30 to 60 species of piranha. The candirú, native to the Amazon River, is a species of parasitic fresh water catfish in the family Trichomycteridae,[89] just one of more than 1200 species of catfish in the Amazon basin. Other catfish ‘walk’ overland on their ventral fins,[90] while the kumakuma (Brachyplatystoma filamentosum), aka piraiba or «goliath catfish», can reach 3.6 m (12 ft) in length and 200 kg (440 lb) in weight.[91]

The electric eel (Electrophorus electricus) and more than 100 species of electric fishes (Gymnotiformes) inhabit the Amazon basin. River stingrays (Potamotrygonidae) are also known. The bull shark (Carcharhinus leucas) has been reported 4,000 km (2,500 mi) up the Amazon River at Iquitos in Peru.[92]

Butterflies[edit]

Microbiota[edit]

Freshwater microbes are generally not very well known, even less so for a pristine ecosystem like the Amazon. Recently, metagenomics has provided answers to what kind of microbes inhabit the river.[93] The most important microbes in the Amazon River are Actinomycetota, Alphaproteobacteria, Betaproteobacteria, Gammaproteobacteria and Thermoproteota.

Major tributaries[edit]

Solimões, the section of the upper Amazon River

Aerial view of an Amazon tributary

The Amazon has over 1,100 tributaries, twelve of which are over 1,500 km (930 mi) long.[94] Some of the more notable ones are:

- Branco

- Casiquiare canal

- Caquetá

- Huallaga

- Putumayo (or Içá River)

- Javary (or Yavarí)

- Juruá

- Madeira

- Marañón

- Morona

- Nanay

- Napo

- Negro

- Pastaza

- Purús

- Tambo

- Tapajós

- Tigre

- Tocantins

- Trombetas

- Ucayali

- Xingu

- Yapura

List of major tributaries[edit]

The main river and tributaries are (sorted in order from the confluence of Ucayali and Marañón rivers to the mouth):

| Left tributary | Right tributary | Length (km) | Basin size (km²) | Average discharge (m3/s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Upper Amazon

(Confluence of Ucayali and Marañón rivers — Tabatinga) |

||||

| Marañón | 2,112 | 364,873.4 | 16,708 | |

| Ucayali | 2,738 | 353,729.3 | 13,630.1 | |

| Tahuyo | 80 | 1,630 | 105.7 | |

| Tamshiyaçu | 86.7 | 1,367.3 | 86.5 | |

| Itaya | 213 | 2,668 | 161.4 | |

| Nanay | 483 | 16,673.4 | 1,072.7 | |

| Maniti | 198.7 | 2,573.6 | 180.4 | |

| Napo | 1,075 | 103,307.8 | 7,147.8 | |

| Apayaçu | 50 | 2,393.6 | 160.9 | |

| Orosa | 95 | 3,506.8 | 234.3 | |

| Ampiyaçu | 140 | 4,201.4 | 267.2 | |

| Chichita | 48 | 1,314.2 | 87.7 | |

| Cochiquinas | 49 | 2,362.7 | 150.2 | |

| Santa Rosa | 45 | 1,678 | 101.5 | |

| Cajocumal | 58 | 2,094.9 | 141.5 | |

| Atacuari | 108 | 3,480.5 | 236.8 | |

| Middle Amazon

(Tabatinga — Encontro das Águas) |

||||

| Javary | 1,056 | 99,674.1 | 5,222.5 | |

| Igarapé

Veneza |

943.9 | 58.3 | ||

| Tacana | 541 | 35.5 | ||

| Igarapé de

Belém |

1,299.9 | 85.4 | ||

| Igarapé São

Jerônimo |

1,259.6 | 78.2 | ||

| Jandiatuba | 520 | 14,890.4 | 980 | |

| Igarapé

Acuruy |

2,462.1 | 127.1 | ||

| Putumayo | 1,813 | 121,115.8 | 8,519.9 | |

| Tonantins | 2,955.2 | 169.2 | ||

| Jutai | 1,488 | 78,451.5 | 4,000 | |

| Juruá | 3,283 | 190,573 | 6,662.1 | |

| Uarini | 7,195.8 | 432.9 | ||

| Japurá | 2,816 | 276,812 | 18,121.6 | |

| Tefé | 571 | 24,375.5 | 1,190.4 | |

| Caiambe | 2,650.1 | 90 | ||

| Parana Copea | 10,532.3 | 423.8 | ||

| Coari | 599 | 35,741.3 | 1,389.3 | |

| Mamiá | 5,514 | 176.2 | ||

| Badajos | 413 | 21,575 | 1,300 | |

| Igarapé Miuá | 1,294.5 | 56.9 | ||

| Purus | 3,382 | 378,762.4 | 11,206.9 | |

| Paraná Arara | 1,915.7 | 78.2 | ||

| Paraná

Manaquiri |

1,318.6 | 52.9 | ||

| Manacapuru | 291 | 14,103 | 559.5 | |

| Lower Amazon

(Encontro das Águas — Gurupá) |

||||

| Rio Negro | 2,362 | 714,577.6 | 30,640.8 | |

| Prêto da Eva | 3,039.5 | 110.8 | ||

| Igapó-Açu | 500 | 45,994.4 | 1,676.5 | |

| Madeira | 3,380 | 1,322,782.4 | 32,531.9 | |

| Urubu | 430 | 13,892 | 459.8 | |

| Uatumã | 701 | 67,920 | 2,290.8 | |

| Canumã,

Paraná do Urariá |

400 | 127,116 | 4,804.4 | |

| Nhamundá,

Trombetas |

744 | 150,032 | 4,127 | |

| Curuá | 484 | 28,099 | 470.1 | |

| Lago Grande

do Curuaí |

3,293.6 | 92.7 | ||

| Tapajós | 1,992 | 494,551.3 | 13,540 | |

| Curuá-Una | 315 | 24,505 | 729.8 | |

| Maicurú | 546 | 18,546 | 272.3 | |

| Uruará | 104.8 | |||

| Jauari | 76.9 | |||

| Guajará | 4,243 | 105.6 | ||

| Paru de Este | 731 | 39,289 | 970 | |

| Xingu | 2,275 | 513,313.5 | 10,022.6 | |

| Igarapé

Arumanduba |

50.8 | |||

| Jari | 769 | 51,893 | 1,213.5 | |

| Amazon Delta

(river mouth to Gurupá) |

||||

| Braco do

Cajari |

4,732.4 | 157.1 | ||

| Pará | 784 | 84,027 | 3,500.3 | |

| Tocantins | 2,639 | 777,308 | 11,796 | |

| Atuã | 2,769 | 119.8 | ||

| Anajás | 300 | 24,082.5 | 948 | |

| Mazagão | 1,250.2 | 44.4 | ||

| Vila Nova | 5,383.8 | 180.8 | ||

| Matapi | 2,487.4 | 81.7 | ||

| Acará,

Guamá |

400 | 87,389.5 | 2,550.7 | |

| Arari | 1,523.6 | 80.2 | ||

| Pedreira | 2,005 | 89.9 | ||

| Paracauari | 1,390.3 | 67.9 | ||

| Jupati | 724.2 | 32.6 |

[95][96][97][98][99]

List by length[edit]

- 6,400 km (4,000 mi)[2] (6,275 to 7,025 km (3,899 to 4,365 mi))[3] – Amazon, South America

- 3,250 km (2,019 mi) – Madeira, Bolivia/Brazil[100]

- 3,211 km (1,995 mi) – Purús, Peru/Brazil[101]

- 2,820 km (1,752 mi) – Japurá or Caquetá, Colombia/Brazil[102]

- 2,639 km (1,640 mi) – Tocantins, Brazil[103]

- 2,627 km (1,632 mi) – Araguaia, Brazil (tributary of Tocantins)[104]

- 2,400 km (1,500 mi) – Juruá, Peru/Brazil[105]

- 2,250 km (1,400 mi) – Rio Negro, Brazil/Venezuela/Colombia[106]

- 1,992 km (1,238 mi) – Tapajós, Brazil[107]

- 1,979 km (1,230 mi) – Xingu, Brazil[108]

- 1,900 km (1,181 mi) – Ucayali River, Peru[109]

- 1,749 km (1,087 mi) – Guaporé, Brazil/Bolivia (tributary of Madeira)[110]

- 1,575 km (979 mi) – Içá (Putumayo), Ecuador/Colombia/Peru

- 1,415 km (879 mi) – Marañón, Peru

- 1,370 km (851 mi) – Teles Pires, Brazil (tributary of Tapajós)

- 1,300 km (808 mi) – Iriri, Brazil (tributary of Xingu)

- 1,240 km (771 mi) – Juruena, Brazil (tributary of Tapajós)

- 1,130 km (702 mi) – Madre de Dios, Peru/Bolivia (tributary of Madeira)

- 1,100 km (684 mi) – Huallaga, Peru (tributary of Marañón)

List by inflow to the Amazon[edit]

| Rank | Name | Average annual discharge (m^3/s) | % of Amazon |

|---|---|---|---|

| Amazon | 209,000 | 100% | |

| 1 | Madeira | 31,200 | 15% |

| 2 | Negro | 28,400 | 14% |

| 3 | Japurá | 18,620 | 9% |

| 4 | Marañón | 16,708 | 8% |

| 5 | Tapajós | 13,540 | 6% |

| 6 | Ucayali | 13,500 | 5% |

| 7 | Purus | 10,970 | 5% |

| 8 | Xingu | 9,680 | 5% |

| 9 | Putumayo | 8,760 | 4% |

| 10 | Juruá | 8,440 | 4% |

| 11 | Napo | 6,976 | 3% |

| 12 | Javari | 4,545 | 2% |

| 13 | Trombetas | 3,437 | 2% |

| 14 | Jutaí | 3,425 | 2% |

| 15 | Abacaxis | 2,930 | 2% |

| 16 | Uatumã | 2,190 | 1% |

See also[edit]

- Amazon natural region

- Peruvian Amazonia

Notes[edit]

- ^ The length of the Amazon River is usually said to be «at least» 6,400 km (4,000 mi),[2] but reported values lie anywhere between 6,275 and 7,025 km (3,899 and 4,365 mi).[3]

The length measurements of many rivers are only approximations and differ from each other because there are many factors that determine the calculated river length, such as the position of the geographical source and the mouth, the scale of measurement, and the length measuring techniques (for details see also List of rivers by length).[3][4] - ^ The Nile is usually said to be the longest river in the world, with a length of about 6,650 km,[17] and the Amazon the second longest river in the world, with a length of at least 6,400 km.[2] In 2007 and 2008, some scientists claimed that the Amazon has a length of 6,992 km and was longer than the Nile, whose length was calculated as 6,853 km.[18][19] They achieved this result by adding the waterway from the Amazon’s southern outlet through tidal canals and the Pará estuary of the Tocantins.[citation needed]

A peer-reviewed article, published in 2009, states a length of 7,088 km for the Nile and 6,575 km for the Amazon, measured by using a combination of satellite image analysis and field investigations to the source regions.[3]

According to the Encyclopædia Britannica, as of 2020, the length of the Amazon remains open to interpretation and continued debate.[2][20]

References[edit]

- ^ Amazon River at GEOnet Names Server

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j «Amazon River». Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 8 November 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Liu, Shaochuang; Lu, P; Liu, D; Jin, P; Wang, W (1 March 2009). «Pinpointing the sources and measuring the lengths of the principal rivers of the world». Int. J. Digital Earth. 2 (1): 80–87. Bibcode:2009IJDE….2…80L. doi:10.1080/17538940902746082. S2CID 27548511. Archived from the original on 23 December 2018. Retrieved 29 December 2018.

- ^ a b «Where Does the Amazon River Begin?». National Geographic News. 15 February 2014. Archived from the original on 27 March 2019. Retrieved 25 December 2018.

- ^ a b c «CORPOAMAZONIA — TRÁMITES PARA APROVECHAMIENTO FORESTAL» (PDF).

- ^ a b c d e «Issues of local and global use of water from the Amazon».

- ^ a b «Seasonal assessment of groundwater quality in the cities of Itacoatiara and Manacapuru (Amazon, Brazil)».

- ^ «Amazon River-Hidrology».

- ^ «Aguas Amazonicas».

- ^ Pierre, Ribstein; Bernard, Francou; Anne, Coudrain Ribstein; Philippe, Mourguiart (1995). «EAUX, GLACIERS & CHANGEMENTS CLIMATIQUES DANS LES ANDES TROPICALES — Institut Français d’Études Andines — Institut Français de Recherche Scientifique pour le Développement en Cooperation» (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022.

- ^ Seyler, Patrick; Laurence Maurice-Bourgoin; Jean Loup Guyot. «Hydrological Control on the Temporal Variability of Trace Element Concentration in the Amazon River and its Main Tributaries». Geological Survey of Brazil (CPRM). Archived from the original on 21 July 2011. Retrieved 24 July 2010.

- ^ Jacques Callède u. a.: Les apports en eau de l’Amazone à l’Océan Atlantique. In: Revue des sciences de l’eau / Journal of Water Science. Bd. 23, Nr. 3, Montreal 2010, S. 247–273 (retrieved 19 August 2013)

- ^ a b c d «Rivers Network».

- ^ a b c GRDC: Daten des Pegels Óbidos

- ^ a b Jamie, Towner (2019). «Assessing the performance of global hydrological models for capturing peak river flows in the Amazon basin» (PDF).

- ^ Uereyen, Soner; Kuenzer, Claudia (9 December 2019). «A Review of Earth Observation-Based Analyses for Major River Basins». Remote Sensing. 11 (24): 2951. Bibcode:2019RemS…11.2951U. doi:10.3390/rs11242951.

- ^ a b «Nile River». Encyclopædia Britannica. 2010. Archived from the original on 29 April 2015. Retrieved 3 August 2010.

- ^ a b «Amazon river ‘longer than Nile’«. BBC News. 16 June 2007. Archived from the original on 26 September 2010. Retrieved 3 August 2010.

- ^ Roach, John. «Amazon Longer Than Nile River, Scientists Say». National Geographic. Archived from the original on 15 August 2012. Retrieved 4 March 2015.

- ^ a b c «How Long Is the Amazon River?». Encyclopedia Britannica. Archived from the original on 24 December 2018. Retrieved 24 December 2018.

- ^ a b James Contos; Nicholas Tripcevich (March 2014). «Correct placement of the most distant source of the Amazon River in the Mantaro River drainage» (PDF). Area. 46 (1): 27–39. doi:10.1111/area.12069.

- ^ a b Penn, James R. (2001). Rivers of the World. ABC-CLIO. p. 8. ISBN 978-1-57607-042-0.

- ^ a b Moura, Rodrigo L.; Amado-Filho, Gilberto M.; Moraes, Fernando C.; Brasileiro, Poliana S.; Salomon, Paulo S.; Mahiques, Michel M.; Bastos, Alex C.; Almeida, Marcelo G.; Silva, Jomar M.; Araujo, Beatriz F.; Brito, Frederico P.; Rangel, Thiago P.; Oliveira, Braulio C.V.; Bahia, Ricardo G.; Paranhos, Rodolfo P.; Dias, Rodolfo J. S.; Siegle, Eduardo; Figueiredo, Alberto G.; Pereira, Renato C.; Leal, Camellia V.; Hajdu, Eduardo; Asp, Nils E.; Gregoracci, Gustavo B.; Neumann-Leitão, Sigrid; Yager, Patricia L.; Francini-Filho, Ronaldo B.; Fróes, Adriana; Campeão, Mariana; Silva, Bruno S.; Moreira, Ana P.B.; Oliveira, Louisi; Soares, Ana C.; Araujo, Lais; Oliveira, Nara L.; Teixeira, João B.; Valle, Rogerio A.B.; Thompson, Cristiane C.; Rezende, Carlos E.; Thompson, Fabiano L. (1 April 2016). «An extensive reef system at the Amazon River mouth». Science Advances. 2 (4): e1501252. Bibcode:2016SciA….2E1252M. doi:10.1126/sciadv.1501252. PMC 4846441. PMID 27152336.

- ^ Tom Sterling: Der Amazonas. Time-Life Bücher 1979, 7th German Printing, p. 19.

- ^ a b Smith, Nigel J.H. (2003). Amazon Sweet Sea: Land, Life, and Water at the River’s Mouth. University of Texas Press. pp. 1–2. ISBN 978-0-292-77770-5. Archived from the original on 15 September 2015.

- ^ «Apollonius Rhodius, Argonautica, Book 2». Archived from the original on 30 August 2017. Retrieved 15 October 2018.

- ^ «Argonautica Book 2». Archived from the original on 5 October 2018. Retrieved 15 October 2018.

- ^ «Amazon | Origin And Meaning Of Amazon By Online Etymology Dictionary». 2018. Etymonline.Com. Accessed 15 October 2018. [1] Archived 15 October 2018 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Lagercrantz, Xenia Lidéniana (1912), 270ff., cited after Hjalmar Frisk, Greek Etymological Dictionary (1960–1970)

- ^ «Amazon River», Encarta Encyclopedia, Microsoft Student 2009 DVD.

- ^ «Amazon river ‘switched direction’«. 24 October 2006.

- ^ Silberman, Neil Asher; Bauer, Alexander A. (November 2012). The Oxford Companion to Archaeology. OUP USA. p. 429. ISBN 978-0-19-973578-5.

- ^ Roosevelt, Anna Curtenius (1993). «The Rise and Fall of the Amazon Chiefdoms». L’Homme. 33 (126/128): 255–283. doi:10.3406/hom.1993.369640. ISSN 0439-4216. JSTOR 40589896.

- ^ Wohl, 2011, pp. 24–25.

- ^ a b Wohl, 2011, p. 25.

- ^ Olson, James Stuart (1991). The Indians of Central and South America: an ethnohistorical dictionary. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 57–248. ISBN 978-0-313-26387-3. Archived from the original on 12 September 2015.

- ^ Morison, Samuel (1974). The European Discovery of America: The Southern Voyages, 1492–1616. New York: Oxford University Press.

- ^ Francisco de Orellana Francisco de Orellana (Spanish explorer and soldier) Archived 3 May 2009 at the Wayback Machine. Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ^ Graham, Devon. «A Brief History of Amazon Exploration». Project Amazonas. Archived from the original on 25 July 2014. Retrieved 18 July 2014.

- ^ «Camila Loureiro Dias, «Maps and Political Discourse: The Amazon River of Father Samuel Fritz,» The Americas, Volume 69, Number 1, July 2012, pp. 95–116″ (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 1 October 2018. Retrieved 15 September 2018.

- ^ «Charles-Marie de La Condamine (French naturalist and mathematician)». Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Archived from the original on 25 July 2014. Retrieved 18 July 2014.

- ^ Renato Cancian. «Cabanagem (1835–1840): Uma das mais sangrentas rebeliões do período regencial». Universo Online Liçao de Casa (in Portuguese). Archived from the original on 2 November 2007. Retrieved 12 November 2007.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Church 1911, p. 789.

- ^ «Sobre Escravos e Regatões» (PDF) (in Portuguese). Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 11 December 2015.

- ^ Historia del Peru, Editorial Lexus. p. 93.

- ^ La Republica Oligarchic. Editorial Lexus 2000 p. 925.

- ^ Church 1911, p. 790.

- ^ a b Campari, João S. (2005). The Economics of Deforestation in the Amazon: Dispelling the Myths. Edward Elgar Publishing. ISBN 9781845425517. Archived from the original on 30 November 2017.

- ^ Hecht, Susanna B.; Cockburn, Alexander (2010). The Fate of the Forest: Developers, Destroyers, and Defenders of the Amazon, Updated Edition. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-02-263-2272-8.

- ^ Síntese de Indicadores Sociais 2000 (PDF) (in Portuguese). Manaus, Brazil: IBGE. 2000. ISBN 978-85-240-3919-5. Archived from the original on 14 June 2011. Retrieved 31 January 2009.

- ^ a b Hill, David (6 May 2014). «More than 400 dams planned for the Amazon and headwaters». The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 29 July 2017. Retrieved 18 July 2017.

- ^ Ellen Wohl, «The Amazon: Rivers of Blushing Dolphins» in A World of Rivers (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2011), 35.

- ^ a b Fraser, Barbara (19 April 2015). «Amazon Dams Keep the Lights On But Could Hurt Fish, Forests». National Geographic. Archived from the original on 29 July 2017. Retrieved 25 July 2017.

- ^ Ellen Wohl, «The Amazon: Rivers of Blushing Dolphins» in A World of Rivers (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2011), 279.

- ^ «Source of the Amazon River Identificated (Jacek Palkiewicz)». Palkiewicz.com. 19 November 1999. Archived from the original on 12 March 2007. Retrieved 13 February 2011.

- ^ Smith, Donald (21 December 2000). «Explorers Pinpoint Source of the Amazon (National Geographic News)». National Geographic. Archived from the original on 1 November 2017. Retrieved 15 July 2017.

- ^ a b «Studies from INPE indicate that the Amazon River is 140 km longer than the Nile». Brazilian National Institute for Space Research. Archived from the original on 11 April 2011. Retrieved 3 August 2010.

- ^ Contos, James (Rocky) (3 April 2014). «Redefining the Upper Amazon River». Geography Directions. Archived from the original on 12 March 2017. Retrieved 15 July 2017.

- ^ a b c Church 1911, p. 788.

- ^ Church 1911, pp. 788–89.

- ^ a b Guo, Rongxing (2006). Territorial Disputes and Resource Management: A Global Handbook. Nova. p. 44. ISBN 978-1-60021-445-5. Archived from the original on 15 October 2015.

- ^ «Amazon (river)» (2007 ed.). Microsoft Encarta Online Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on 6 March 2008. Retrieved 12 August 2007.

- ^ Roach, John (18 June 2007). «Amazon Longer Than Nile River, Scientists Say». National Geographic. Archived from the original on 15 August 2012. Retrieved 2 August 2017.

- ^ Church 1911, p. 784.

- ^ a b «Amazon River and Flooded Forests». World Wide Fund for Nature. Archived from the original on 12 March 2008. Retrieved 4 August 2010.

- ^ Molinier M; et al. (22 November 1993). «Hydrologie du Bassin de l’Amazone» (PDF) (in French). Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 October 2016. Retrieved 16 July 2017.

- ^ Junk, Wolfgang J. (1997). The Central Amazon Floodplain: Ecology of a Pulsing System. Springer. p. 44. ISBN 978-3-540-59276-1. Archived from the original on 8 September 2015.

- ^ Whitton, B.A. (1975). River Ecology. University of California Press. p. 462. ISBN 978-0-520-03016-9. Archived from the original on 15 September 2015.

- ^ Erickson, Jon (2014). Environmental Geology: Facing the Challenges of Our Changing Earth. Infobase Publishing. pp. 110–11. ISBN 9781438109633. Archived from the original on 8 February 2017. Retrieved 25 March 2016.

- ^ Lynch, David K. (1982). «Tidal Bores» (PDF). Scientific American. 247 (4): 146. Bibcode:1982SciAm.247d.146L. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican1082-146. Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 March 2016. Retrieved 25 March 2016.

- ^ «The Amazon Rainforest». Mongabay. Archived from the original on 27 August 2019. Retrieved 9 February 2020.

- ^ Figueiredo, J.; Hoorn, C.; van der Ven, P.; Soares, E. (2009). «Late Miocene onset of the Amazon River and the Amazon deep-sea fan: Evidence from the Foz do Amazonas Basin». Geology. 37 (7): 619–22. Bibcode:2009Geo….37..619F. doi:10.1130/g25567a.1. S2CID 70646688.

- ^ «Massive River Found Flowing Beneath the Amazon». Archived from the original on 10 November 2011. Retrieved 8 September 2011.

- ^ «Allpahuayo Mishana» (in Spanish). Servicio Nacional de Áreas Naturales Protegidas por el Estado. Archived from the original on 13 September 2016.

- ^ «Parque Nacional Natural Amacayacu» (in Spanish). Parques Nacionales Naturales de Colombia. Archived from the original on 2 February 2017.

- ^ «Parna da Amazônia». Instituto Socioambiental (ISA). Archived from the original on 30 October 2016.

- ^ «Parna de Anavilhanas». Instituto Socioambiental (ISA). Archived from the original on 6 May 2016.

- ^ World Bank (15 December 2005). «Brazilian Amazon rain forest fact sheet». Archived from the original on 3 May 2014. Retrieved 16 July 2017.

- ^ Albert, J. S.; Reis, R. E., eds. (2011). Historical Biogeography of Neotropical Freshwater Fishes. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- ^ «Amazon River Dolphin». Rainforest Alliance. Archived from the original on 1 March 2011. Retrieved 20 March 2011.

- ^ Cravalho, Michael A. (1999). «Shameless Creatures: an Ethnozoology of the Amazon River Dolphin». Ethnology. 38 (1): 47–58. doi:10.2307/3774086. JSTOR 3774086.

- ^ «Manatees: Facts About Sea Cows». Live Science. Archived from the original on 17 June 2018. Retrieved 17 June 2018.

- ^ Balliett, James Fargo (2014). Forests. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-47033-5.

- ^ «Giant otter videos, photos and facts – Pteronura brasiliensis». Arkive. Archived from the original on 7 January 2018. Retrieved 2 February 2018.

- ^ Cuvier’s smooth-fronted caiman (Paleosuchus palpebrosus) Archived 23 October 2017 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ James S. Albert; Roberto E. Reis (2011). Historical Biogeography of Neotropical Freshwater Fishes. University of California Press. p. 308. ISBN 978-0-520-26868-5. Archived from the original on 19 December 2011. Retrieved 28 June 2011.

- ^ Wohl, Ellen (2011). A World of Rivers: Environmental Change on Ten of the World’s Great Rivers. Chicago. p. 27. ISBN 978-0-226-90478-8.

- ^ Megafishes Project to Size Up Real «Loch Ness Monsters» Archived 3 September 2009 at the Wayback Machine. National Geographic.

- ^ «Candiru (fish)». Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Archived from the original on 18 July 2014. Retrieved 18 July 2014.

- ^ Wohl, Ellen (2011). A World of Rivers: Environmental Change on Ten of the World’s Great Rivers. Chicago. pp. 27–29. ISBN 978-0-226-90478-8.

- ^ Helfman, Gene S. (2007). Fish Conservation: A Guide to Understanding and Restoring Global Aquatic Biodiversity and Fishery Resources. Island Press. p. 31. ISBN 9781597267601. Archived from the original on 8 February 2017. Retrieved 28 March 2016.

- ^ «Bull Sharks, Carcharhinus leucus, In Coastal Estuaries | Center for Environmental Communication | Loyola University New Orleans». www.loyno.edu. Archived from the original on 4 August 2019. Retrieved 12 September 2019.

- ^ Ghai R, Rodriguez-Valera F, McMahon KD, et al. (2011). «Metagenomics of the water column in the pristine upper course of the Amazon river». PLOS ONE. 6 (8): e23785. Bibcode:2011PLoSO…623785G. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0023785. PMC 3158796. PMID 21915244.

- ^ Tom Sterling: Der Amazonas. Time-Life Bücher 1979, 8th German Printing, p. 20.

- ^ «Aguas Amazonicas».

- ^ «HyBam».

- ^ «Rivers Network».

- ^ «Secretaría do Meio Ambiente (SEMA)».

- ^ «Agência Nacional de Águas e Saneamento Básico (ANA)».

- ^ «Madeira (river)». Talktalk.co.uk. Archived from the original on 3 October 2012. Retrieved 13 February 2011.

- ^ «Purus River: Information from». Answers.com. Archived from the original on 28 June 2011. Retrieved 13 February 2011.

- ^ McKenna, Amy (9 February 2007). «Japurá River (river, South America)». Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 3 May 2015. Retrieved 16 July 2017.

- ^ Infoplease (2012). «Tocantins». Archived from the original on 3 August 2017. Retrieved 2 August 2017.

- ^ «Araguaia River (river, Brazil) – Encyclopædia Britannica». Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 29 June 2011. Retrieved 13 February 2011.

- ^ «Juruá River: Information from». Answers.com. Archived from the original on 28 June 2011. Retrieved 13 February 2011.

- ^ «Negro River: Information from». Answers.com. Archived from the original on 28 June 2011. Retrieved 13 February 2011.

- ^ «Tapajos River (river, Brazil) – Encyclopædia Britannica». Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 11 January 2011. Retrieved 13 February 2011.

- ^ «Xingu River». International Rivers. Archived from the original on 27 December 2010. Retrieved 13 February 2011.

- ^ «HowStuffWorks «The Ucayali River»«. Geography.howstuffworks.com. 30 March 2008. Archived from the original on 1 April 2012. Retrieved 13 February 2011.

- ^ «Guapore River (river, South America) – Encyclopædia Britannica». Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 29 June 2011. Retrieved 13 February 2011.

Bibliography[edit]

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Church, George Earl (1911). «Amazon». In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 1 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 783–90.

- Wohl, Ellen (2011). The Amazon: Rivers of Blushing Dolphins. A World of Rivers. The University of Chicago Press.

External links[edit]

- Information on the Amazon from Extreme Science

- A photographic journey up the Amazon River from its mouth to its source

- Amazon Alive: Light & Shadow documentary film about the Amazon river

- Amazon River Ecosystem

- Research on the influence of the Amazon River on the Atlantic Ocean at the University of Southern California

Geographic data related to Amazon River at OpenStreetMap

| Amazon River

Rio Amazonas |

|

|---|---|

Amazon River |

|

Amazon River and its drainage basin |

|

| Native name | Amazonas (Portuguese) |

| Location | |

| Country | Peru, Colombia, Brazil |

| City | Iquitos (Peru); Leticia (Colombia); Tabatinga (Brazil); Tefé (Brazil); Itacoatiara (Brazil) Parintins (Brazil); Óbidos (Brazil); Santarém (Brazil); Almeirim (Brazil); Macapá (Brazil); Manaus (Brazil) |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Source | Río Apurimac, Mismi Peak |

| • location | Arequipa Region, Peru |

| • coordinates | 15°31′04″S 71°41′37″W / 15.51778°S 71.69361°W |

| • elevation | 5,220 m (17,130 ft) |

| Mouth | Atlantic Ocean |

|

• location |

Brazil |

|

• coordinates |

0°42′28″N 50°5′22″W / 0.70778°N 50.08944°W[1] |

| Length | 6,500 km (4,000 mi)[n 1] |

| Basin size | 7,000,000 km2 (2,700,000 sq mi)[2] 6,743,000 km2 (2,603,000 sq mi)[5] |

| Width | |

| • minimum | 700 m (2,300 ft) (Upper Amazon); 1.5 km (0.93 mi) (Itacoatiara, Lower Amazon)[6] |

| • average | 3 km (1.9 mi) (Middle Amazon); 5 km (3.1 mi) (Lower Amazon)[6][7] |

| • maximum | 10 km (6.2 mi) to 14 km (8.7 mi) (Lower Amazon);[6][8] 340 km (210 mi) (estuary)[9] |

| Depth | |

| • average | 15 m (49 ft) to 45 m (148 ft) (Middle Amazon); 20 m (66 ft) to 50 m (160 ft) (Lower Amazon)[6] |

| • maximum | 150 m (490 ft) (Itacoatiara); 130 m (430 ft) (Óbidos)[6][7] |

| Discharge | |

| • location | Atlantic Ocean (near mouth) |

| • average | 215,000 m3/s (7,600,000 cu ft/s)–230,000 m3/s (8,100,000 cu ft/s)[10][11]

(Basin size: 5,956,000 km2 (2,300,000 sq mi)[12] 205,603.262 m3/s (7,260,810.7 cu ft/s)[13] (Basin size: 5,912,760.5 km2 (2,282,929.6 sq mi)[13] |

| • minimum | 180,000 m3/s (6,400,000 cu ft/s) |

| • maximum | 340,000 m3/s (12,000,000 cu ft/s) |

| Discharge | |

| • location | Amazon Delta, Amazon/Tocantins/Pará |

| • average | 230,000 m3/s (8,100,000 cu ft/s)[5] (Basin size: 6,743,000 km2 (2,603,000 sq mi)[5] to 7,000,000 km2 (2,700,000 sq mi)[2] |

| Discharge | |

| • location | Santarém |

| • average | 191,624.043 m3/s (6,767,139.2 cu ft/s)[13] |

| Discharge | |

| • location | Óbidos (800 km upstream of mouth — Basin size: 4,704,076 km2 (1,816,254 sq mi) |

| • average | 173,272.643 m3/s (6,119,065.6 cu ft/s)[13]

(Period of data: 1928-1996)176,177 m3/s (6,221,600 cu ft/s)[14] (Period of data: 01/01/1997-31/12/2015)178,193.9 m3/s (6,292,860 cu ft/s)[15] |

| • minimum | 75,602 m3/s (2,669,900 cu ft/s)[14] |

| • maximum | 306,317 m3/s (10,817,500 cu ft/s)[14] |

| Discharge | |

| • location | Manacapuru, Solimões (Basin size: 2,147,736 km2 (829,246 sq mi) |

| • average | (Period of data: 01/01/1997-31/12/2015) 105,720 m3/s (3,733,000 cu ft/s)[15] |

| Basin features | |

| Tributaries | |

| • left | Marañón, Nanay, Napo, Ampiyaçu, Japurá/Caquetá, Rio Negro/Guainía, Putumayo, Badajós, Manacapuru, Urubu, Uatumã, Nhamundá, Trombetas, Maicurú, Curuá, Paru, Jari |

| • right | Ucayali, Jandiatuba, Javary, Jutai, Juruá, Tefé, Coari, Purús, Madeira, Paraná do Ramos, Tapajós, Curuá-Una, Xingu, Pará, Tocantins, Acará, Guamá |

Topography of the Amazon River Basin

The Amazon River (, ; Spanish: Río Amazonas, Portuguese: Rio Amazonas) in South America is the largest river by discharge volume of water in the world, and the disputed longest river system in the world in comparison to the Nile.[2][16][n 2]

The headwaters of the Apurímac River on Nevado Mismi had been considered for nearly a century the Amazon basin’s most distant source, until a 2014 study found it to be the headwaters of the Mantaro River on the Cordillera Rumi Cruz in Peru.[21] The Mantaro and Apurímac rivers join, and with other tributaries form the Ucayali River, which in turn meets the Marañón River upstream of Iquitos, Peru, forming what countries other than Brazil consider to be the main stem of the Amazon. Brazilians call this section the Solimões River above its confluence with the Rio Negro[22] forming what Brazilians call the Amazon at the Meeting of Waters (Portuguese: Encontro das Águas) at Manaus, the largest city on the river.

The Amazon River has an average discharge of about 215,000 m3/s (7,600,000 cu ft/s)–230,000 m3/s (8,100,000 cu ft/s)—approximately 6,591 km3 (1,581 cu mi)– 7,570 km3 (1,820 cu mi) per year, greater than the next seven largest independent rivers combined. Two of the top ten rivers by discharge are tributaries of the Amazon river. The Amazon represents 20% of the global riverine discharge into oceans.[23] The Amazon basin is the largest drainage basin in the world, with an area of approximately 7,000,000 km2 (2,700,000 sq mi).[2] The portion of the river’s drainage basin in Brazil alone is larger than any other river’s basin. The Amazon enters Brazil with only one-fifth of the flow it finally discharges into the Atlantic Ocean, yet already has a greater flow at this point than the discharge of any other river.[24][25]

Etymology[edit]

The Amazon was initially known by Europeans as the Marañón, and the Peruvian part of the river is still known by that name today. It later became known as Rio Amazonas in Spanish and Portuguese.

The name Rio Amazonas was reportedly given after native warriors attacked a 16th-century expedition by Francisco de Orellana. The warriors were led by women, reminding de Orellana of the Amazon warriors, a tribe of women warriors related to Iranian Scythians and Sarmatians[26][27] mentioned in Greek mythology.

The word Amazon itself may be derived from the Iranian compound *ha-maz-an- «(one) fighting together»[28] or ethnonym *ha-mazan- «warriors», a word attested indirectly through a derivation, a denominal verb in Hesychius of Alexandria’s gloss «ἁμαζακάραν· πολεμεῖν. Πέρσαι» («hamazakaran: ‘to make war’ in Persian»), where it appears together with the Indo-Iranian root *kar- «make» (from which Sanskrit karma is also derived).[29]

Other scholars[who?] claim that the name is derived from the Tupi word amassona, meaning «boat destroyer»/[30]

History[edit]

Geological history[edit]

Recent geological studies suggest that for millions of years the Amazon River used to flow in the opposite direction — from east to west. Eventually the Andes Mountains formed, blocking its flow to the Pacific Ocean, and causing it to switch directions to its current mouth in the Atlantic Ocean.[31]

Pre-Columbian era[edit]

Old drawing (from 1879) of Arapaima fishing at the Amazon river.

During what many archaeologists called the formative stage, Amazonian societies were deeply involved in the emergence of South America’s highland agrarian systems. The trade with Andean civilizations in the terrains of the headwaters in the Andes formed an essential contribution to the social and religious development of higher-altitude civilizations like the Muisca and Incas. Early human settlements were typically based on low-lying hills or mounds.

Shell mounds were the earliest evidence of habitation; they represent piles of human refuse (waste) and are mainly dated between 7500 and 4000 years BC. They are associated with ceramic age cultures; no preceramic shell mounds have been documented so far by archaeologists.[32] Artificial earth platforms for entire villages are the second type of mounds. They are best represented by the Marajoara culture. Figurative mounds are the most recent types of occupation.

There is ample evidence that the areas surrounding the Amazon River were home to complex and large-scale indigenous societies, mainly chiefdoms who developed towns and cities.[33] Archaeologists estimate that by the time the Spanish conquistador De Orellana traveled across the Amazon in 1541, more than 3 million indigenous people lived around the Amazon.[34] These pre-Columbian settlements created highly developed civilizations. For instance, pre-Columbian indigenous people on the island of Marajó may have developed social stratification and supported a population of 100,000 people. To achieve this level of development, the indigenous inhabitants of the Amazon rainforest altered the forest’s ecology by selective cultivation and the use of fire. Scientists argue that by burning areas of the forest repeatedly, the indigenous people caused the soil to become richer in nutrients. This created dark soil areas known as terra preta de índio («Indian dark earth»).[35] Because of the terra preta, indigenous communities were able to make land fertile and thus sustainable for the large-scale agriculture needed to support their large populations and complex social structures. Further research has hypothesized that this practice began around 11,000 years ago. Some say that its effects on forest ecology and regional climate explain the otherwise inexplicable band of lower rainfall through the Amazon basin.[35]

Many indigenous tribes engaged in constant warfare. According to James S. Olson, «The Munduruku expansion (in the 18th century) dislocated and displaced the Kawahíb, breaking the tribe down into much smaller groups … [Munduruku] first came to the attention of Europeans in 1770 when they began a series of widespread attacks on Brazilian settlements along the Amazon River.»[36]

Arrival of Europeans[edit]

Amazon tributaries near Manaus